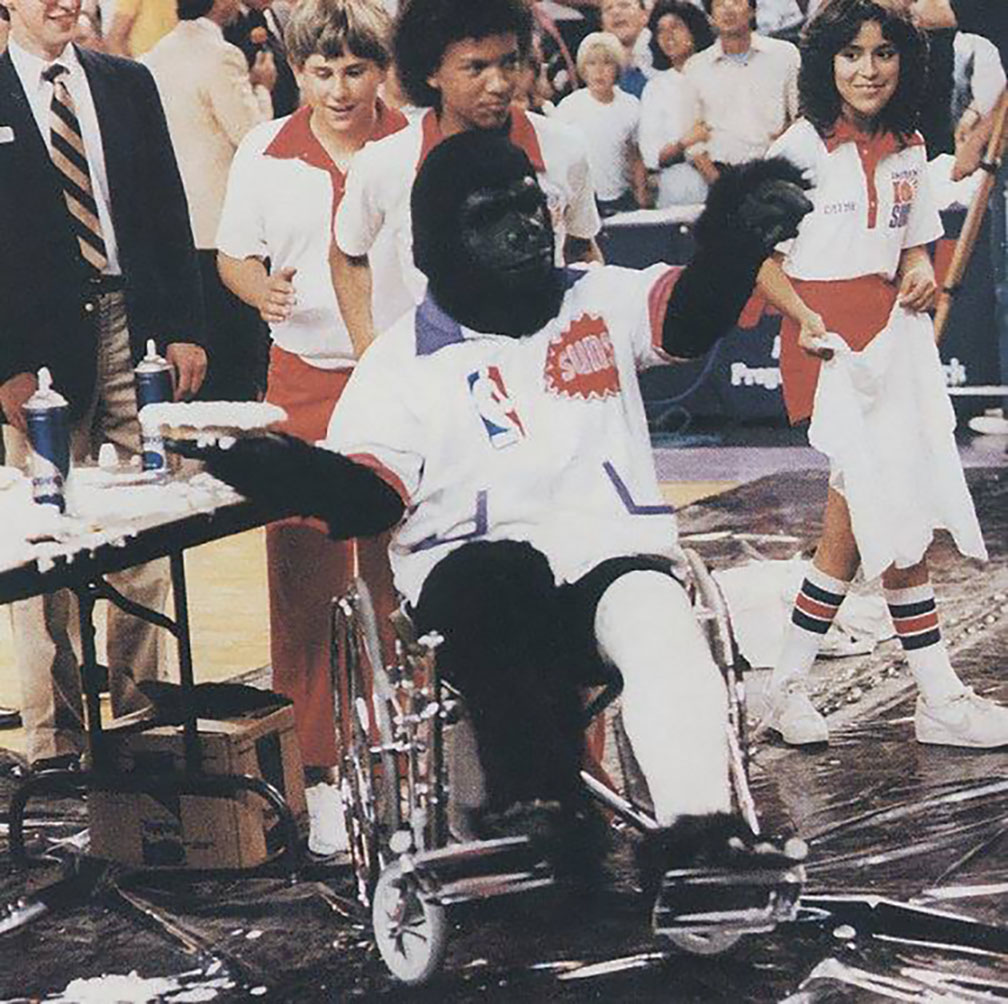

A young Ronnie Williams pushing Rojas, as the gorilla, in a wheelchair. Even injured, Rojas was determined to entertain the crowd. (Photo courtesy Ronnie Williams).

The Suns’ gorilla dances on court with NBA legends Isiah Thomas, Michael Jordan and Larry Bird (Photo courtesy Henry Rojas)

Rojas speaks to an employee orientation at Calvary Recovery Center. (Photo by Eric Newman/Cronkite News)

Henry Rojas left his job as the Suns’ gorilla for a life of insprational speaking and performing (Photo by Eric Newman/Cronkite News)

