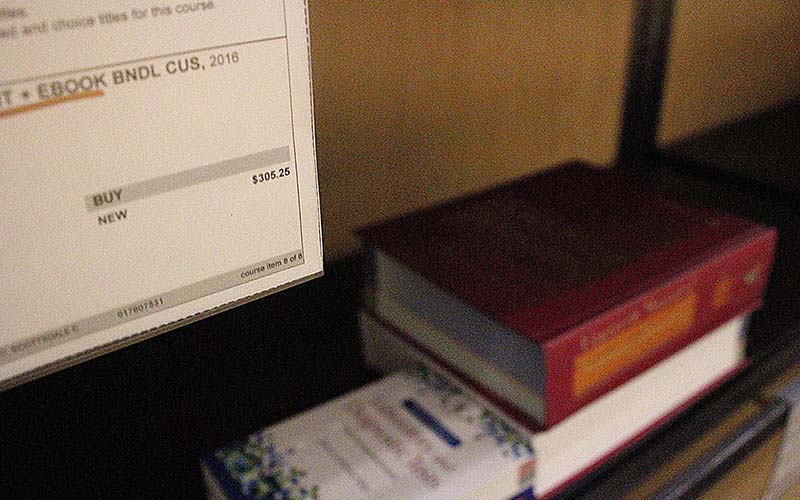

The price of a single textbook can easily reach $300 or more, and College Board puts the average annual cost of books and materials for students at $1,200. (Photo by Devon Cordell/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Tuition. Dorms. Parking. Supplies. The cost of higher education can seem daunting, but one Valley school wants to eliminate a large component of that high cost: textbooks.

The price of a textbook can easily reach $300 or more, and College Board puts the average annual cost of books and materials for students at $1,200. In response, Scottsdale Community College is integrating open educational resources into its courses with the intention of replacing textbooks entirely.

An open educational resource is content created and licensed in way that allows others to use it for free.

People share the content using one of six types of open licenses, the most common of which are through Creative Commons.

Teachers tap into that system to find a plethora of content. The system not only provides access to digital textbooks, but also course modules, lectures, games, quizzes and simulations. Educators also can create and share their own content using the open licenses, said Lisa Young, a faculty director at Scottsdale Community College

“We’re leveraging those (open educational resource) materials to eliminate the need for a textbook,” Young said.

Ninety-three percent of students do as well or better in their classes using open resources as opposed to traditional textbooks, according to the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, which advocates for the universal adoption of open resources.

The Maricopa Community College District’s Maricopa Millions OER Project has saved students like Marie Trinkus more than $9 million in education expenses over the 3 ½ years it’s been active, according to Lisa Young, a faculty director at Scottsdale Community College. (Photo by Devon Cordell/Cronkite News)

Teachers support the changes

Donna Slaughter, a math instructor at the college, said one of the most notable benefits of using open resources for her classes is the ability to update class materials quickly during the semester.

Slaughter said she designs her courses “based upon student feedback and feedback from other faculty using the materials.”

“We’re working to do a semester-by-semester implementation,” Young said.

Scottsdale Community College is gradually integrating the free resources into its classes.

With an original goal of saving students $5 million over the course of five years, the district’s Maricopa Millions OER Project has saved students more than $9 million in education expenses over the 3 ½ years it’s been active, according to Young.

“Instead of just purchasing something that is a finished product, what you’re doing is involving faculty in collaborating to create something that increases in value over time, because it’s adaptable,” said Matthew Bloom, an English professor at Scottsdale Community College.

Rising costs leave students with limited options

The high textbook prices leave many students unable or unwilling to purchase the books assigned for their classes, Young said. Many students attempt to complete a class without purchasing a textbook at all.

“Of course, it’s great to reduce the cost of education, but even more importantly, for our students to have access to the materials that we are assuming that they have access to,” Young said. “As an instructor, I’m assuming that students have knowledge that they don’t actually have.”

Sixty-five percent of students said they did not buy a textbook because it was too expensive, according to the Student Public Interest Research Group in a 2014 national study comprised of more than 2,000 students. The study also indicated that 94 percent of students who had foregone purchasing a textbook were concerned that doing so would hurt their grade.

“The tuition itself is very reasonable, but the textbooks were almost as much as the tuition,” said Carlene Winters, a student at Scottsdale Community College. She said she spent more than $1,000 on textbooks this year.

