Kelly Liebermann, engineer paramedic for the Phoenix Fire Department, says childhood drownings are the most emotionally taxing for firefighters in the Valley. (Photo by Becca Smouse/Cronkite News)

Jacob Hulett, 16, participates as a victim in a mock drowning demonstration by the Phoenix Fire Department on March 30 in Phoenix. (Photo by Becca Smouse/Cronkite News)

Becky Hulett, aquatics supervisor for City of Phoenix’s Parks and Recreation department, holds up a life jacket available for use at pools around the Valley. (Photo by Becca Smouse/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX — Firefighters have experienced it all. Blazing house fires. Fatal heart attacks. Toxic gas leaks. Crews are dispatched to a scene, follow the basic protocols and return home to the station for dinner, relatively unscathed.

But in Arizona, there’s one call that makes even the toughest first-responders anxious: Drowning involving a child.

“They are horrible,” said Kelly Liebermann, engineer paramedic for the Phoenix Fire Department. “Mom could be running out there with a purple baby in her arms, dangling, throwing it in your hands, like, ‘Do something.'”

For a landlocked state, life jackets and floaties would seem like unlikely sightings in Arizona’s deserts. But toddlers in the Grand Canyon state are far more likely to drown compared to rates of childhood drownings from around the nation — and authorities say they’re nearly all preventable.

-Kelly Liebermann talks about the emotional impact of being called to a child’s drowning.

The state’s constant warm climate keeps pools open year-round, the most common environment for drownings involving toddlers. Per capita, Arizona children aged 1 to 4 drown at a far higher rate than the national average.

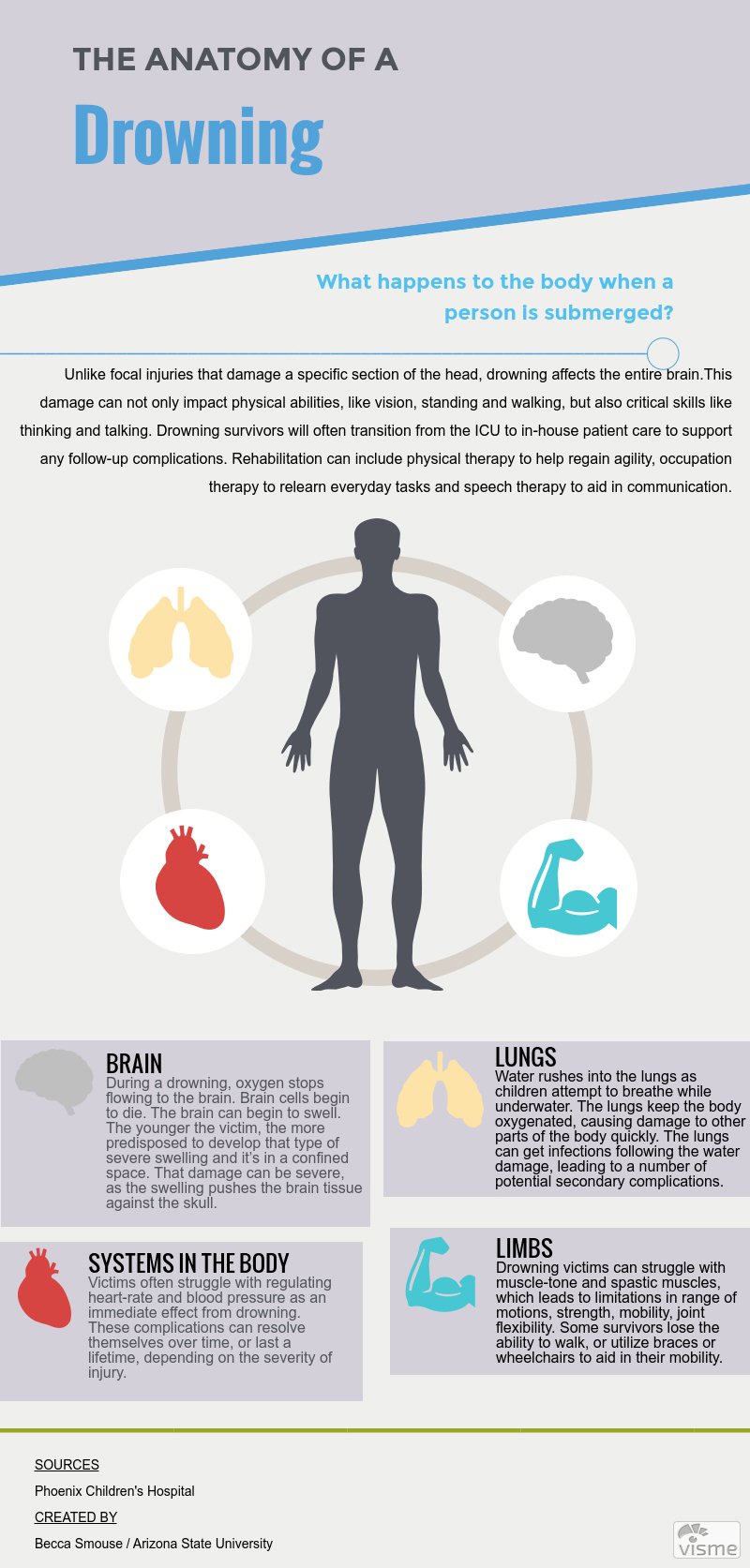

For those who survive, recovery could last a lifetime. Victims are subject to a range of complications including brain trauma, the inability to speak, walk or even feed themselves.