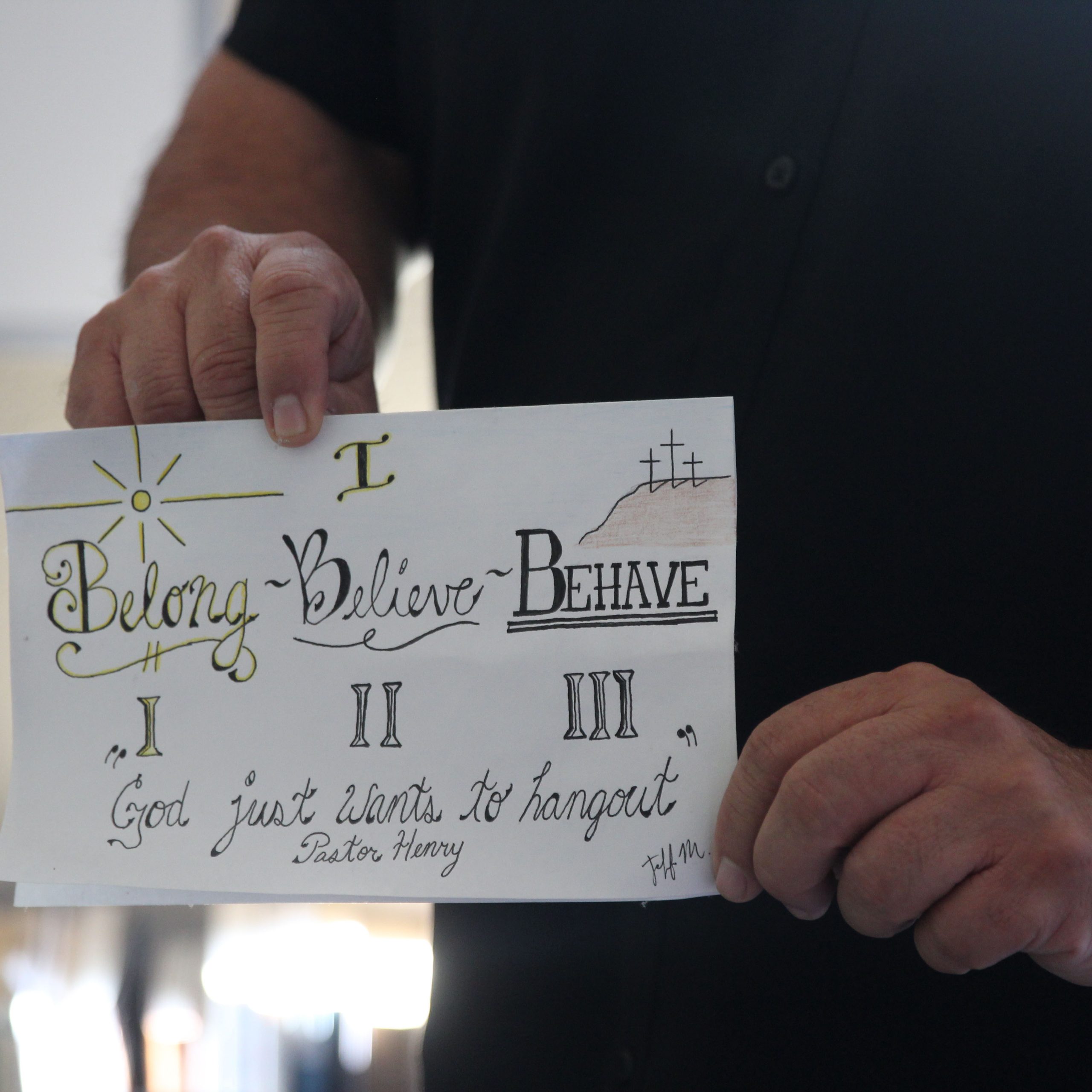

Henry Rojas once told someone that “God just wants to hang out with you.” The inspired person created a sign that Rojas keeps in his office. (Photo by Eric Newman/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX — In the 1980s, during halftimes, timeouts and other breaks in Phoenix Suns games, all eyes were on Henry Rojas, though much of the crowd did not know it.

The original Suns gorilla mascot, Rojas fell into the role in 1979 after working with the Eastern Onion Singing Telegram Service. On an assignment in which the client asked to have Rojas sing in a gorilla suit at a game, stadium cameras found Rojas running off the court in the suit, and with music playing, he “just started dancing.” He did not stop for nearly nine years.

These days, Rojas works as a chaplain and motivational speaker at Calvary Healing Center, a career path determined after learning something about himself while wearing the Gorilla costume.

Henry’s brother, Arthur Rojas, said that even from a young age, Henry was one of the most outgoing and funny people in the lives of everybody he met. He would sing, dance, mimic personalities of those he saw on television and joke about his surroundings and current events.

For a family that had its struggles, including the death of the brothers’ father at a young age, Henry essentially stepped into a family spokesperson role, speaking up for other members who had difficulties expressing their own personalities in the wake of sadness.

“He really was supportive without intending to be supportive because I was very withdrawn and quiet, he could be my voice in a lot of ways,” Arthur said.

Once his role as the Gorilla started, though, Suns fans could not get enough of him, or at least the gorilla.

Ronnie Williams, a Phoenix-area football coach who served as a ball boy for the team throughout Rojas’s tenure, was tasked with keeping up the quality of the suit, running to the locker room to get appropriate props and essentially assist Rojas in performances.

