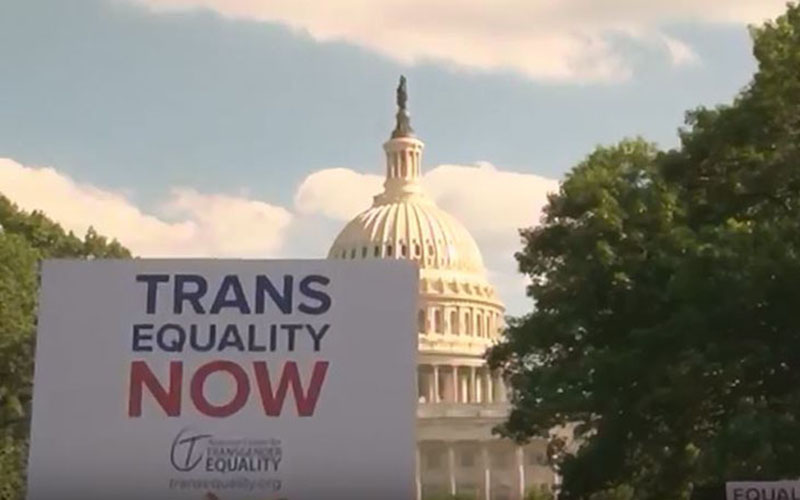

Advocates, including Jessica Girven and her 11-year-old daughter, Blue, who came out as transgender last year, rallied at the Capitol this summer against President Donald Trump’s proposed ban on transgender soldiers. (Photo by Megan Janetsky/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – Transgender individuals will be able to openly enlist, re-enlist and serve in the military without hiding who they are or being labeled by the military as mentally ill, beginning Jan. 1.

The change, which caps years of policy and court battles over transgender rights and the role of transgender individuals in the military, has been a long time coming, said advocates in Arizona. But while they welcomed the shift, they don’t think this is the end of their fight.

“Every time you get a win, it’s good for the home team,” said Stephanie Anne Donoghue, a volunteer in the Transgender Specialty Clinic at the Southern Arizona Veterans Administration Health Care System in Tucson. “Everybody sees it as a win, and we keep going for the wins.”

But she’s still cautious, “because I think there’s always that, you know, is something else going to change again and you’re back in the same boat?”

That caution comes from 18 months of back and forth between warring policies of the Obama and Trump administrations, and court rulings, the most recent of which came 10 days ago from a federal appeals court that rejected a government request to delay the changes.

“We’re a long ways away” from a final answer, said Abby Louise Jensen, vice president and general counsel for Southern Arizona Gender Alliance. She said that even if the issue ends up before the Supreme Court, a ruling would not come until 2019.

Transgender soldiers and veterans like Donoghue thought they won the fight more than a year ago when the Defense Department under President Barack Obama announced a policy opening military service to transgender individuals. That policy, announced on June 30, 2016, was to be phased in over the next year.

But on June 30, 2017, the eve of full implementation, current Defense Secretary James Mattis announced a six-month delay in accession – or enlistment – of transgender individuals. That was followed weeks later by President Donald Trump’s surprise tweet overturning the Obama-era policy entirely.

“After consultation with my Generals and military experts, please be advised that the United States Government will not accept or allow… Transgender individuals to serve in any capacity in the U.S. Military,” his three-part July 26 tweet said. “Our military must be focused on decisive and overwhelming…victory and cannot be burdened with the tremendous medical costs and disruption that transgender in the military would entail. Thank you.”

After consultation with my Generals and military experts, please be advised that the United States Government will not accept or allow……

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 26, 2017

Donoghue said that when some of the people she worked with heard the news, “it was like they just got kicked in the gut.”

Steve Kilar, spokesman for the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona, said the group was “shocked … by the very cavalier announcement of the ban by President Trump.” Erin Russ, director of programs for the Southern Arizona Gender Alliance, said Trump’s justifications for the change were “ludicrous” and called it “very obvious that this was a political move at the expense of the military.”

The move was attacked from both sides of the aisle on Capitol Hill, with Sen. John McCain, R-Arizona, saying that “any American who wants to serve our country and is able to meet the standards should be able to do so – and should be treated as the patriots they are.”

But others, like Rep. Vicky Hartzler, R-Missouri, hailed Trump’s move. Hartzler had backed an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act to stop the military from funding gender reassignment surgery, but the proposal failed.

“I believe the president rightly decided to go back to the earlier policy,” she said in September. “And so I was glad that he decided to make that move, to make sure that every defense dollar goes to where it’s needed.”

In August, the White House formally directed the Pentagon to ban transgender people from enlisting and gave Mattis six months to develop rules for transgender military personnel already serving. Mattis followed with interim guidance and promised to deliver a plan on transgender policies by February that would “promote military readiness, lethality, and unit cohesion.”

By that time, several lawsuits challenged Trump’s reversal and in October, U.S. District Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly blocked the Pentagon’s delay, agreeing with opponents that the administration’s reasons for reversing the Obama policies were “hypothetical and extremely overbroad.”