Taking steps to keep kids safe

1. Low-cost swimming lessons: The Phoenix Fire Department, the City of Phoenix Aquatics program, Salt River Project and the Arizona Diamondbacks partnered to offer low-cost swim lessons for children and adults. For lessons in your area, contact the Phoenix Fire Department.

2. Playing it safe: The Phoenix Children’s Hospital offers a free hands-on workshop for parents, teachers, babysitters and others on proper etiquette around water. Contact the hospital for information.

3. Financing fencing: The United Phoenix Fire Union Charities and SRP offer free pool fences for families in need. The Pool Fence Program has provided more than 800 fences across the Valley. Applicants must be homeowners with a child under age 6 at home, and meet income qualifications.

4. Life jackets in pools: City of Phoenix Aquatics offer free life jackets for public use at pools across the Valley. The jackets have been donated to the city to help keep kids safe around the water.

5. CPR Awareness: SRP offers free water-safety material, including a CPR video created by the Phoenix Fire Department with step-by-step instructions on giving CPR to adults, children and infants.

6. Boss of the pool: Phoenix Children’s Center for Family Health and Safety is encouraging parents to adopt the “Boss of the Pool” strategy, in which parents give constant supervision around water and set aside all distractions, including cell phones, while monitoring the pool. When multiple kids are involved, adults should switch supervision every 15 minutes with another sober, undistracted adult. Parents and families interested in more materials can contact Tiffaney Isaacson of the Phoenix Children’s Hospital directly.

Drowning rates in the state have flattened, tapering off after a steady decline that followed a push from fire departments and hospitals to educate families on water safety, as well as state ordinances to keep pools more secure.

But with drowning continuing to be a leading cause of death for toddlers, the state has more work to do.

Experts say drownings involving children follow a similar pattern.

An unattended child wanders off, falls into a pool. Submerged, he begins to panic and doesn’t think to hold his breath. His lungs begin to fill with water. Oxygen stops flowing to his brain. Brain cells begin to die. The brain swells against the skull. The child loses consciousness.

That was the story of 4-year-old Stryder Grub, who drowned in his backyard pool at 11 months old.

His dad found him unconscious. Panicked, he raced to a neighbor who began administering CPR until first responders arrived.

Stryder’s story: “It’s a miracle”

-Video by Becca Smouse

“When I got (to the hospital), there was a team working on him and he was breathing, but he was kind of unresponsive,” said Terri Grub, mother of the Phoenix toddler. “They let me crawl onto the gurney with him and hold him.”

Physical impact on the body

Phoenix Fire Department officials say they average about four minutes response time to a drowning call. Medical experts say even with that speed, damage is already done.

“By the time they get to us, they can already have some significant problems,” said Dr. Laura Wilner, who specializes in physical medicine and rehabilitation at Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Drowning victims fall into two categories: Fatal and non-fatal. Some children will succumb to their injuries shortly after being pulled from a pool or bath. Others begin to recover.

While in the intensive care unit, drowning victims can begin seeing the immediate effects on the body, struggling with regulating blood pressure or losing flexibility in their joints, becoming stiff.

Drowning in Arizona

Arizona regularly ranks in the top five states for drowning, according to Phoenix Children’s Hospital Water Safety Coordinator Tiffaney Isaacson. The state rate is more than twice the national average. Drowning is a particular problem for young children.

In 2016, there were 157 drowning-related incidents across Maricopa and Pinal counties, which account for roughly 60 percent of Arizona’s total population, according to Children’s Safety Zone. Of these incidents, 90 involved toddlers and infants. Sixteen died as an immediate result of injuries.

In the first three months of 2017, three children died from drowning, according to Phoenix Fire’s Liebermann.

“It’s an ongoing issue and battle,” he said. “We don’t have a large ocean next to us, yet we have one of the highest population drownings in the country, and why is because we have so many pools.”

While the fire department receives a wide variety of calls, responding to a drowning involving a child is the most emotionally taxing for the crew.

Fire departments administer mock drowning simulations to expose new crew members to the atmosphere, as well as inform the public of proper steps to take: Call 911 immediately and administer CPR.

Tension lingers in the air, even when the crew returns back to the station. Anger boils in the group, hitting home especially for those who have small children of their own, like Liebermann.