Williams remembered fondly a particular skit in which the Gorilla, clad in sequined gloves the pair had glued together before the game and a fedora over a tuxedo, would imitate Michael Jackson at the apex of the pop star’s career.

“The Moonwalk, his little dance and kicking the feet, it triggered a thing in the NBA where the players that were supposed to be paying attention in the huddles would be paying attention to the Gorilla doing the Michael Jackson skit,” Williams said. “I remember the NBA fining players because they weren’t paying attention to the coach in the huddle.”

The visiting locker rooms were adjacent to Henry’s dressing room, and Rojas said players would often barge in just to see the man behind the gorilla mask, and ask him what he had up his hairy sleeves that night.

“They were coming in my dressing room all the time, James Worthy and Magic (Johnson), and those guys, and asking me what bit I was going to do that night,” he said.

The timeout and halftime skits took a lot of energy, effort and planning, and good friend Art Brooks, currently the president and CEO of the Arizona Broadcasters Association, and with whom Rojas co-hosted a faith-based podcast called The Living Room, said Rojas would lose about 10 pounds a night just of water weight from the heat inside the costume. However, when he could make a crowd of 12,000 to 15,000 stand up and laugh, it all seemed worth it.

What people did not see was the pain on Rojas’s face every night, behind the mask crowds loved so dearly.

In 1989, Rojas walked away from fame and a high salary to pursue a career as a chaplain and motivational speaker, now at Calvary Healing Center in Phoenix.

His departure came as a shock to even some of the people closest to Rojas.

“We tend to be very humble people, and so for him to be behind the mask just seemed natural. And he could be out there, he could be the personality and be entertaining, and still be himself when he’s with us,” Arthur Rojas said. “Later on, when we found out how much of a struggle that really was, that was the strange part.”

As a loveable mascot, to which people would often share their most intimate, personal struggles, Rojas acted as a supporting figure.

However, Williams could see how much pain it caused Henry to not be able to respond, and how, unable to offer any advice or condolences, a smiling gorilla would hide a teary-eyed man holding himself back, due to his role, from completely being there for people in need.

“The only thing he could do was hug someone,” Williams said. “He couldn’t talk back to them, he could only hear their troubles and hear their pain through his ears and the gorilla mask.”

It was the inability to make the greatest possible difference in people’s lives that drove Rojas away, but the skills he developed as a communicator, as well as the desire to speak to people, suppressed by tape and a mask, were crucial in his current abilities as a speaker.

As the Gorilla, Rojas thought his childhood dream of becoming a professional speaker was delayed, if not over. However, the non-verbal cues that came from nearly a decade of dancing and visual communication, as well as the need to improvise in an environment that fosters chaos, were preparation for his current career.

“I found out that I was just as good a communicator at speaking as I was not speaking, doing the visual comedy,” he said. “The minute I have the energy in the room, or what the need is, or what’s going on, I can’t explain it, but I might have to change gears.”

As much as he desired to move on to a career in actively helping individuals, the transition was not seamless.

In one of his first-scheduled speaking engagements, Rojas agreed to talk to an audience at a Christian high school, in which the administration was interested in Henry’s faith and story as a mascot.

When it came time for the assembly, though, Rojas was nowhere to be found.

Later in the week, a letter came in the mail from Suns general manager Jerry Colangelo, which said the school had called him, frustrated that the staff had to fill somebody else in last-minute to speak to the excited students.

Rojas kept that letter on his refrigerator for years, motivating him to keep working, and not let fear get in the way of his dreams.

“I learned at that point that the very thing we want to do the most in life we are deathly afraid of when it comes our way,” he said.

While he had doubts about his path to making a living speaking, and while his costume did not allow Rojas to amass the type of following as “Henry Rojas” that he would have without the mask, those closest to Rojas could see his talent.

In a hectic work environment such as pre-game planning of skits in the locker room, Rojas always took at least a few minutes to try and help Williams get his own life straight. To this day, Williams calls Rojas a father-figure.

“When we could have been talking about the skits and the different things we were going to do, we were talking about school, talking about Ronnie Williams, and we were talking about how my day was every day,” Williams said.

That compassion for others has manifested itself in his speaking, as well as one-on-one sessions with people going through substance addiction or other debilitating mental health issues at Calvary. He will even pick up a guitar and sing songs, often made up on-the-spot, to try to encourage people to love themselves for who they really are.

Telling stories from his time in a suit, not showing his face, Rojas is able to relate to those who are trying to figure out how to establish their own lives, despite constant pressure to be somebody other than who they are.

“I think that is a metaphor for what I’m trying to do with audiences, is help them to understand the difference between their true self and their false self,” he said. “We all wear masks, and I literally wore one.”