A RAND Corp. study, cited by the Obama administration in its policy decision, found that if transgender soldiers were allowed to serve, “the number would likely be a small fraction of the total force and have minimal impact on readiness and health care costs.”

Transgender people are twice as likely to serve as the general population, according to a 2014 Williams Institute survey, but the lead author of the RAND study said it’s important to keep the numbers in context.

“We’re talking about one-tenth to five-tenths of a percent of the active component, and the same in the selected Reserve,” said Agnes Gereben Schaefer, lead political scientist at RAND.

Advocates welcomed the court victory that allows transgender individuals to enlist in the military for now. But they said they expect the fight to continue. (Photo by Emma Lockhart/Cronkite News)

Even if the maximum number of transgender active/reserve personnel neared 11,000, as the RAND study said, a smaller number of them would seek further medical aid to transition.

“We’re talking about very small numbers,” she said.

Russ’ own experience is one reason she disagrees with the administration’s reasoning to ban transgender people from serving openly.

“Most of the transgender people I know, once they come to live their lives authentically, they don’t have the same issues they did before,” she said.

Russ said that before the Obama administration change in policy, being transgender was considered a mental illness to be specified on enlistment documents. But Russ, who was still living as a man when she enlisted, “thought I was fine … I didn’t think I had any mental illness issues.”

She served in the Army from 1979 to 1990, when she said she was forced to resign her commission after her superiors found out she was transgender.

“As an infantry captain, the Army felt it would be just easier for me to resign and disappear than than to try to make a big stink about things,” she said.

It took Russ 10 years to decide to transition.

“I didn’t want to be transgender,” she said. “I spent that 10 years doing everything I could to not be who I am. And it was emotionally very strenuous. And in the process, I became depressed.”

Besides being forced to quit the military, she said she got divorced, lost contact with her children and couldn’t find another job. She decided to transition after she tried everything else. And that was the fix she was looking for.

“Once I become comfortable with who I was, I became much more productive,” Russ said.

Donoghue volunteers at the Tucson VA clinic where a team of medical and mental health professionals evaluate and assist transgender individuals – both veterans and active military personnel – through transition. She said that, as of October, 168 transgender veterans had come to the clinic, which supports 35 other VA facilities.

Donoghue helps in the process of legally changing names and genders, assisting with the necessary paperwork and petitions. She’s also there for moral support.

Stephanie Donoghue, who volunteers to help transgender veterans at a cliniic at the Tucson VA, said her clients felt like they got “kicked in the gut” when President Trump said he would ban transgender soldiers. (Photo courtesy Stephanie Donoghue)

“A lot of it, I think, is being able to listen to them,” she said. “Giving them someone to talk to who’s been there, who’s not going to be looking at them like, ‘Oh, God, what a nut.'”

Donoghue isn’t a licensed professional, although she said “a lot of people treat me as an expert” on transgender issues. And for good reason: She is a veteran and transgender woman herself.

Donoghue knew something was wrong as early as her third birthday, but didn’t understand it until her body began to change more than 50 years later. It was then that she learned she was born intersex, which is a person with either both male and female reproductive parts or ambiguous genitalia.

Her parents decided to raise her as a boy, she said, because they already had two girls. She was not told about the circumstances of her birth and gender assignment. She remembers taking “vitamins” that turned out to be testosterone and other supplements to help her grow up to be a “healthy young man.”

Donoghue said she grew up with a lot of confusion and anger, and was withdrawn as a kid. She took a lot of that anger out on the walls of the family’s shed, she said.

At age 19, with a wife and a baby, she enlisted in the Air Force, where she thrived.

But then, after more than 50 years of living as a man, with two kids and a solid military career, Donoghue began noticing strange and gradual changes. Her breasts grew and her mood became unpredictable – she cried at the littlest things. She went to the doctor and, after an ultrasound, was told she was in the throes of female puberty.

Her body’s changes forced her to make a decision, and Donoghue transitioned from a man to a woman. She said for the first time, she felt calm and relaxed in her own body.

“Every transgender goes to bed hoping they will wake up in the right body,” she said.

While courts have so far sided with transgender individuals, there is no guarantee it will last. The Pentagon last month issued rules for the interim, but made clear that it has not given up the court fight.

“As required by recent federal district court orders, the Department of Defense recently announced it will begin processing transgender applicants for military service on January 1, 2018,” the Dec. 11 guidance said. “This policy will be implemented while the Department of Justice appeals those court orders.”

Donoghue said she worries about what will happen to the transgender enlistee who ends up being first.

“My one concern is that they don’t become a subject of the media to the point where they just have trouble dealing with it all,” she said.

But ultimately, she said, “somebody’s got to be first.” Then added with a laugh, “But if they play their cards right, they probably will get a movie deal out of it.”

Russ said she knows a couple transgender people interested in enlisting, but not interested in talking to a reporter.

“A lot of our community are just wanting to live their lives and not have to be poster children or public advocates for being treated fairly,” she said.