Magan Carter holds her baby while his dad tries to make him smile. (Photo by Andrea Jaramillo Valencia/Cronkite News)

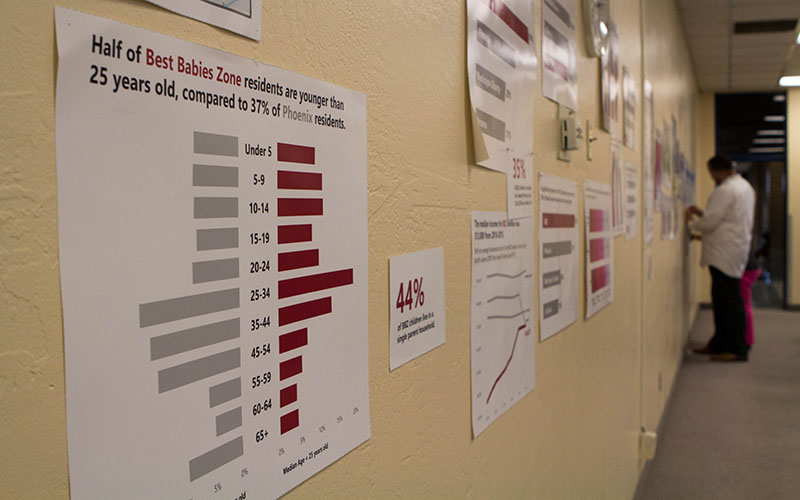

Posters with data about the Best Babies Zone in Phoenix are displayed on the wall at a town hall meeting hosted by South Phoenix Healthy Start on Sept. 20. (Photo by Andrea Jaramillo Valencia/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Immediately after Magan Carter’s baby was born, doctors put feeding tubes down his throat and hooked him up to an oxygen machine. He couldn’t breathe and had to use a feeding tube. Amari was in an incubator for three months.

Carter’s pregnancy lasted 26 weeks and four days. As an African-American woman, the odds were against her.

Across the United States, African-American women are more likely than any other race to give birth to premature babies, which is the leading cause of infant death for that population. Black babies are also more likely than other race to die before their first birthday. On average, Arizona has had higher infant mortality rates among African-Americans than the national rates from 2006 to 2014, according to data from the Arizona Department of Health Services.

Although the rates in Arizona have been decreasing from 2005 to 2015, the gap of infant mortality rates between African-Americans and whites hasn’t changed that much – it’s still fluctuating between two and three times as high. In 2015, 11 black babies died for every 1,000 births, while five white babies died for every 1,000 births.

Most of the African-American population in Arizona is concentrated in Maricopa County, specifically in Phoenix, where almost 40 percent live, according to census data. Maricopa County’s infant mortality rates decreased in 2014 and 2015 and were lower than the state rates, according to the Maricopa County Department of Public Health. However, AZDHS reports higher numbers. One county health official said that’s because the county excludes people who are not residents of Maricopa County.

Much of the research on health disparities has focused on understanding why African-Americans have higher infant mortality rates than other minorities who also experience similar economic, health and educational challenges.

In Arizona, African-American babies die at twice the rate of Latinos and 1.4 times more frequently than Native American babies, according to AZDHS.

Another enigma is why babies of African-American mothers with higher income and educational levels and healthier behavior than white mothers are still at a much higher risk of dying.

According to several public health and epidemiology researchers across the country, the reason is racism.

“If women who are African-American, who have great jobs, great education, live in safe neighborhoods, have access to insurance and medical care, and their babies are dying still at a higher rate, what does that say?” said Tatjiana Loncar, health educator with South Phoenix Healthy Start, a federal program dedicated to maternal and infant health.

Magan Carter holds her baby, who was in the NICU for three months. (Photo by Andrea Jaramillo Valencia/Cronkite News)

“If you take away all of that, what’s the difference?” she said.

Stress is one of the causes of premature births, and researchers have found that perceived or internalized racism – a direct result of the history of slavery and racism against the black population in this country – can be a stressor that disproportionately impacts African-American mothers.

