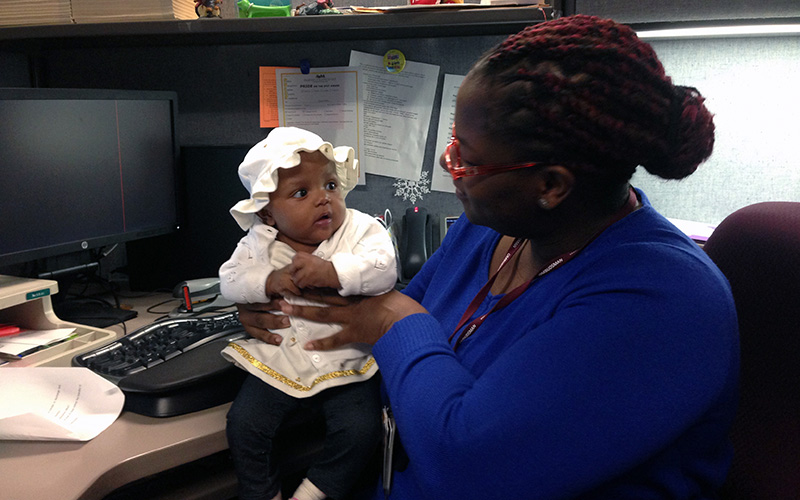

Christie Willis, 33, said bringing her four-month-old daughter SaNyah to her office at the Arizona Deparment of Economic Security hasn’t affected her productivity. (Photo by Saundra Wilson/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Babies cooing in strollers and on brightly colored play mats in their parents’ cubicles are commonplace at the Arizona Department of Health Services.

Co-workers gather during breaks, playing with one another’s infants.

Babies attend meetings and lie calmly (and other times not so calmly) as their parents go about their normal work routine.

Six-month-old Katelyn Watanabe lay on her mat, staring up at dangling plastic shapes hanging just out of her reach. Kevin Watanabe, her father, was in arms’ reach, sitting in his swivel chair, typing away on the gray desk in his cubicle.

“Knowing that she’s here with me I don’t have to worry about who she’s with,” said 32-year-old Kevin Watanabe, a nutrition consultant in the women, infant and children department and father to six-month-old Katelyn.

“Having the interaction with her, having that one-on-one time is beneficial to us,” he said.

Kevin Watanabe said he will miss playing with his daughter Katelyn at lunchtime after she ages out of the infants-at- work program at six months old. (Photo by Saundra Wilson/Cronkite News)

Babies up to six months old have been the norm at the health agency for more than 15 years.

Three more state agencies officially opened workplaces to employees’ infants in January: the Arizona Department of Economic Security, the Department of Water Resources and the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System.

Bringing babies to work has its benefits, including boosting employee morale, creating crucial bonding time for parents and reducing worries and costs of child care, advocates say, but it doesn’t work for every worker, infant or workplace.

How it works: baby retirement, breastfeeding and bright smiles

Parents have brought more than 200 babies to work with them at the health agency since 2001, when the infant-at-work program was established. The program, which allows infants up to six months old, began as a way to encourage mothers to breastfeed and gradually expanded to allow parents, grandparents and foster parents to bring infants to work.

About three to 15 babies among its 1,400 employees are at work at any given time, according to Dr. Cara Christ, agency director.

“You can see the office dynamics change,” Christ said. “People are happier and workplace morale increases with the baby around.”

Program requirements vary by agency and department, but generally parents bring their own supplies and must stay with their babies at all times.

Four-month old SaNyah joins her mother, Christie Willis, in her cubicle as a part of the new infant-at-work program at the Arizona Department of Economic Security. (Photo by Saundra Wilson/Cronkite News)

Gov. Doug Ducey supports the program.

“It’s a win-win-win – increased productivity, quality employees less likely to leave state service, and most important – happy babies,” Ducey said in his State of the State address.

Baby benefits: Why working parents bring baby to work

Christ said parents often come back to work sooner because of the program. Christ brought her baby to work and returned from maternity leave 5 ½ weeks after her daughter was born even though she had 12 weeks of paid leave.

