PHOENIX — His name is not “John Elway’s son.” It’s “Jack Elway.”

Since the first grade, Jack Elway played football. He was surrounded by it his whole life. His father, John, is a Hall of Fame quarterback who won two Super Bowls. His grandfather, the late John Albert “Jack” Elway Sr., was an accomplished college football coach.

For a long time, he defined himself by his bloodlines.

“I will forever be John Elway’s son, obviously, because he is a legend,” Jack said. “By now I’m used to it. It doesn’t bother me at all.”

One reason is because the former Arizona State quarterback has forged his own path with a hat company called Mint Tradition. The high-end, customizable headwear is attracting attention after receiving the endorsement of several NFL athletes and being showcased at the 2016 ESPY Awards kickoff party.

“I want to take risks, make mistakes and put myself out there,” he said.

There’s a reason.

Elway spent much of his youth trying to please his dad and grandfather by playing football. His mom, Janet Elway, remembered the emotions Jack showed on their way to his games.

“There would be a lot of tears that he didn’t want anyone else to see just before the game,” she said. “He would sit in the car until his tears dried up, then bravely go out there and put on a brave face.”

In his last high school football game, with his dad as coach, he did not perform well. He threw several interceptions en route to a big loss. The other team’s fans started chanting, “Elway, Elway,” mocking his performance.

“That broke my heart for him, to see your son being mocked,” Janet said.

In 2009, Jack Elway entered his first season of football at Arizona State in an unhealthy mental place. He explained it as “imposter syndrome,” a phenomenon named by two U.S. psychologists that is described as an inability by high-achieving individuals to internalize accomplishments while living in fear of exposure as a fraud.

“I never really, truly believed that all of my success that I was doing in football was because of me,” Jack said. “I was always kind of brainwashed to think I was only doing well because I was John Elway’s son.”

He was surrounded by negative talk, consumed by self-doubt and believed he was spiraling out of control. He realized it would be best for his mental health if he stopped playing football.

“He never wanted to let his dad down,” Janet said. “All of a sudden I got a call, he said, ‘Mama, I can’t do it. I’m quitting football and don’t tell dad.'”

“I think it did as come more of a shock to my dad, because obviously Jack just really wanted to live out his dream and my dad’s dream, too,” Jack’s sister Jordan Asher said.

Playing in the shadow of a Hall of Famer was a difficult place to be.

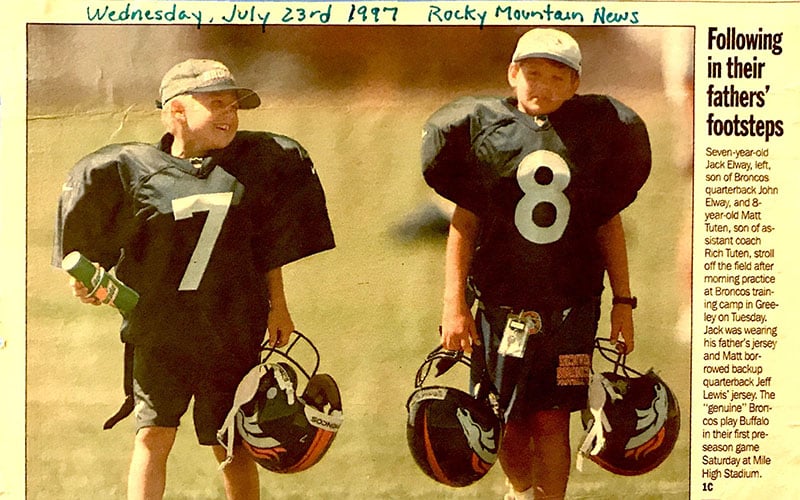

Jack Elway and Matt Tuten at youth football practice.(Photo courtesy of Jack Elway)

John Elway was unavailable for comment but told the Denver Post in 2009 that he supported his son’s choice to leave football.

