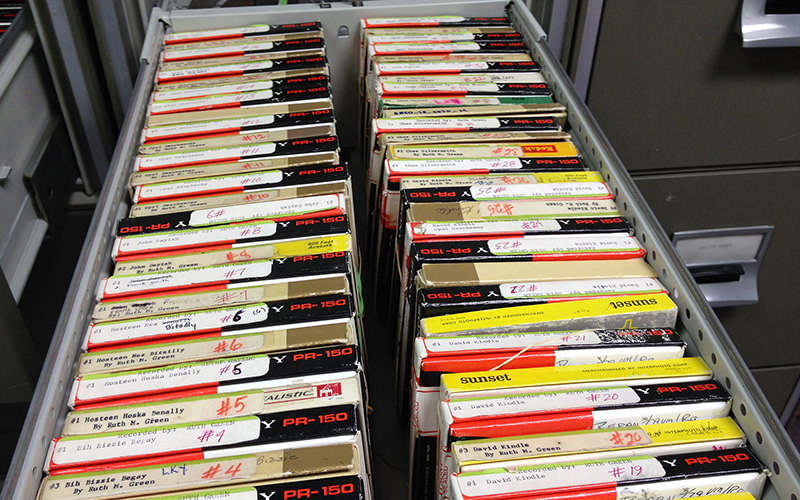

Some of the 300 reels of tape that were recorded decades ago, preserving thousands of hours of Navajo oral histories, songs and stories. (Photo by Irving Nelson/Navajo Nation Library)

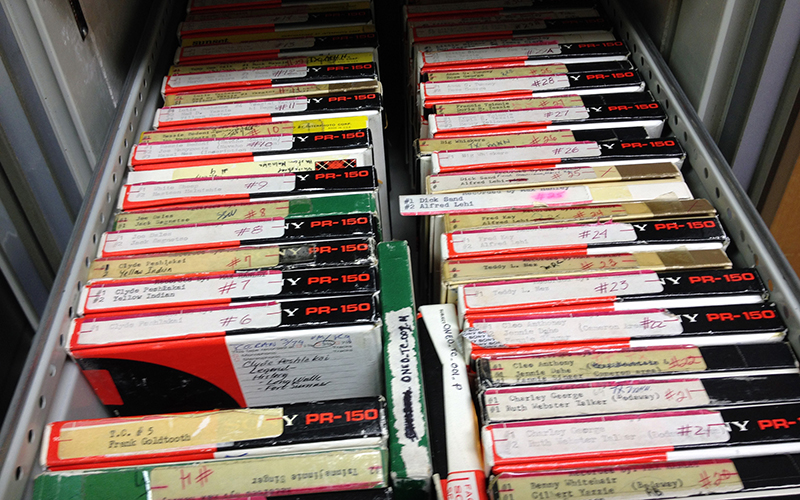

Navajo historians and librarians say no one has ever fully cataloged the tapes, but the parts they have listened to are a trove of tribal history and culture. (Photo by Irving Nelson/Navajo Nation Library)

The tribal history tapes have taken a circuitous path to the Navajo Nation Library, including being briefly unaccounted for only to be found in an empty jail cell. (Photo by Irving Nelson/Navajo Nation Library)

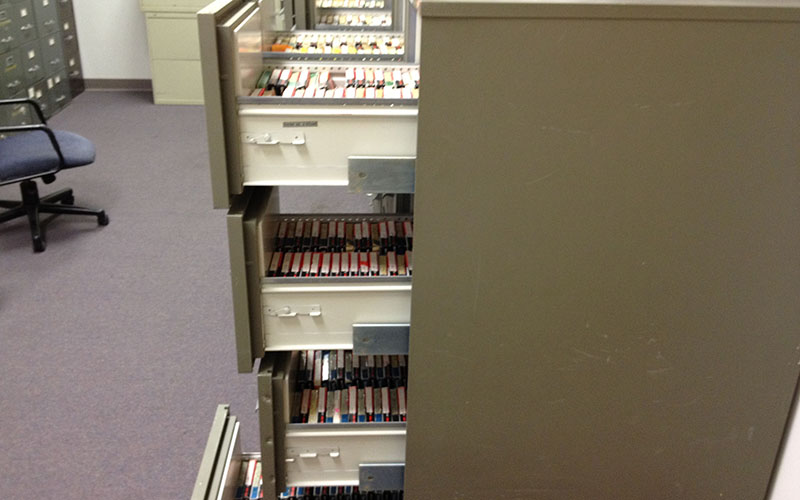

The Navajo Nation Library is seeking funds to digitize the five dusty filing cabinets of tapes so the collection can be protected and distributed to schools and others. (Photo by Irving Nelson/Navajo Nation Library)

WASHINGTON – Jolyana Begay-Kroupa still remembers waiting for the seasons to change when she was a child so she could hear the winter stories her Navajo grandparents would tell.

But Begay-Kroupa, now a professor of the Navajo language at Arizona State and Stanford universities, worries that “because my two boys grew up in the city … away from the Navajo elders they never got what I got … listening to grandma and grandpa tell certain stories in the winter.”

That’s why the preservation of 300 reels of tape, holding thousands of hours of Navajo oral history, is so important to people like Begay-Kroupa and Irving Nelson, program supervisor for the Navajo Nation Library and “one of the lucky ones” with access to the tapes.

“It was just an awesome experience to listen to a small, small portion of one tape,” said Nelson, an experience made even more powerful by the imperiled history of the tapes.