Since 2006, the cost of a college textbook increased by 73 percent, more than four times the rate of inflation. Overall, since 1977, the cost of textbooks has increased 1,041 percent, according to the same group in a 2016 study.

Caitlin Lindberg, a student and employee at the Scottsdale Community College bookstore said prices of textbooks can cost hundreds of dollars. (Photo by Devon Cordell/ Cronkite News)

Fewer choices often leads to higher prices

In a normal market for any product, competition between companies and consumer choice between products typically results in lower prices and higher quality.

However, in the textbook market, five major publishers – Cengage Learning, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, McGraw-Hill Education, Pearson Education and Scholastic – control most of the industry worth nearly $14 billion, according to an article from University Business.

In a news release by Cengage Learning, the company said it is integrating open educational resources into a curated program called MindTap ACE, which blends Cengage’s content with open resources.

“Far too often, the debate is an either/or of achievement versus price, when the reality is that (open educational resources) can complement proprietary content,” CEO Michael Hansen said in the release.

MindTap ACE is available as a pilot program for five courses, and the product’s pricing starts at $40, according to the release. It doesn’t mention how high the prices can go from there.

“It’s not about the cheapest options, it’s about the best options,” said Peter Cohen, executive vice president of McGraw-Hill Education. “If they get the best resource at the most affordable price possible, that’s the best option.”

Cohen said the reason textbook prices can get as high as they do is because of the supply chain it takes to create the book – paying for copyrighted photos, the research and development, the authors, and the actual producers, among other things.

“The concept of open educational resources co-existing with public resources is something that we believe in, we’re very comfortable with and we support, ” Cohen said.

Eighty-two percent of the more than of 2,000 university students surveyed in a national poll said they would do significantly better in a course if the textbook was available free online and buying a hard copy was optional, according to a report by U.S. Public Interest Research Group released in 2014. (Photo by Devon Cordell/Cronkite News)

Instructors: Open sourcing does have challenges

“How a resource is licensed has nothing to do with its quality,” Bloom said.

Bloom said he has a lot of material to choose from to use for his English classes, but instructors may face challenges finding exactly what they need.

“The hardest part is finding the right materials that are usable and putting the course together,” Bloom said. “It’s a lot easier to just tell your students to buy a textbook than it is for you to arrange (open educational resources) into a course. It takes a little bit of extra work.”

But once an instructor has assembled the course, other teachers can use those same materials for their own classes, Bloom said.

“As long as we are provided the materials we need to be successful in the course, I’d definitely go with that option,” said Audrey Wong, a Scottsdale Community College student.

Scottsdale instructor says variety increases student engagement

Some Arizona schools have begun to make open resource options available to students, but Scottsdale Community College is the first to explicitly begin replacing the textbook for courses entirely, according to the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition.

“A lot of people are using (open educational resources) to supplement a textbook, but it can be replaced,” Bloom said. “Why would I make my students buy a textbook when you can get everything for free online? And it’s not only legal for them to access the content, but you can actually have them do more interactive things.”

By providing a variety of resources, Bloom said he has seen a higher overall engagement from his students.

Eighty-two percent of the more than of 2,000 university students surveyed in a national poll said they would do significantly better in a course if the textbook was available free online and buying a hard copy was optional, according to a report by U.S. Public Interest Research Group released in 2014.

“There isn’t actually a cost (to the school) for the free textbooks, the cost is actually faculty time to go out and find these materials that other people have been willing to create and share,” Young said.

Other U.S. schools adopt open resources

The idea of a degree program without requiring any textbooks comes on the heels of Tidewater Community College, the first U.S. accredited institution of higher learning to offer a zero textbook degree.

In 2013, the community college in Virginia designed a curriculum using open resources that allowed students to skip nearly $3,700 in textbook costs and achieve a two-year degree in business administration, which they call the “Z-Degree,” according to its website.

In the pioneering year of the Z-Degree, the school reduced the cost for graduates by 20 to 30 percent and saw a significant increase in the percentage of students completing courses with a C or better, according to the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Daniel DeMarte, vice president for academic affairs at Tidewater Community College, said by the end of the spring 2017 semester, 10,221 students will have completed a Z course.

DeMarte also said the school is developing additional Z-Degree options for students in criminal justice, social sciences and general studies.

Other schools in the U.S. have followed suit, with over half of the states now using open resources in some form, according to a list by Creative Commons.