GRAND CANYON – A spring used to rush through a hillside on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, nourishing bats, mule deer and other wildlife — that is, until bison trampled the watering hole into a mud puddle.

The herd has proven to be an environmental nuisance, depleting water sources, mowing down once-flourishing meadows to stubs of grass and wallowing in fields until they turn into dust bowls, wildlife experts say.

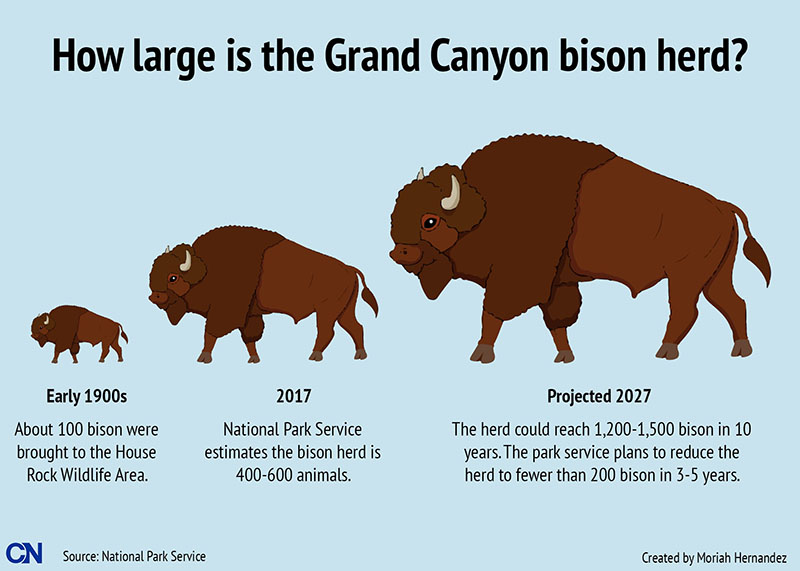

Officials for Grand Canyon National Park and other government agencies are considering lethal and nonlethal methods to reduce the 600-animal herd to around 200 within five years. However, those plans land at the controversial crossroads of salvaging the environment or salvaging the bison.

“We’re trying to find that happy balance where bison can be on the landscape and also have minimal impacts,” said wildlife biologist Brandon Holton.

If the herd goes untouched its numbers could nearly triple over the next decade, making the bison difficult to manage, experts say.

“We are already seeing pretty adverse impacts,” said Holton, who works for the Grand Canyon park service. “If we had 1,500 animals on the landscape here, it would be quite devastating.”

The bison rob other animals of resources they need to survive and basically overrun the landscape, disturbing the cycle of vegetation growth.

Part of the current plan for immediate herd reduction is to incorporate culling, or selective shooting, Holton said. Grand Canyon staff would oversee a group of licensed volunteer hunters who are capable of shooting the bison one at a time with extreme accuracy.

The bison meat would then be distributed among local tribes, the volunteers, and other groups, experts said.

Grand Canyon National Park and other government agencies like Arizona Game and Fish, the InterTribal Buffalo Council and others, view culling as a primary option for herd reduction. But some conservation groups, such as the Sierra Club, believe nonlethal methods of corralling and moving the herd should be exhausted before considering the alternative.

“I would hate to see the Kaibab National Forest and Grand Canyon National Park turned into a game farm for this species,” said Alicyn Gitlin, Grand Canyon program coordinator for the Sierra Club.

“The park is capable of getting these animals rounded up and getting them contained and transported in a humane manner. I would like to see that be the primary mechanism of moving these animals,” Gitlin said.

About four years ago a park service team did manage to round up and move 19 bison during a successful corralling attempt, Holton said.

He said a combination of culling and moving the herd is being considered, but plan details have yet to be determined.

Some of the bison would be moved back to their place of origin at House Rock Valley, just east of the park border. The bison, widely considered non-native to the North Rimlands they now occupy, were brought to the valley in the early 1900s to be bred with cattle as part of an experiment by a rancher known as Buffalo Jones.

The project was eventually abandoned after the hybrids didn’t prove valuable.

Poor containment of the herd, wildfires and a growing need for new food sources led the bison to eventually migrate to the Kaibab plateau. Grass and wetlands weren’t naturally developed for such large mammals in such large quantities, Holton said.

“Because these animals were brought here, there is no ecological niche for them in this region, so we really need to move them,” Gitlin said. “I think that would be a lot better destiny for these animals and a lot better destiny for these ecosystems that we treasure and that other wildlife depends on.”

Gitlin refuses to refer to the animals as “bison,” but instead calls them “bison hybrids” so people understand the species is non-native.

While groups disagree about prioritizing lethal versus nonlethal methods, those involved agree it has taken too long to settle on plans to reduce the herd.

“It’s the perfect story of letting things go too long,” Holton said.

When the bison first started migrating into the Grand Canyon National Park from House Rock Valley in the 1990s, the herd count was only about 100, Holton said.

Holton said herd growth was a matter of concern when he first started working for the park service nearly a decade ago.

“The decision made has been ten years in the making and everyone came to the conclusion that this initial herd reduction was the way to approach how to manage bison here,” said Emily Davis, spokeswoman for Grand Canyon National Park.

But Gitlin believes the current plan is not enough.

“This plan is very vague,” Gitlin said. “I would like a plan that’s more long-term and can be adaptable to what the conditions are in the future so the park can continue to control these animals and keep them out of the park.”