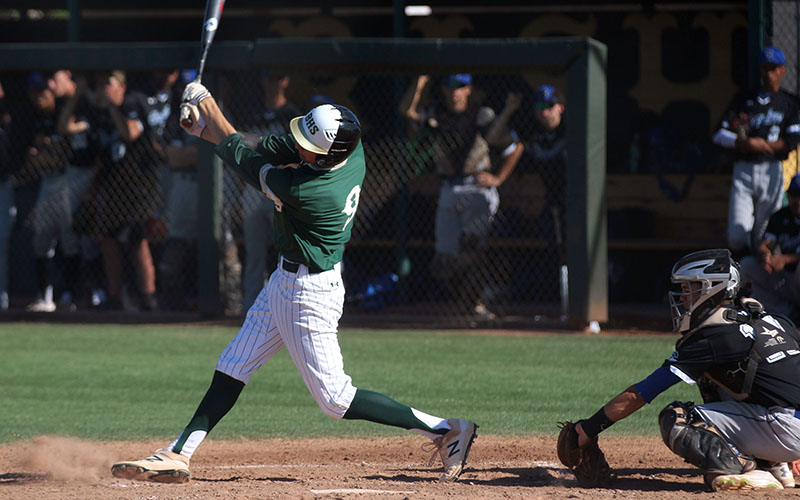

Basha infielder Gage Workman swings at a pitch in the first inning of a game against Chandler High. Coaches in high schools are now using analytics to spot trends and improve performance. (Photo by Tyler Drake/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX — Ask anyone involved in sports, and they will probably know that high school athletics often mirror concepts from professionals. This especially rings true with the increased use of major league-style analytics in high school baseball.

“We do a lot of advanced scouting,” said Basha baseball coach Jim Schilling. “As far as analytics go, studying numbers, if their numbers are on MaxPreps, we do analyze those.”

MaxPreps, an online high school sports statistical database, keeps track of a player’s most important statistics, like batting average, RBI and home runs, which coaches and college scouts can access. And with the increased attention to data and statistics, there are applications like GameChanger, which allow coaches to upload the data from each game in a matter of minutes.

However, an abundance of data can create headaches.

“Having the kids’ stats online can be a pain because if you screw something up, they are all over you,” Schilling said. “That can be a little challenging at times, plus more work. The easier side, it is nice to see what other teams have. A lot of teams put their stuff up there so it works out.”

Baseball wasn’t always so data driven, but since “Moneyball” concepts were brought to the game by Oakland Athletic’s manager Billy Beane in the early 2000s, the majors have changed forever.

MLB analytic revolution

Luis Gonzalez, an outfielder with the World Series champion 2001 Arizona Diamondbacks, was winding down his career when analytics began to take hold in the sports..

“Our generation was different. Now we see it because kids are more (technology driven) than ever,” said Gonzales at the Society of Baseball Research Analytics Conference in Phoenix. “A lot more thinking (goes) into the game, and statistically it has changed a little bit.

Basha pitcher Kyle Wullenweber throws a pitch in the first inning against Chandler at Basha High School in Chandler. (Photo by Tyler Drake/Cronkite News)

“I am getting to learn a different side of the game, and you never really thought about it because back then you just showed up and guys played the game hard,” Gonzalez said. “You take a guy out, drink a beer and then get ready for the next game.”

Randy Johnson, one of Gonzalez’s 2001 teammates, shared similar sentiments regarding the time when analytics really began to take off.

“We have come a long ways. Numbers were important back then, too, but numbers have grown so much,” said Johnson, a pitcher who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2015. “We have come so far in every sport, but especially baseball in analytics. That is so much more pertinent now to (the media), the players that play the game, the coaches, the scouts, all that. That wasn’t as much to us, or the generation before us.”

Jessica Mendoza, former outfielder for Team USA Softball and now an ESPN baseball analyst, has noticed a difference since she began covering baseball in 2014.

“The managers are the ones involved the most,” she said. “I feel like the players aren’t always the ones asking for the data. The managers bought into it a lot more . . . I see the growth in the managers more than anything.”

High school takeover

The growing interest in gathering and analyzing statistics used by professionals has begun to trickle down to collegiate, high school and youth levels.

While coaches use these tools for preparation and evaluation, players have taken notice of their own production, but not without consequences.

“The one thing we see now with a lot of young players … some guys just over-analyze,” said Gonzalez, whose son plays third base at Chaparral High School and committed to Texas Christian University. “They haven’t even got in the dugout yet and they’re beelining straight into the video room to watch that at bat. You’ve got to put that behind you.

“I think it’s one of those processes (where) you have got to slow guys down. It’s great for the coaches and everybody else, but the players still have to go out there and play the game,” Gonzalez said.

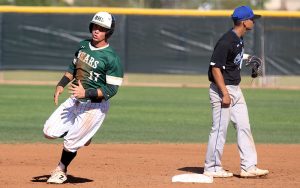

High school players such as Basha catcher Seth Beckstead, seen rounding second base during a game against Chandler High, are benefitting from the same use of analytics as professionals. (Photo by Tyler Drake/Cronkite News)

But coaches are aware of the problem.

“We try to not have them think about it; the batting average is evil in our eyes,” Schilling said. “We’re more into QAB’s (quality at-bats) and things like that. High school is a little bit different than college and the pros, for sure.”

However, a player’s analytics in high school can affect their future in the sport.

“There are scholarships on the line, those numbers matter. The higher their numbers can be, the more money they might get, it’s a new age as far as scholarships and things like that,” Schilling said.

Despite the benefits data provides to players and coaches, there are several hurdles coaches at lower levels of the game face that big league managers don’t.

For instance, in the major leagues, analytics used to identify trends for pitchers and hitters are available from a much larger sample because of the 162-game schedule. So data about where a pitcher releases a particular pitch, or the aggressiveness a batter demonstrates in a certain situation is likely to be more reliable than tendencies over a 30-game high school season.

In addition to shorter seasons, high school baseball rosters turn over every season.

“Some teams won’t have that many guys coming back. We do keep running charts on guys from year to year and that helps, especially when you have a player that’s been starting since he was a sophomore. But if you have a new kid out, like half our team (this year) is new, it’s hard for teams to really gauge,” said Schilling.

Ultimately, like any piece of data in sports, it all comes down to how it is used that makes it an effective tool.

“The numbers are important,” said Johnson. “But they are only important for Gonzalez and me and every other player if you can execute and apply those to how you can get a hit off the pitcher, or how they can apply to me getting a hitter out.”