Carter said she has experienced this kind of stress many times, particularly after moving from Memphis, Tennessee, a predominantly black city, to the Valley three years ago.

Once, she said she walked into a store to buy food and the owner asked her “When are you going to come work for me?” To which she responded, “I’m not much of a cook,” and he replied saying “I have dishes in the back.”

“A lot of people aren’t going to say that they have prejudice against you just because of how you look, but you can kind of feel it because of the different things that they do. It’s small, but it makes you feel unequal or inferior,” she said.

Carter was working as a manager at a pharmacy in Scottsdale before taking time off to take care of Amari. She lives with the father of her baby, who works as a bus driver, in an apartment in South Scottsdale, and she’s taking online audio production classes at the community college there because she wants to start her own business.

She said she’s had a few uncomfortable incidents in which she felt race was an issue. But Carter said she thinks she became more vulnerable to racism-related stress during her pregnancy.

She said she felt it when her doctor told her her symptoms were normal even though she was feeling very tired and dizzy most of the time. She felt it when the doctor gave her a hard time when she asked for a note to show at her job explaining her accommodations, such as eating snacks between meals. She said she felt it when one of her bosses told her she was “trying to go over the rules” for eating during work, even though she had a note from her doctor. She felt it again when he would reprimand her for taking a few minutes to sit down after feeling sick.

She said she felt it too when the nurses treated her differently than they did the other moms.

“If you’re in a hospital where it’s predominantly caucasian and you’re the only black person, and the only black baby in the whole NICU, you kind of can feel it a little bit,” Carter said. “I don’t know how to explain it because sometimes it’s not out there, it’s just like little, subtle hints, or conversations, and yeah, sometimes I did feel like I was excluded a lot. But at the same time, I want to give them the benefit of the doubt.”

Carter said she asked for a change of doctors because she felt hers wasn’t being supportive. She said she never knew her pregnancy was high risk until she had to go to the emergency room because her water broke 12 weeks before expected.

“(One) underlying principle of public health is that trauma is embodied, meaning that our families pass on the health ramifications of different traumas they’ve experienced,” said Sarah Barrett, program evaluator for South Phoenix Healthy Start. “That ties into the historical perspective of African-Americans in our country, from enslavement, to the civil rights movement, to where we are now.”

When Carter read a Facebook post about South Phoenix Healthy Start and infant mortality rates for African-American women, she couldn’t help but think of her own experience. She said she reached out to the organization because she wanted to learn more about breastfeeding, but also because she wants a support system in a place where she feels comfortable.

South Phoenix Healthy Start has been providing health services for infant care for the past 15 years in the south and west neighborhoods of the city, which are predominantly Latino and African-American and also have high infant mortality rates. This is their first year developing a new model to address infant mortality, inspired by the Best Babies Zone initiative, a program that began in California

Barrett said, they identified their area of focus by analyzing infant mortality, premature births and low birth weight rates in the 16 zip codes they serve. They found a census tract with the highest rates, which is from 19th Avenue to 7th Avenue, and from Southern Avenue and Baseline Road.

Now, they said their goal is to not only address the health disparities of low income, minority babies and moms of that area, but also the social and economic factors that contribute to better health outcomes.

One way they are doing this is by organizing town hall meetings to inform community members and leaders about infant mortality and to ask their input on how to best reduce infant mortality rates.

According to Rosalind Akins, member of South Phoenix Healthy Start, the subject of racism came up in their first meeting. Akins said some community members cried when they talked about the history of segregation in South Phoenix and how it impacts poverty, education and health.

“That’s why we’re trying to implement Best Babies Zones,” Akins said.

“(Best Babies Zone) says, let’s start figuring out a way of sustainability that’s natural and not a struggle. We’ve got to figure out ways to infiltrate and give them tools,” she said.

For Carter, learning about the numbers and statistics drove her to be as prepared as she can.

“It just really made me like, want to take more care of him (Amari), and make sure that he got the things that he needed. I watch over him a lot now,” she said.

CORRECTION: This article has been modified to reflect the Phoenix program is based on the Best Babies Zone initiative, but is not part of that program.