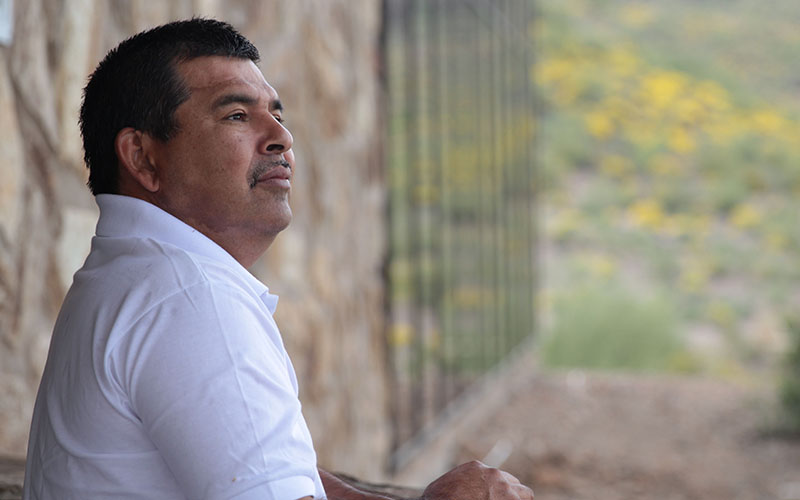

While Paz and Delgado wait to be granted U.S. citizenship, Shadow Rock United Church of Christ has offered them a place of sanctuary, which protects them from Immigration and Customs Enforcement. (Photo by Alyssa Hesketh/Cronkite News)

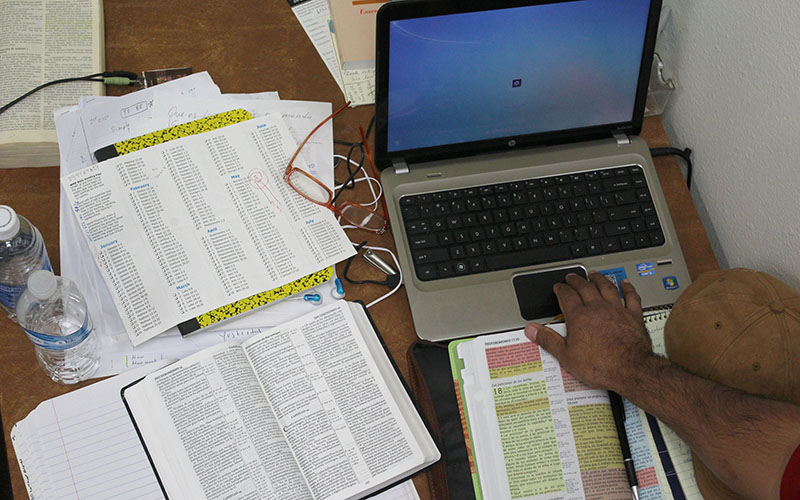

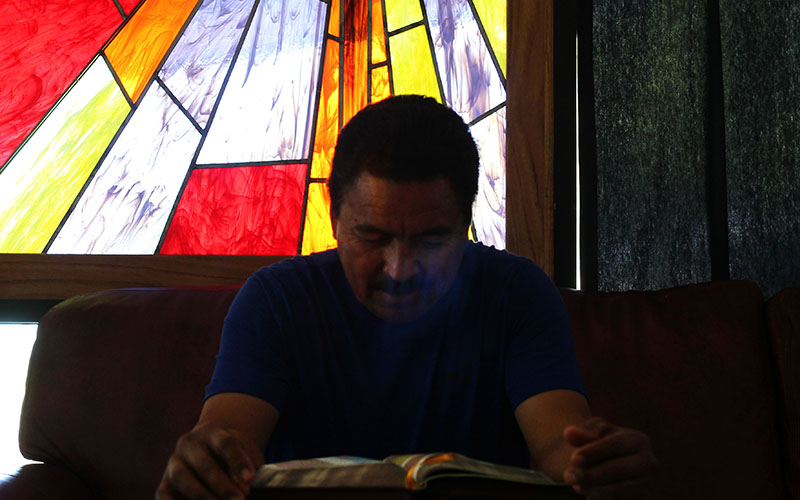

PHOENIX – A twin bed, a desk and a bookcase fill a small, rectangular room at Shadow Rock United Church of Christ in north Phoenix. On top of the desk, a Bible lays open, which Ismael Delgado, an immigrant from Mexico, uses each day to study scriptures.

