Volunteers sort through returned audio materials at the Talking Book library in Phoenix. (Photo by Samantha Pouls/Cronkite News)

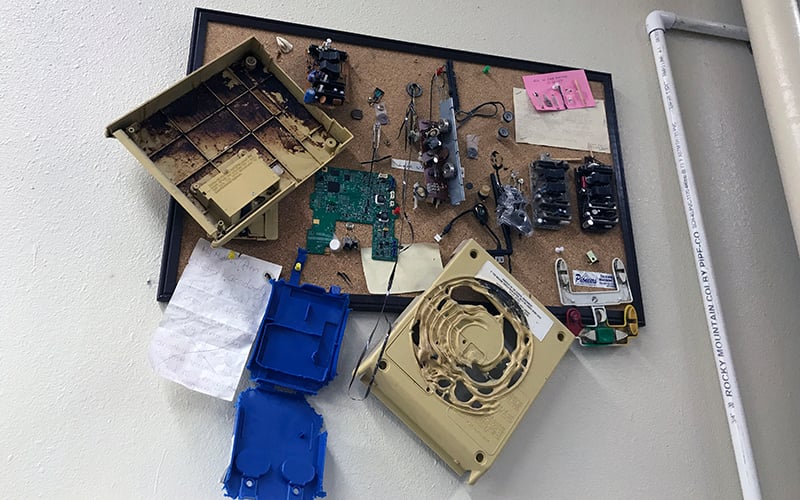

The Talking Book library in Phoenix has a “wall of shame” that displays audio players and cartridge cases that came back to the library damaged. (Photo by Samantha Pouls/Cronkite News)

People return about 2,000 cartridges each day to the Talking Book library in Phoenix. (Phoenix Samantha Pouls/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Craig Turner opens one of many cardboard boxes that had just arrived at the Talking Book library early one October morning. He finds a surprise among them: A thank you note from a patron.

He opens another. This note says one of the library’s patrons has passed away.

“On a personal level, I love talking to these people,” said Turner, a machine services technician. “I love the notes. I keep them.”

In fact, handwritten notes fill Turner’s desk.

Those notes illustrate the personal connection the Arizona State Braille and Talking Book Library has with its 9,000 patrons, who range in age from 4 to 106. It serves the visually impaired and physically limited community by providing materials in braille and in various audio formats.

The library provides each patron an audio player, and the patron can request audio books, magazines and videos, which include audio descriptions of the scenes. The library mails them cartridges containing flash drives they can use to listen to the materials from the audio player.

Although the library still handles physical materials – people return about 2,000 cartridges each day – patrons are increasingly turning to audio versions they can download directly from their own computers.

“The baby boomers are embracing the new technology and don’t even get the physical collection anymore,” said Christine Tuttle, the outreach librarian and special services supervisor.

Users can borrow and download new releases – such as books, magazines and newspapers – directly from the National Library Service’s website. The emphasis on digital has meant a decrease in the number of physical copies the Phoenix library produces.

“We have to see if there’s enough people asking for the material in order for it to become a physical copy,” Tuttle said.

Talking Book patron can request audio books, magazines and videos. The library, based in Phoenix, sends them in a cartridge containing a flash drive they can use to read books from the audio player. (Photo by Samantha Pouls/Cronkite News)

Still, the library has about 300 volunteers who do everything from sorting cartridges to recording new material in the library’s recording studios.

The basement houses the enormous collection of 150,000 titles, with numerous copies of each. The shelves look similar to those at other libraries, but the small blue boxes containing cartridges line these shelves.

Every state has a library for the blind and physically handicapped as part of the National Library Service. The Institute of Museums and Library Services funds Arizona’s Talking Book library, according to the Arizona State Library website.

Because users can access so many materials from the national system, the local office tries to focus on producing audio recordings of local materials, such as Arizona Highways magazine.

The library still updates its physical cartridge collection because “the generation before the baby boomers find the (digital) system daunting,” but it just makes fewer copies, Tuttle said.

Vicki Hodges, a volunteer and patron at the library, remembers a time when the Talking Book library distributed cassettes.

“With the digital, it has really opened up so many other topics and categories that weren’t previously available,” Hodges said.

She said it’s also more convenient.

“Right now, I have 180 books on my thumb drive,” Hodges said. “I copy these book onto my computer, that way, if I want to re-read a book, I can just copy it back onto my thumb drive, plug it back into the player and re-read it.”

The players are about the size of medium book. The buttons are big so patrons can easily use the volume, play, stop, tone and speed functions. The players also can withstand most wear and tear.

“I’ve thrown this through the sandbox, then through the washer and dryer,” Tuttle said. “I’ve dropped it from a 20-foot ladder. I’ve taken it on international flights, and there’s been no trouble whatsoever.”

That doesn’t mean the players are indestructible. The library has a “wall of shame” that features some of the worst incidents. There’s a player with Cocoa Puffs stuck to it and a melted one as well.

Tuttle said anybody who can’t read standard print, hold a book or turn pages can qualify for the library’s service.

The program “gives the person the ability to participate in everyday life and conversation,” Hodges said.