Norvelel Bufford sits outside the Justa Center in downtown Phoenix and waits for his friends. (Photo by Megan Bridgeman/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – It can happen in an instant: You lose your job. You can’t pay your medical bills. You have an accident.

For thousands of Arizonans, experts say it’s often one “catastrophic” event that forced them into homelessness. And there’s one growing section of the homeless population that’s especially hard hit – “older” people, generally ages 50 to 64.

This age group often slips through the cracks: They’re too young to qualify for most government safety net programs, and they may face increasing costs for housing and medical expenses.

One study indicated that in Maricopa County, the state’s most populous county, more than 50 percent of the homeless population is age 45 or older, according to the Department of Economic Security. That older homeless population increased by 34 percent from 2011 to 2014.

The study also noted that there’s an “upcoming surge” of people 62 and over who will “flood” resources.

One Phoenix-based nonprofit works to help address the unique needs of this growing population. The Justa Center, founded in 2006, exists exclusively for those aged 55 and older.

It provides everything from coffee and hot showers to assistance finding resources for safe housing and health care.

“It’s very disorienting to be homeless,” Executive Director Barbara Lewkowitz said. “It doesn’t matter why you’re homeless, it doesn’t matter what the underlying reason is. What matters is that you have the drive and the desire to make a difference in your life.”

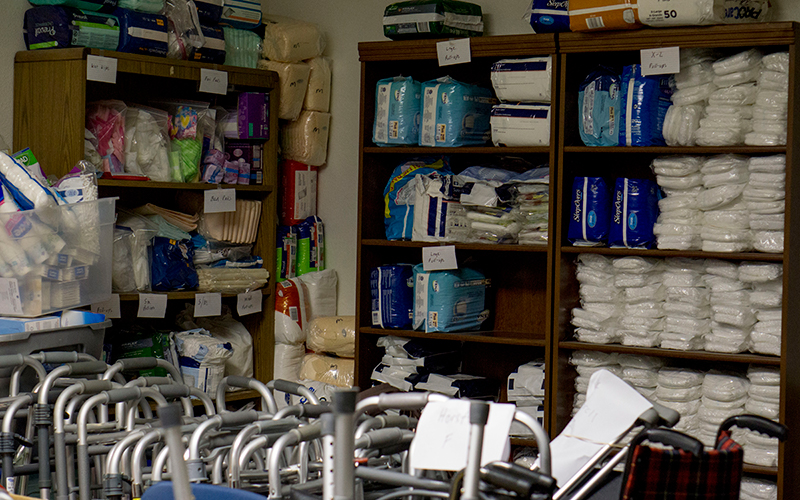

The nurse’s office at the Justa Center holds medical and accessibility products for its clients. (Photo by Megan Bridgeman/Cronkite News)

What is Justa Center?

About 130 people walk through Justa Center’s doors every day, according to its website.

The center’s end goal: Help find housing for those who need it.

It all starts with intake. Workers conduct an interview and provide a questionnaire to assess the needs of the individual seeking help.

Beyond supplying some basic needs, such as soap and toothpaste, the center provides resources such as a service counselor, a housing coordinator, a job coordinator, a nurse, a pastor and access to a veterans advocate.

“A common misconception is that we place people into homes,” said Nora Carrillo, a housing coordinator. The center workers can’t call up low-income housing and instantly get a person into a home.

“We can direct members where to go with applications or where to apply,” Carrillo said.

The average turnaround is three to four months. However, a person who has previous evictions and felonies can slow down the process.

Once they find housing, Justa Center provides a starter kit, which includes necessities such as coffee cups, plates and furniture.

Elizabeth Faiella, 57, said she found herself homeless after a move from Boston. She stayed with her daughter and son-in-law when she first came here, but she said she felt like a burden after five months.

She stayed in a women’s shelter while working a temporary job. She turned to Justa Center on her days off.

“When I finally got my apartment, they showed up with a whole truck full of furniture, a couch, a recliner, a kitchen table, a shower curtain, a can opener,” Faiella said.

About two years ago, the staff began noticing a problem with people who had gotten into a new home, but ended up homeless again.

To prevent repeating the cycle of homelessness, the staff created the Extended Care program. They now send ambassadors to check on clients to make sure they’re still housed and working, or if they need help.

“It could be something as simple as a shower curtain,” said Oly Cowles, the Extended Care coordinator. “(Or) it could be something as extensive as medical treatment, so we will make sure they have some sort of insurance to pay for that.”

The ambassadors take people to food banks or grocery stores with donated gift cards.

“For that reason, we have about a 93 percent rate of keeping people in housing,” Lewkowitz said.

Why is there such a need?

There’s a gap in benefits for many people in this age group.

For example, to qualify for subsidized housing, most places provide assistance for those 62 years and older, or 55 if the person has a disability.

Most people don’t qualify for Medicare or start receiving Social Security benefits until they hit 65, according to the National Coalition for the Homeless.

And even if they do get some assistance, it’s often not enough to cover expenses.

It doesn’t take much to push somebody into homelessness.

“There’s not any difference between a homeless person and us,” Lewkowitz said. “There could be one catastrophic event in their life, they can have a health problem, a car accident, a serious problem and lose their job, there’s no difference between me and the people that I serve here at Justa Center.”

Unless they store items at a shelter or a rental locker, many homeless people in Phoenix must carry all their belongings with them. (Photo by Megan Bridgeman/Cronkite News)

What’s the impact?

Left on the streets, these individuals age faster, requiring more medical attention and are at a higher risk of health issues, according to the National Coalition for the Homeless. Homelessness also takes an emotional toll.

They must transition from having a home, four walls and privacy to sleeping in crowded shelters.

Army veteran Chris Norwood, 60, found himself homeless after transferring from Georgia to Arizona. Since September, Norwood has been staying at the Central Arizona Shelter Services.

He said it’s not always safe for seniors on the street because they generally have some income or carry medication, which makes them a target for robbery. Norwood said he must get a motel on the first of the month because people know he will get a check.

Cowles agreed that seniors tend to become victims.

“They need the pain medications, so a lot of the younger folks know they have them, and they’ll beat them up and steal medications,” he said.

What’s ahead?

In the study by the Arizona Department of Economic Security, the author noted that “now is the time” to make changes to services and address the needs of this homeless population.

Those needs aren’t necessarily easy to address: They range from providing more affordable housing to addressing health care coverage gaps.

Cowles said those with mental health problems face additional challenges. People who have mental health issues may not get the treatment they need, may not want to act because of the stigma surrounding mental health, or they may not want to take their prescribed medication.

If Arizona could improve its mental health services, the population of homeless people would be smaller, Cowles said.

Justa Center can assist with mental health services, but its staff is small.

Justa Center operates solely off of private donations, gifts and small grants to run programs such as the Extended Care program.

“A lot of times, people come and drop off their donations,” said Terry Hinkle, a part-time staff member. “They’re generally affiliated with the church. A lot of donors are repeat donors.”

Because they operate primarily on donations, they often don’t have enough money for certain things, such as bus passes, Carillo said.

Many of the center’s staff work on more than their primary job title. “Getting more staff would also be helpful so the rest of us could really focus,” Carrillo said.