“You can’t justify a drowning,” he said.

Libermann started teaching his daughter how to swim at 6 months old. But, as PCH’s Isaacson said, nothing replaces adult supervision.

-Liebermann talks about the frenzied response to a drowning, and the fallout.

Drowning accounted for 4 percent of all child deaths in 2015, according to the Arizona Department of Health Service’s Annual Child Fatality Review, which represents childhood deaths across the entire state. Of the 30 deaths that year, 97 percent were deemed preventable by safety officials.

Isaacson said these rates have remained relative steady over the past several years. The state saw a sharp decline about two decades ago after ordinances were passed to regulate pool safety.

According to A.R.S. 36–1681, swimming pools and other contained bodies of water are required to be enclosed by at least a 5-foot wall, fence or other barrier. The gate must open outward from the pool, and must be self-closing and self-latching, with the latch located at least 54 inches above the ground or on the pool side of the gate.

Recovery: “It’s a process”

Between 5 and 20 percent of drowning survivors will likely suffer lifelong disabilities, according to research by Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Recovery can be unpredictable, Wilner said. Some may regain most, if not all, abilities they had prior to the drowning. Others may never get back what was lost.

The physical impact on toddlers and infants is hard to measure, as victims in this age group have yet to learn everyday skills. This makes rehabilitation more difficult for doctors like Wilner.

“The challenge is being able to predict where they are going to be in the future, because we can’t just rehab them back to what they were able to do, because there are so many things that have yet to do,” she said.

Younger victims are also more likely to suffer from major swelling of the brain, which can lead to a multitude of secondary complications. These deficits can cause infants and toddlers to rely more heavily on their families, Wilner said, making it challenging for them to grow independent of their injuries.

Older victims pose their own challenges, as they have loss to account for. Wilner said a drowning victim can lose learned skills immediately, and get pushed back in school because of his or her deficiencies.

Most survivors will need to create a new sense of normalcy, Isaacson said.

Miracles are possible. Children have walked away with little to no lingering complications.

Emily Eoff, a student at Midwestern University in Glendale, drowned at 22 months old in her grandmother’s backyard pool. Blue and not breathing, she was transferred by helicopter to a hospital nearby.

She walked away with no physical deficits.

Eoff: “I feel like … I need to give back”

-Video by Becca Smouse

“It’s hard when you have survived something that other people haven’t or that most people don’t,” Eoff said.

But every case it different.

“Everybody always wants that miracle, and that doesn’t always happen,” Wilner said.

The family dynamic

The unpredictability of recovery often puts strain on families, especially parents.

Depending on the severity of injuries, a child could spend weeks in the hospital recovering. Parents are forced to readjust their daily schedules. Other children in the family often feel stress, struggling to understand the situation fully.

Isaacson said many families fail to understand survivors of a drowning may suffer from complications that can shorten life dramatically.

Eoff’s family still feels the emotional impact of her drowning more than two decades later. Her sister can still visualize Eoff has a toddler, submerged at the bottom of the pool.

“I have happy memories from the whole situation because I’m fine, and they have all of the scary moments and the guilt,” she said. “It was 25 years ago … and my mom still won’t talk about it.”

While hospital staff hope every victim has a full recovery like Eoff’s, history has shown that many will walk away with lingering complications. Wilner said it can be difficult for families to come to terms with the possibility their child may never fully recover.

“It’s a challenge to walk that fine line between giving families hope, but at the same time being somewhat realistic,” Wilner said.

Wilner works directly with parents to teach appropriate support measures based on the severity of the injuries. She said she tries to help families look ahead and prepare for the child’s needs down the road, rather than get stuck on the immediate here and now.

Financial complications also arise. Families face battles with insurance and costs to cover hospital expenses. Some survivors could need equipment for long-term care, such as braces or wheelchairs.

PCH’s Isaacson, who works directly with families who have been impacted by drowning, said relationships within the family can dissipate without proper support, especially marriages and interactions with other children.

“The families tell me that it is more difficult to have a child who’s severely injured than it is to have a fatality,” Isaacson said. “Their child has changed forever.”

Phoenix’s Liebermann and his team experience this stress every time a drowning call comes through the station.

The call comes in, sounding a tone different from other calls for response. The atmosphere is tense, adrenaline is pumping through the firefighters.

Liebermann said crews rush to the scene, lights and sirens blaring. In a mad dash, they attempt to revive the child, calm the parents and rope in assistance from local police, all while internalizing their own emotions.

The response is difficult. But the survivor stories keep them grounded.

Stryder, now 4 years old, gets a visit from Phoenix fire officials every year on his birthday, acting as a reminder to the Grub family and the first responders that miracles do happen.

“It’s hard to explain the relationship and the bond…I don’t think it’s anything I could ever find words for,” Stryder’s mom, Terri, said. “(It’s) allowing them to celebrate his life and to give them an opportunity to get out of it what they need.”