Misplaced for years, only to be discovered sitting in a jail cell, their backups destroyed in a fire, their entire contents never cataloged, the tapes must be preserved so that generations to come can hear the “knowledge, legends, stories, traditions stored on these tapes,” advocates say.

The library is asking the Navajo Nation Council for $230,520 to digitize the five dusty filing cabinets of tapes so the collection can be protected, distributed to schools and made available to others.

“We don’t even know everything that was recorded in the ’60s – there are thousands of hours and, as far as we know, everyone originally interviewed is now gone,” Nelson said.

“It’s incredibly exciting,” Nelson said. “I don’t … fully know where to start when explaining the journey, of this oral history.”

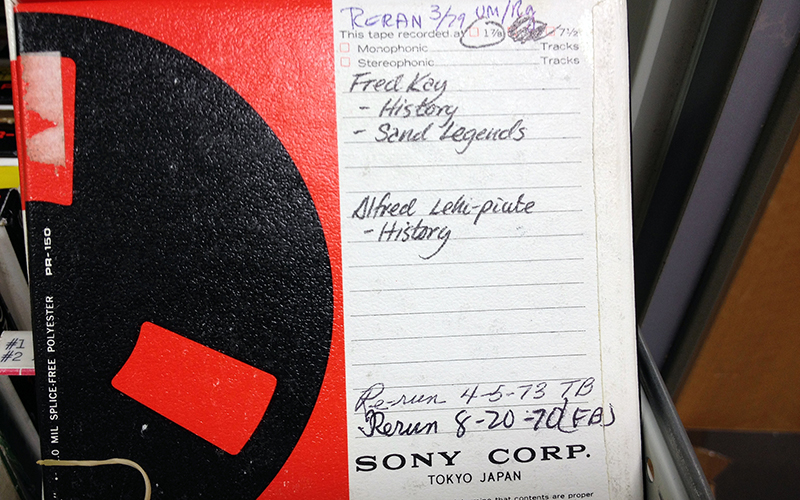

The journey began in 1968 when funding – Nelson believes it came from the federal Office of Economic Opportunity – was used by the Navajo Office of Economic Opportunity to begin recording oral histories.

“But we’re not fully sure what their plan for the tapes was, or even if many people knew they existed,” Nelson said.

The library acquired the collection in 1978 or 1979, Nelson said, after “they had just been found in an old jail cell at Fort Defiance.” Worried about the quality of the tapes after years of potential damage, the library secured federal funding in the late ’80s for the first preservation attempt – transferring the reels to cassette tapes.

“However the funding ran out before that long process was complete, so they didn’t get to all of them,” he said.

The cassettes they did get to were stored at the Dine College in Shiprock, New Mexico, but lost in a 1998 fire that also destroyed books, science equipment and a number of “priceless” Navajo collections.

Since then, the original reels have been stored in fireproof safes where they are protected from direct sunlight, extreme temperatures and any dust.

“The recordings are too precious to lose,” Nelson said.

They include thousands of hours of Navajo describing their daily lives and social life in their rural towns, as well as personal accounts passed down through generations, “personal histories … preserved from hundreds of years ago,” Nelson said.

Also on the tapes are dozens of songs, legends, stories, fables and a recording of the most sacred of all Navajo ceremonies, the nine-night ceremony, which involves hundreds of songs, dozens of prayers and complicated sand paintings.

“The content of these recordings are very culturally sensitive,” Nelson said. “There are some legends we only tell at certain times of the year and the nine-night ceremony is very sacred, very private.”

Which is why Begay-Kroupa is “so glad these tapes are in the care of the library.”

“Recordings of the nine-day chant were probably made because an elder was fearful the practice would be lost,” she said.

The library plans on coordinating with Navajo religious authorities to determine what recordings can be played when, as well as collaborating with educators to develop curricula on Navajo history, culture and language.

“Which will be the biggest legacy of these tapes I think,” Begay-Kroupa said. “That students and Navajo young people will be able to experience these ceremonies, teachings, our stories how they’re meant to be heard.”

She’s excited for her students to have access to these tapes as they embark on the “challenging but rewarding” journey of learning the Navajo language.

“Sometimes there’s a story we’re reading as a class and I can tell it’s an elder speaking based off how the person worded a phrase,” she said. “But it’s complicated to pick that up … it can be very subtle … so being able to hear the difference will be nothing but positive.”

According to Nelson, some of the ceremonies are recorded in “the old language” – a dialect that is no longer commonly used, which holds particular interest for researchers.

“It will be very useful for linguists to work with and study and document this dialect and how language is being used,” said Gwyneira Isaac, director of the Recovering Voices program at the Smithsonian Institution.

“Scholars will also get an opportunity to study history from a Navajo perspective,” Isaac said. “It’s unusual, you don’t always have this rich record … it’s very important for this to be part of a healing process if parts of their history have been hidden or lost.”

The journey of the tapes added a chapter this summer when Nelson was contacted by the daughter of Carl Gorman, famous Navajo artist and decorated code talker in World War II. Gorman was one of the people who traveled to all corners of Navajo lands in Arizona, Utah and New Mexico in the 1960s to capture the oral histories with the bulky recording equipment of the time.

“Her late father has conducted some additional interviews and she’s donating those tapes to the library so our collection can be complete,” Nelson said.

He said the benefit of restoring these tapes extends beyond the reservation, since the tapes “share a lot of the local history that’s of significance to the area.” The state histories of Utah, New Mexico and Arizona will all become richer when these personal histories are known, he said.

“The more people who know these environmental and cultural wisdoms the better, it speaks of a diversity of knowledges,” Isaac said. “This diversity encourages human diversity and makes us a more adaptable culture overall.”