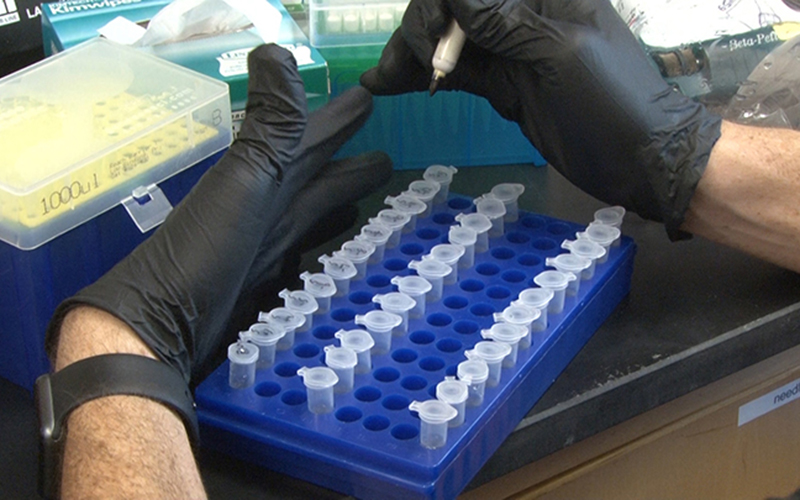

Daniel Powell, a postdoctoral fellow in immunobiology, works on a vaccine for Valley Fever in the Valley Fever Center for Excellence research lab in Tucson. (Photo by Blakely McHugh/Cronkite News)

In 2015, Arizona had 7,622 reported cases of Valley Fever, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Researchers at the University of Arizona say they’ve made progress in developing a vaccine. (Photo by Blakely McHugh/Cronkite News)

TUCSON – Researchers at the University of Arizona say they’ve made progress in developing a vaccine that could protect dogs from Valley Fever, a potentially deadly respiratory disease common in the Southwest.

The National Institutes of Health recently awarded the Valley Fever Center for Excellence a four-year, $4.8 million grant to speed up the development of the vaccine. The researchers hope that if they can perfect the vaccine, they may someday put it on the market for humans.

For now, they’re starting with smaller subjects.

Researchers injected mice with the live vaccine, and they found those vaccinated survived lethal doses of the infection compared to mice who weren’t vaccinated.

“We’ve waited up to six months. They don’t die. They actually don’t look sick at all,” said Dr. John Galgiani, director of Valley Fever Center for Excellence. “So it gives us confidence that this looks quite protective, and there’s really no reason to think that this wouldn’t also be protective in canines or humans.”

He said he believes getting a vaccine for dogs will serve as a stepping stone because obtaining approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for humans is much more difficult.

“If we can solve this problem for pet owners and for their dogs, that would add the momentum to have it move forward into humans as well,” Galgiani said.

Anivive Lifesciences Inc., a California-based biotechnology company, has licensed the vaccine and will help develop it, according to a news release.

Valley Fever comes from a fungus that grows in the dirt in certain regions, most commonly found in places such as the Sonoran Desert reaches.

“It’s a fungus in which when things get dry, small single cells of the fungus float off into the air, and if you inhale one of those spores,” he said. “That’s how an infection starts.”

He said two-thirds of the people exposed to the spore don’t actually see any symptoms of the disease. However, one-third can suffer from many symptoms.

“A small percentage of people have the infection not get stopped,” he said. “It continues to attack the lung, or in some cases, go through the bloodstream to other parts of the body and cause really widespread infection with tissue destruction in skin, bones and even the brain.”

In 2015, Arizona had 7,622 reported cases of Valley Fever, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The disease may affect even more dogs.

“It looks like pet owners and their dogs have just the same problem with this disease. In fact, it probably occurs in dogs about three times (as) frequently per year as it does in humans,” Galgiani said. “It’s really a significant problem, and it also requires the same sorts of treatments that we use for humans, and it can be just as devastating.”

There is no cure. Each year, Valley Fever kills more than 150 people, with a cost of half a billion dollars in health care and lost productivity, according to a University of Arizona news release citing CDC figures.

It’s also expensive for dogs.

“You give them medication for a year,” said Lisa Shubitz, a research specialist for the Valley Fever Center for Excellence. “In most cases, it can be much longer, including the rest of life of the dog.”

Medication can cost between $25 and several hundred dollars per month, depending on the dog’s size and treatment.

“It’s pretty expensive,” Shubitz said. “An owner can easily spend a thousand dollars just finding out their dog has Valley Fever before they spend anything on its treatment.”