TUCSON – Nearly 30 years ago, Calistro Manuel Mejias robbed a drug dealer, but something he didn’t expect happened. One of the men with Mejias choked the dealer to death.

The state charged Mejias with first-degree murder. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life in prison.

He was 15 years old.

Mejias’ sentence was overturned, and he ended up serving 20 years. He said he struggled to find work after leaving prison eight years ago because no one wanted to hire a convicted felon.

“Anytime I would have to check that little box,” he said. “Whether it (was applying) for a job or to apply for housing, as soon as I check that box, I already knew. There’ve been many interviews that I’ve sat in and slid my resume over and admitting that I’ve been imprisoned – showing what accomplishments I had in prison and whatnot – just had the resume slid right back to me.”

Today, Mejias helps disaffected youth in Tucson stay out of prison. When he heard about a move in the Legislature that could help other felons, he spoke in support of the measure in a YouTube video addressed to legislators.

Criminal justice reform is one of the few issues that has large bipartisan support in Arizona. Nearly everyone agrees that recidivism is a problem, and ex-offenders need support to overcome the stigma of prison to land a job. The problem is that not everyone agrees on the solution.

This divide is why reform has been incremental. The Arizona Legislature considered at least five reform bills this session, but only one made it into law.

One notable reform, which called for “banning the box” on job application forms, didn’t make it to the governor’s desk. However, one lawmaker vowed to bring back the effort next year.

What is ban the box?

Ban the box is a national campaign started by grassroots organization All of Us or None. The campaign’s goal is getting states to pass legislation that removes the felony check box on job applications so ex-offenders have a better chance at getting a job interview.

The idea is that employers first judge applicants by their qualifications and personality, said Beth Avery, a lawyer with the National Employment Law Project, a labor rights nonprofit.

But ban-the-box isn’t as literal as its name seems. It’s more like “moving the box,” which means employers could ask applicants if they have a felony and run a background check before they offer a job, said Brendan Mahoney, general counsel for HBI International, a private sector business that implemented a similar hiring policy more than 10 years ago.

“It’s been an unquestioned success in both directions,” Mahoney said. “We’ve given employees opportunities to get their life on track, make good wages … and, from the employer’s perspective, we’ve gotten very loyal, hard-working employees who appreciate that they have a job.”

HBI’s Phoenix warehouse has 52 employees, and one quarter of them are ex-offenders, Mahoney said.

The debate over ban the box

Currently, 25 states have passed ban-the-box legislation, according to a February report from the national employment project. Most states passed laws affecting some type of public employment. But nine states – Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island and Vermont – passed laws affecting private employers.

The efficacy of ban-the-box policies for a while went largely uncontested. However, recent studies suggest unintended consequences.

A study released in June 2016 found that although criminal records are a major employment barrier, ban-the-box policies “encourage statistical discrimination on the basis of race,” meaning that employers are relying on stereotypes instead.

The researchers tested how often companies called back applicants after ban-the-box policies were implemented. They submitted about 15,000 fake online job applications to employers in New York City and New Jersey.

The study found that racial disparities in callbacks increased 45 percent between whites and blacks. White call back rates increased while black call back rates stayed the same for companies compelled into a ban-the-box policy.

A separate study indicated that ban-the-box policies reduced employment chances by about 5 percent for young black men and nearly 3 percent for young Hispanic men without college degrees.

This suggests that employers are discriminating based on race and age, researcher Jennifer Doleac said.

“The evidence doesn’t support that ban the box works,” she said. “Get rid of it and replace it with something that works.”

Benjamin Hansen, who also worked on the second study, said their study had a surprising result: “If you increase the availability of criminal background checks, that leads to a net increase (in employment for whites and minorities).”

The employment project criticized both studies, questioning their methodologies.

“The core problem exposed by the studies is entrenched racism in the hiring process, which is expressed in the form of racial profiling of African Americans as ‘criminals.’ … When closely scrutinized, the new studies do not support the conclusion that ban-the-box policies are responsible for depressed hiring of African Americans,” according to a response posted in August 2016 on the group’s website.

“Ban-the-box helps with employment,” Avery said. “Let’s address racial bias among employers. … Getting rid of ban the box isn’t going to solve any of that.”

Doleac suggested an alternative to ban the box in which ex-offenders receive “employability certificates” that judges can issue if they determine an individual has been rehabilitated.

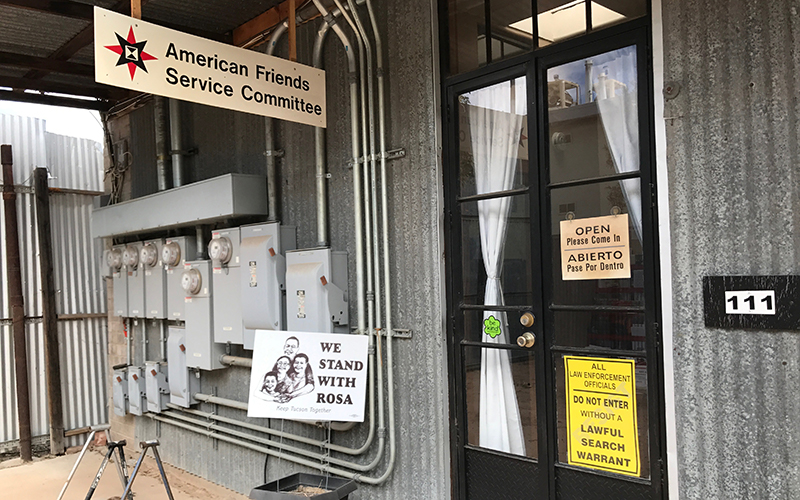

The Tucson office of the American Friends Service Committee, a national Quaker organization, drafted five bills addressing criminal justice reform, but only one made it to the governor’s desk. (Photo by Christopher Silavong/Cronkite News)

Criminal justice reform efforts stall in Legislature

The Tucson office of the American Friends Service Committee, a national Quaker organization, drafted five criminal justice reform bills this session, but only one made it to the governor’s desk.

Rebecca Fealk, a researcher for the organization, said the bills addressed the “collateral consequences” of incarceration by removing some employment barriers. When ex-offenders have jobs, their chances of re-offending drop significantly, she said.

But many of the bills died or changed so much they no longer addressed their original intent.

For example, Senate Bill 1071 addressed professional and occupational licensing and would have given state licensing boards the authority to issue provisional licenses to certain ex-offenders. So if an ex-offender wanted to work as a barber, he or she could obtain a probationary license as the first step toward a regular license.

However, lawmakers amended the bill to change the rules for inmates who violate community supervision after release from state prison.

Gov. Doug Ducey signed the bill into law in early May.

Lawmaker vows to bring back ban the box next year

Sen. Judy Burges, R-Sun City West, had introduced Senate Bill 1069, which turned into the “ban the box” bill, but it never made it to Ducey. Legislators debated whether the courts should destroy lower-class felony records or “set aside” felony offenses in some cases.

Sen. Martin Quezada, D-Phoenix, had introduced a “ban-the-box” amendment, also drafted by American Friends, which would have removed the felony check box on job applications at state agencies.

Burges said the House Judiciary Committee eventually killed ban-the-box in the end, and she will try again next year.

Mejias said he was disappointed.

“The goal is to create a community for those looking to leave their past behind,” he said. “The first thing you’re trying to do is survive (after leaving prison). You need to find a house. You need to find a job.

“Those are necessities that you need in order to live out here. … Getting a conviction set aside or expunged goes on the back burner because figuring out a way to eat and finding shelter is crucial.”