Delgado has lived 1 ½ years in this room, off a hallway on the lower level of the church. He has lived more than a quarter century in Arizona but never as a U.S. citizen.

Here, he can escape the attention of U.S.Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and prays for comfort.

“Countless times I think ‘I’m leaving. I’m going home and let them come get me. However, we are close to God, close to Jesus Christ. Praying gives us strength,” Delgado said.

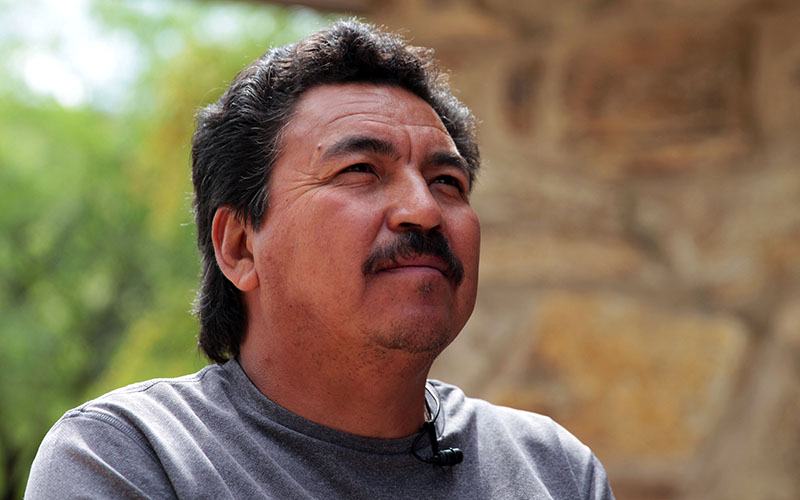

Down the hall, a larger room that is used by other members of the church for other activities during the day, also has served for ten months as a bedroom for Sixto Paz, an immigrant from Mexico who has been living in Arizona for 32 years without becoming a U.S. citizen.

The church is their sanctuary, considered a place of refuge or safety for undocumented immigrants. Technically, people like Paz and Delgado can still be arrested. But that it’s unlikely, with federal policies to avoid enforcement at “sensitive locations” except under certain circumstances, according to the ICE website.

