PHOENIX – A conference room inside a stucco building in central Phoenix houses a combat zone.

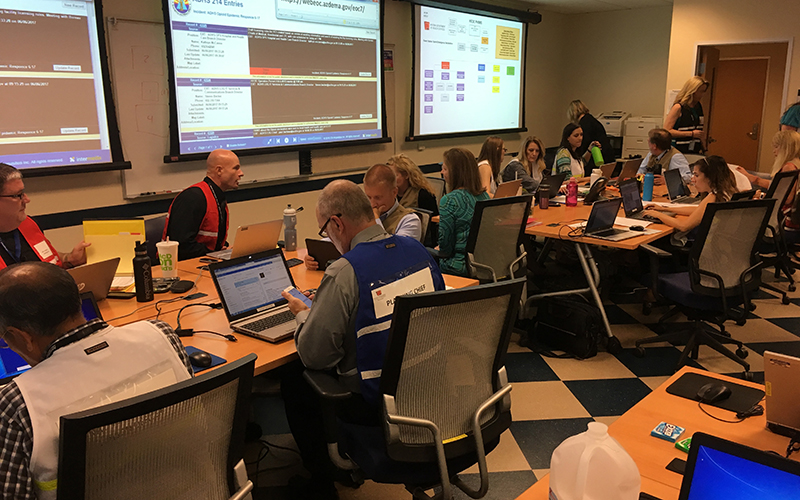

Men and women armed with laptops, video projectors and phones are packed at tables against a backdrop of vanilla walls working to battle Arizona’s relentless opioid crisis.

The decor in the operations center is office building bland. The consequences of failure are deadly.

Last year, 790 people died because of opioids, 16 percent higher than the previous year despite programs and other efforts to curb overdoses and other drug-related deaths, according to a 2016 report by the Arizona Department of Health Services. Other data is even more daunting: Deaths increased 74 percent over four years, the report says.

What may happen in 2017 is still unknown, but advocates for preventing and stopping opioid abuse say it’s clear the situation is urgent.

Gov. Doug Ducey on Monday declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency. Hours later the same day, the Arizona Department of Health Services opened a Health Emergency Operations Center. Its mission, government officials said, is to put a dent in the drug’s devastation of victims, families, the medical and health community, law enforcement and the state’s economy.

Goals include developing rules for opioid prescriptions and treatment, creating guidelines to educate health-care providers on properly prescribing the drugs, and providing training to law enforcement personnel on proper protocols for carrying and using naloxone.

“Currently, the center is focused on an enhanced surveillance advisory, emergency rule making, guidelines for prescribers, and training for law enforcement agencies and first responders who would issue naloxone, or Narcan, the opioid reversal drug,” DHS spokeswoman Holly Ward said in an email.

The center will remain open as long as needed, Ward said.

The Arizona Department of Health Services activated an operation center after Gov. Doug Ducey declared an opioid public health emergency. (Photo by Tyler Fingert/Cronkite News)

“We’re hoping to make an impact on it with some quick decisive action,” said Dr. Cara Christ, health-department director.

The governor’s emergency declaration is the first statewide public health emergency in at least a decade, according to DHS.

“Every situation has a focus. This one being opioids, is new, for us,” said Wendy Smith-Reeve, deputy director of the Arizona Department of Emergency and Military Affairs.

The declaration is to help coordinate public health efforts, free up resources and get access to better data.

The state health department has been looking at the opioid problem for a while, but without reliable data it has been difficult to track.

“We don’t have great data on opioid deaths,” Dr. Christ said. “Our opioid death data can lag a year behind and so we noticed in October we were still updating deaths that occurred in January.”

Officials are still collecting data on deaths from 2016, which could mean more deaths than have been reported.

Opioid addiction is a national crisis, spurring the Arizona health department to take a look at other states for best practices, Christ said.