“It’s like the world has been lifted off his shoulders,” he said. “So I’m happy for him.”

Jack Elway admits now “it’s hard for me to look back on. It was such a mental, tormenting place that I was in.”

A single moment didn’t prompt him to leave the sport, he said. The last name on his jersey brought more outsider and media scrutiny than most young players endure. Jack believes self-doubt was the leading factor in his decision to hang up his Elway jersey.

“You start doubting yourself, you start performing worse, you start spiraling down. Before I knew it, I was so lost,” he said. “It (football) was really my passion. Even today I dream about it all the time. It’s engrained into who I am.”

He spent the 2009 season at ASU as a redshirt. He was in a five-way battle for the starting quarterback position the next season but decided to quit.

He admits he never knew how to ask for help, from when when he played youth football to competing on ASU’s Frank Kush Field. The burden of working through self-imposed expectations and the ones set by family and onlookers was left up to him.

Football gave the young Elway a lot, he said, including discipline, friends and purpose in life.

Afterward, he realized how much it had become part of his identity.

He was lost.

The next four years were some of the hardest. He struggled with his identity.

He graduated from ASU early with a degree in economics and immediately went to California to work at his dad’s Toyota dealership in Manhattan Beach. He had three sisters who weren’t involved so he felt a need to learn that side of the family business. He took in all he could during the next four years, with the thought of running a car dealership in the future.

“It was hard to be OK with that,” he said. “It was something I wasn’t super passionate about. I didn’t love the business.”

He felt unfulfilled. He was drowning and unhappy. One day at the dealership, he decided to quit and return to Colorado. Things would only get worse.

In 2014, following an altercation with a girlfriend, he pleaded guilty to a charge of disturbing the peace and was sentenced to probation and domestic violence counseling.

“It was devastating for me,” Jack said. “Ever since I quit football, up until a few years ago it was like hell for me, honestly.”

His reputation took a hit.

“That was something I really prided myself on my whole life, was being a good person,” he said. “I took a ton of pride in my character and to have my character stripped away from me like that was really hard.”

After believing he hit rock bottom, an opportunity presented itself.

Growing up, Elway wasn’t spiritual, but in his dark time he turned to Buddhism and began meditating daily. It was one of the key components in his life that altered the way he thought and perceived the world, and it made him appreciate the little things more.

He wasn’t sure what to do. Opportunities arose, but he knew he wanted to have his own business and build something that came from his work.

One night in a club, Elway noticed the hat of a patron. He asked the man where he bought it. Geoff Muller said he made the hats in his basement and was going to school for fashion design. Muller became Elway’s mentor and showed him the possibilities in the industry. It was a different career path than the one he and his father knew.

“It’s a whole world he doesn’t understand,” Jack said. “It was hard for me to eventually make the leap and be like ‘OK, I’m going to go for this.'”

As a child, Elway was often drawing and exploring his creativity. To this day, he wishes he could return to college and take photography, illustration or art classes.

An idea came to him for a company: Mint Tradition.

“The whole idea is kind of creating new traditions,” Elway said. “Kind of breaking free from what you’re used to doing. Doing something different. Making your own tradition.”

Mint Tradition Broncos custom hat.(Photo courtesy of Jack Elway)

Elway’s vision was of high-quality hats made in the United States, using full-grain leather from the top 2 percent of hides in Europe. The tanning of the leather is mostly water-based material that limits the emissions of volatile organic compounds. The straps on the back are watch straps from a company in Florida. The hats, available for purchase at MintTradition.com., range from $210 to $410.

His whole family has supported the process.

“We are just so proud of him,” Asher said. “He has come a really long way. He is really driven. He is a really hard worker and that transferred over from football now to his fashion line.”

Jack has enjoyed finding what he believed he was meant to do.

“I wake up with a passion,” Jack said. “I wake up motivated because I’m excited for the day, not because I’m dreading the day.

“I’m so much happier than I was before.”