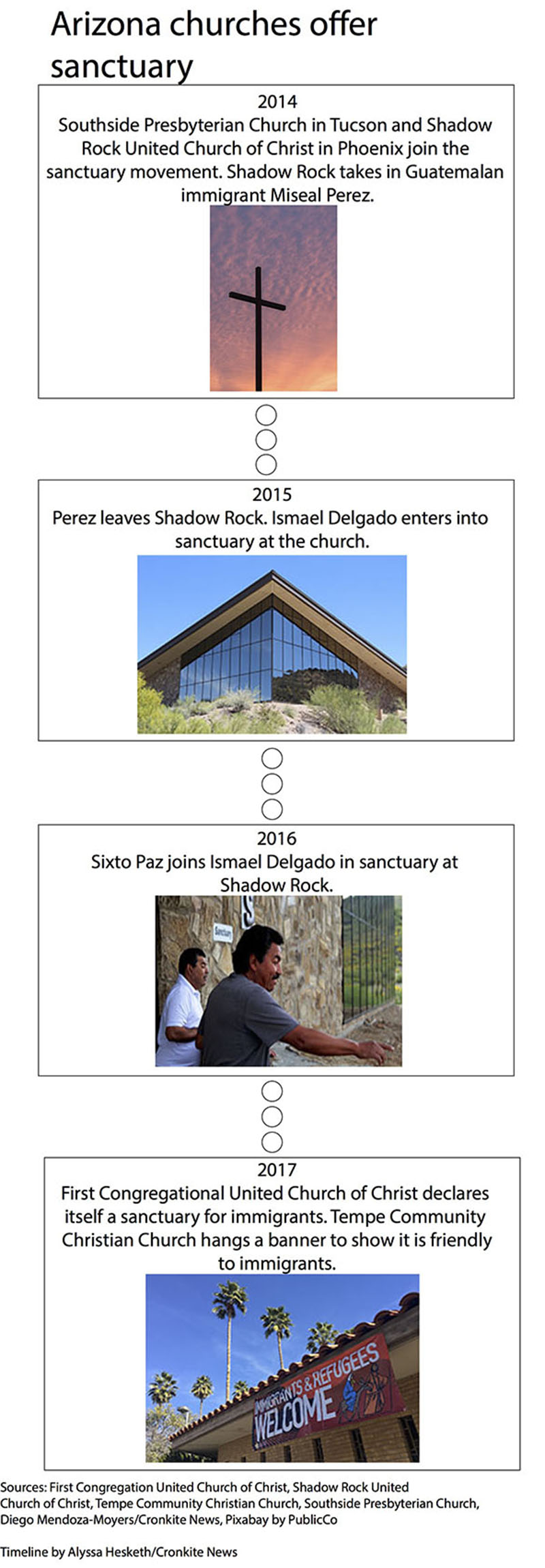

Since 2014, Shadow Rock has been part of the sanctuary movement, which involves more than 700 different churches and more than 4,000 people in the U.S. who help immigrants facing deportation because they are in the United States illegally. About four churches in Arizona offer sanctuary.

Churches offer sanctuary while immigrants are in the process of trying to gain U.S. citizenship. The movement in Arizona unofficially began in Tucson around three years ago.

But living in sanctuary has limits. Delgado and Paz can’t travel any further than the church parking lot. Delgado and Paz can’t visit family or friends, go to the grocery store, or to the movies. Friends visit them once a week, sharing coffee and conversation.

“Sometimes you can’t even sleep because you’re not working. You worry about your family, you worry because you left your job and your home. You left all those things behind,” Paz said.

Life before Shadow Rock

Until Shadow Rock, Delgado had worked as a cook in various restaurants, and Paz repaired roofs. Delgado lost his work permit because he committed a felony, which he would not disclose, and Paz was pulled over at an immigration checkpoint.

Both men wound up at Shadow Rock because their attorneys allowed them to seek sanctuary while they wait, hoping to become U.S. citizens.

Delgado can still be granted citizenship with a criminal record, as long as he did not commit a murder or an aggravated felony, according to U.S. immigration law. But President Donald Trump, who campaigned on a get-tough on immigration stance, has pledged to have undocumented immigrants who commit crimes deported.

Ken Heintzelman, the pastor at Shadow Rock, said Paz and Delgado’s transition into the church was easy, and members of the church are supportive.

Both men want to stay in Arizona – Paz wants to start his own roofing business, and Delgado wants to find another job as a cook or look for something new. For now, they wait for the government to decide whether to grant them the right to live and work in the United States.

Life at Shadow Rock

Their lives are confined to the church grounds, which includes a prayer garden, preschool, and basketball court. Their days are flanked by breakfast and bedtime, with a series of daytime routines in between:

Mondays and Tuesdays: Play pool, basketball or some other recreational activity. In the spring, Paz helped to repair the church’s roof. They study the Bible in the evenings.

Wednesdays: One of the busier days, as other churchgoers attend choir practice and prayer meetings.

Thursdays: Attend English language classes.

Fridays: Friends visit Paz and Delgado at the church.

Saturdays: Members of the sanctuary movement, on a conference call, discuss strategies to help immigrants.

Sundays: Church services are held.

That is their lives, repeated week after week.

Sometimes, Delgado and Cruz watch the news. Often, they talk. Delgado said Paz is good company. If not for him, Delgado may have given up long ago. They both said they are willing to wait as long as it takes to become citizens.

Sanctuary movement launches

When a church declares itself a sanctuary, a commitment is made to provide shelter and material goods for refugees.

The movement calls upon people of faith to stand in solidarity with immigrants and provide a safe place for those who face deportation. Those involved continue to ask other congregations for more resources and support for immigrants throughout the country.

In Arizona, First Congregational United Church of Christ in Phoenix, University Presbyterian Church in Tempe, and Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, provide sanctuary to undocumented immigrants. Community Christian Church in Tempe also welcomes immigrants.

In January, Southside Presbyterian announced that it would join “Sanctuary Rising,” a movement that involves 700 congregations protesting Trump’s immigration policies. The movement’s pledge states that those involved will help preserve human rights by opening up churches and communities to everyone, including immigrants.