When her daughter was “retired” from the program at six months, Christ said she and her colleagues were sad to see her go.

“It makes it more than work when you’ve got people that’ve held your baby and have comforted your baby and have watched them grow for six months, ” she said.

Watanabe, talking a few days before his daughter aged out of the program, shared Christ’s sentiment, saying his colleagues were quick to help him out with Katelyn.

Watanabe said Katelyn didn’t sleep much at the office because she enjoyed the interaction with his co-workers.

He said the father-daughter time was priceless.

“I came back a week after she was born just because I knew that I would have all of this time to be able to spend with her at work,” Watanabe said.

Baby brain: Connections to stimulate growing babies

Babies crave interaction during their first six months, according to Dr. John Pope, board president of the Arizona Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“There’s a lot of brain growth and development,” Pope said. “It’s one of the fastest times in their lives that it grows.”

For mothers, much of the initial bonding happens in the first six months and is connected to feeding, Pope said.

Fathers need bonding time too, Pope said.

State employee Kevin Watanabe has a stroller, car seat and playmat for his daughter Katelyn in his cubicle. (Photo by Saundra Wilson/Cronkite News)

“It’s really good for the dads to have time with the baby because we want the dads to be alright,” Pope said, adding that fathers can get more time with their child if they can bring them to work.

Pope said bringing babies to work also postpones the task of finding child care, a benefit 33-year-old Christie Willis appreciates.

Willis, who works for the state department of economic security, brings her four-month-old daughter SaNyah to work with her two to four times a week.

“It’s hard trying to find a childcare where you trust individuals because these are people that you don’t know,” Willis said.

Not so good news: When babies at work doesn’t work

The infant at work program comes with its challenges. Not all spaces are appropriate or safe for babies, and Christ says not all babies are ready for the working world.

Christ had two babies go through the program. One was the perfect candidate and stayed cool, calm and collected in the workplace. The other: not so much (she “retired” him early).

“A baby may get a little bit fussy in a meeting and moms and dads will step out and excuse themselves,” she said.

The program is limited to newborns and babies no older than six months because babies spend most of their time sleeping, Christ said.

“They’re not very active, they’re not mobile, they’re contained, they sleep, they eat,” Christ said. “At about six months is when they start to crawl and sit up and want to interact, and that’s when we’ve noticed it’s harder to continue to do the job with the baby at work.”

The program is open to employees who don’t work face to face with clients, but employees must gain permission from their immediate supervisor before the department’s assistant director signs off on it.

“There’s some areas where it’s not going to be appropriate to bring your baby to work,” Christ said, giving the example of someone working in a direct care position at a psychiatric office.

Christ says it’s important to make sure the environment is safe for a baby and that its presence won’t affect the employee’s productivity.

Libby Puccio Smith holds her daughter, Beckham, after she wakes up in her office at the Arizona Department of Health Services. (Photo by Saundra Wilson/Cronkite News)

“It’s not a one-size fits all policy,” she said. “Each employee should find out what works for them.”

Wanted: Work-life balance for struggling parents in America

About six in ten parents with infants or preschool-age children say that it’s hard to find affordable, high-quality childcare in their community, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center report.

Half of full-time working fathers reported having too little time to spend with their children, the report says.

For mothers, work arrangements are linked to how they feel about the amount of time they have to spend time with their children, according to the report. It found that almost 40 percent of full-time working moms wishing they could spend more time with their children.

Libby Puccio Smith, chief of workforce development at the health agency, is learning how to find that balance after returning to the office from maternity leave with 14-week-old daughter Beckham.

“This gives me the best of both worlds, that I didn’t have to give up my career and I’m still able to have that time,” she said.

Smith said she’s working to establish a new routine with Beckham accompanying her at the office.

And her work productivity? Smith says it’s increased.

“At home you can take time to be able to do things,” she said. “Now, in order to make sure that I’m getting things done, I have to be maximizing every minute that I have.”