MESA – Visitors to antique shops on Main Street in Mesa will see stores crammed with primarily benign American memorabilia. A 19th century record player, a vintage 1990s Barbie, or a campaign button promoting Richard Nixon for president line the shelves.

Then, the eyes flit across something more startling. A set of spice jars in the shape of a Mammy, depicting a grinning, big-lipped, dark-skinned woman wearing a scarf.

The selling of African-American memorabilia in Arizona and elsewhere in the country sparks complex questions, similar to recent controversies over Confederate statues. Placing such imagery in the marketplace can raise the specter of racism, while also provoking thought that such products preserve history.

‘They’re meant to be cute’

Antique store owners selling Mammy figures and other African-American memorabilia in Mesa include a Jewish woman whose grandparents died in the Holocaust, an African-American woman who served in World War II and a man from a family of antique collectors who wants to save emblems of the past for future generations.

Michelle Holz, the owner of Michelle’s Antiques, said the spice jars she offered for sale are simply a part of history.

“It was made to be cute. It wasn’t made to be racist,” Holz said.

Holz, who is Jewish, said her family experienced discrimination — her grandparents died in the Holocaust.

A neighboring store owner once sold a photo of Hitler, she said. Although some people were upset, Holz was not offended. Selling such items, although controversial, is necessary, she said.

“When you erase this stuff, people have no knowledge where they came from,” Holz said.

Greg Farr, who is white, owns Antique Plaza in Mesa. He also sells what he called “black collectibles.”

Greg Farr owns Antique Plaza, a store in Mesa that sells many historical items. (Photo by Angelica Cabral/Cronkite News)

On a recent day, he had a Mammy cookie jar and figure in his store.

He said most of the people who buy them are African-American and the originals have become so popular, people are actually making reproductions to sell.

“To people who collect it, it’s not offensive. It’s just what it is,” Farr said.

Fannie McClendon is the 97-year-old owner of The Glass Urn, the store next door to Farr’s location. An African-American business owner, she said most of her customers who buy black memorabilia have been white.

She said she once had a woman come in and buy a black 19th century doll for her 7-year-old daughter.

“I think she wants to bring her up with the idea that just because (someone is) black, they’re not bad people,” McClendon said.

At times, she has been unsure whether to sell certain pieces. But she considers them a form of art.

“My husband and I loved art and in art you find all kinds of things,” McClendon said.

McClendon, known as Miss Fran to her friends, said serving in the Army alongside white military members and an interracial marriage in her family helped shape her views.

She added she is a lifetime honorary member of the Valley of the Sun Antique Dealers Association, an organization that treats her well.

Steeped in slavery

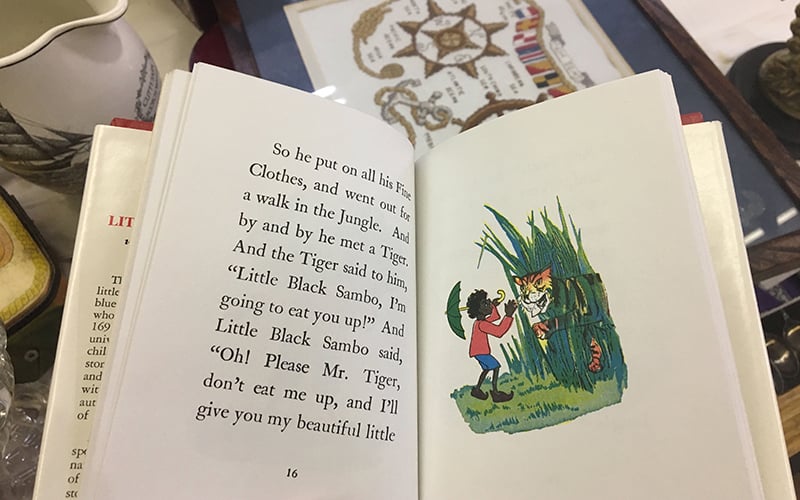

Black memorabilia items were first made centuries ago, as early at the 1200s, according to Collectors Weekly Magazine. Items at the time ranged from pottery to jewelry that depicted people from Africa. As Europeans and North Americans conducted the slave trade, the pieces gained in popularity and were often used as a way to reinforce stereotypes to bolster slavery.

After the Civil War ended, racist depictions were used to market and perpetuate the idea that black people were inferior, according to Collectors Weekly.

Everyday items like dishes and figurines portrayed the “Mammy,” a caricature of a motherlike black woman who loves to help the white family she works for, and the “Pickaninny,” a caricature of a raggedly looking, grinning black child.

Fannie McClendon runs The Glass Urn in Mesa. She sees black memorabilia as art. (Photo by Angelica Cabral/Cronkite News)

The complex issues surrounding black memorabilia extend to the people who buy such items. Historian Henry Louis Gates, the host of “Finding Your Roots” on PBS, is a collector, according to a 2015 post.

“We need to study these images in order to deflect the harm that they continue to inflict upon African-Americans, at the deepest levels of the American unconscious,” Gates wrote.

McClendon, the owner of the Glass Urn, said some black people come into her store and “turn their nose up” at the items. McClendon said she doesn’t fault them for disliking it.

“I think these are their thoughts, I don’t know what they went through in life,” McClendon said. “A lot of people went through an awful lot of things, in the South especially.”

Artifacts that educate

The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, at Ferris State University in Michigan, opened five years ago to document such relics, according to its website.

It has more than 9,000 pieces and is intended to serve as a teaching tool.

“The only real value of the museum has ever been to really engage people in a dialogue,” David Pilgrim, the museum’s founder, says on the site.

Donald Guillory, a history professor at Arizona State University, said he sees black memorabilia as a way to talk about how people have been misrepresented and to look at a period of time he doesn’t want to repeat. But, as an African-American, he has mixed feelings.

“I’m conflicted because I see them both as a historian and as an African-American,” Guillory said. “For me, as a historian, I like seeing them in the appropriate context and I think that’s what a lot of people have missed.”

He said if someone is collecting African-American memorabilia, he would want to ask them why they chose to do so, just as with any other collection.

“If it’s anything other than learning the context or teaching about it, why would you want something that offensive, or that overtly offensive, in your home?” Guillory said.

In terms of modern day caricatures, Guillory has issues with hip-hop and trap music. While he feels it has its place, he thinks people can see it and misunderstand what African-American people are really like.

“People on the outside of that may start to accept that as the norm or representative of the culture because they’re not as close or they don’t associate themselves with people that are part of African-American culture,” he said.

He drew a distinction between the issue of removing Confederate statues and black memorabilia. Whereas people can use the antiques to learn, the statues play a different role because of the way society views memorials.

Memorials are “typically to honor something,” Guillory said. “They can easily be taken out of context, because if a statue is erected for somebody, we typically associate that statue being erected for good purposes.”

He said people can still learn about the Civil War era without the statues. In contrast, having pieces of black memorabilia can be valuable.

“You need those examples to show to people, as far as how things are misrepresented, how far we’ve come,” he said.