Delgado and Paz said they know of sanctuary churches in Philadelphia, New York and Oregon. They feel that many people are unaware of the movement, and they would like more people to know about it so other immigrants who are in the same situation they are in can get help gaining citizenship.

Heintzelman said ICE does not take into consideration how much immigrants would be affected if they were deported after living in the United States for a long time.

“They have bought cars, they have bought homes, they have fallen in love, they have had kids. They really have built lives here, and whenever the implementation of immigration policy would divide those families, we did what we could to keep those families together,” Heintzelman said.

Before housing Paz and Delgado, Shadow Rock housed Miseal Perez, an immigrant from Guatemala who was fleeing violence in his country, for 110 days.

Heintzelman said Perez’s cousin was deported back to Guatemala and within four months, he had been abducted, tortured and murdered.

“If you feel like you and your family are facing violence, you are going to move to where there is not violence, and coming to the United States makes all the sense in the world to them,” said Heintzelman.

University Presbyterian Church in Tempe also provided sanctuary to Guatemalan-born Luis Lopez-Acabal, for around 100 days, according to the Rev. Eric Ledermann, the pastor. The church also works with Humane Borders to maintain clean water for people living along the Mexican border.

First Congregational United Church of Christ in Phoenix established Keep Phoenix Together, a free immigration clinic that provides help with covering citizenship applications and cost. Ledermann said the church will be taking in a female immigrant to provide her sanctuary.

The First Congregational church has also worked with ICE to temporarily house immigrants in private homes as they were being released from detention, which holds people suspected of visa violations, or illegal entry or unauthorized arrival in the United States. The church also provides food, water, formula, diapers, car seats and clean clothing for women being released from detention.

“We were also the first church in the Valley to officially say we are an immigrant welcoming community of faith, which means we welcome immigrants no matter where they are at on the journey,” said the Rev. James Pennington, church pastor.

“There is clearly a very strong Hispanic culture that is really celebrated, embraced and lived out here, and I love being part of the diversity of that culture,” Pennington said.

Pennington blames negative perceptions of immigrants on disinterest in people who look different than oneself. Heintzelman believes that people fear losing the power and privilege they may have and Ledermann believes people fear unfamiliar languages and culture. All three share the belief that their churches are simply helping people of God when they provide help or sanctuary to immigrants.

Immigration enforcement in the U.S.

Last year, the Department of Homeland Security apprehended 530,250 people nationwide and conducted 450,954 removals and returns, according to the ICE website. Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrested 114,434 people, and removed or returned 240,255 to their home countries, the website states.

“The agency does not define the term ‘sanctuary’,” ICE representative Yasmeen O’Keefe said in an email regarding whether or not sanctuary churches are legal under ICE policies.

Federal policies “are meant to ensure that ICE and (Customs) officers and agents exercise sound judgement when enforcing federal law at or focused on sensitive locations,” according to the website.

Trump wants to employ the federal government to find, arrest and deport those who are in the country illegally even if they have not committed a crime. He also plans to publicize crimes committed by undocumented immigrants and strip such immigrants of their privacy protection, erect new detention facilities, according to Homeland Security documents.

Cities and counties in 25 states and the District of Columbia have sanctuary laws aimed at protecting immigrants from deportation. California, Connecticut, New Mexico and Colorado have statewide sanctuary laws.

Arizona does not have sanctuary laws. Some community leaders tried to push Phoenix into being declared a sanctuary city but the Phoenix City Council voted against the request.

The Arizona Department of Public Safety has a policy that requires them to take action when they encounter undocumented immigrants.

“When a person is stopped for a traffic violation or contacted for another violation of law and the trooper observes indicators that the person is not in this country legally, the trooper is required to contact ICE,” DPS spokesperson Kameron Lee said in an email.

Paz and Delgado believe that Trump cannot handle all of the executive orders he plans to enforce, and are unsure of what lies ahead for immigrants. They feel safe at Shadow Rock and they are not afraid, and they said they what do whatever it takes to stay.

“What were going through here is not ordinary,” Delgado said. “It is a big deal. Something good is coming for us. Every bad storm has to come to an end, and at that moment is when we will see victory.”