PHOENIX ‒ Dolores Huerta is a woman of many facets. Political activist, union leader, mother and a civil and women’s rights icon. She is also one of the most underrated public figures in recent history.

In her early 30s, Huerta was one of the first minority women to work as a lobbyist in the California legislature in the 1960s. In 1970 she and Cesar Chavez, a labor rights activist, negotiated the first union contract between farm workers and the farming industry in California. It came after five years of strikes, boycotts and tactics used to highlight precarious working conditions.

Now 87, Huerta still remains an active leader involved not only in labor issues but also in environmental, LGBTQ, health care and education issues. Through the organization she founded, the Dolores Huerta Foundation, she and others train community members to be politically active and organized.

“She’s an ongoing icon of struggle,” said Tupac Enrique, founder of the indigenous rights group Tonatierra, which originated from the farm worker movement of Huerta, Chavez and Arizona’s farm workers union leader Gustavo Gutierrez. “She is a barrier breaker, she made the connection between labor rights, women’s rights, children’s (rights) into and beyond the global fight for human rights.”

Yet Huerta has received less recognition than her male peers, even within the farm workers’ movement. When Chavez died in 1993, the executive board of the United Farm Workers, the union she co-founded with him, didn’t elect her to be his successor.

These and other aspects of her life are showcased in the documentary Dolores, which opened in Phoenix on Tuesday.

Since the beginning of her career, she never let the obstacles of being a minority in politics, both as a woman and a Latina, keep her from focusing on the main social and political issues at the time, as the documentary shows.

The 1960s was a decade of large social movements across the country. Between the opposition to the Vietnam war, civil rights movement, the feminist movement and the environmental activism, Huerta was influenced by the political climate of the time, which was pushing toward social and public policy changes.

“It was not so much about being a Latina woman as it was about what was happening during that period of time,” Huerta said in an interview with Cronkite News.

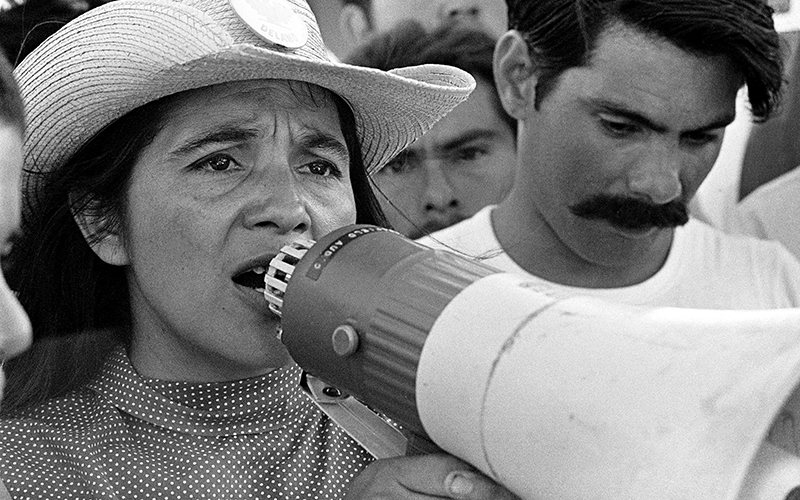

Dolores Huerta at a farm workers strike in Delano, California in 1966. (Photo by Jon Lewis, courtesy of LeRoy Chatfield)

To this day, Huerta stays focused on politics. Even during the Phoenix release of the documentary about her life, Huerta, who supported Hillary Clinton during her presidential campaign, wanted to center the conversation on how the community can be politically engaged and build an opposition to the current administration’s policies.

Huerta also has been a critic of Republican-led policies that she says have negatively affected Latinos and immigrants. In 2006, that position led her to coin the phrase “Republicans hate Latinos” during a speech to students in Tucson.

“The most discriminated people, the farm workers, were able to beat the president of the United States of America, Richard Nixon, the governor of California, Ronald Reagan and the most powerful organization of growers,” Huerta said during a Q&A session after the screening.

Huerta said she wanted Latinos in Arizona to remember that story as a lesson that political change is possible if they organize and vote in the 2018 midterm elections.

“We have to build our own wall. We’re going to build a wall in the U.S. Congress of good, progressive people,” she said.

Huerta specifically referred to President Donald Trump’s latest immigration proposals. Trump has said he would only support legislation to protect the DREAMers ‒ young undocumented immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children ‒ if it includes tougher immigration restrictions.

Huerta ended the session by chanting her iconic phrase “Si se puede,” which former President Barack Obama acknowledged was the inspiration for his campaign slogan “Yes we can” when he awarded her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012. It’s a phrase that Huerta said originated in Arizona in the early 1970s.

Though Huerta and Chavez looked for supporters in other parts of the country, they mainly focused on Texas and Arizona, where Chavez was born. But Huerta said Latino leaders in Arizona once told her a state law prohibited farm workers from organizing.

“You can’t do what you do in California here in Arizona. Arizona is a very different state. En Arizona no se puede (you can’t do that),” Huerta said they told her.

To which she replied, “Yes you can (si se puede).”

“For us here in Arizona, Dolores Huerta represents, in the present tense, not just in past memory, but in the present tense, the pillar of the farm worker movement,” said Enrique, who participated in the grape and lettuce boycotts in Yuma. He said she was “a constant inspiration for the struggle.”

Rafael Reyes, who went to the film screening with his family, is a teacher in Phoenix. But his parents were farm workers in San Luis and Yuma. He said he remembered handing out flyers outside of a grocery store that was selling pesticide-contaminated lettuce when he was a kid.

“(Dolores) is an example of struggle, of resistance, pride and passion of simply being ourselves, of rejecting humiliation, of being equal,” Reyes said in Spanish.

Dolores Huerta, a seasoned activist who co-founded the United Farm Workers union with Cesar Chavez, attended a screening of a documentary of “Dolores,” a documentary about her life’s work. (Photo by Courtney Mally/Cronkite News)