QUEEN CREEK – When she was 5, Berenice Zendejas scribbled down the answer to her kindergarten teacher’s question.

“What what do you want to be when you are older?” the teacher asked.

Other students answered with starry-eyed dreams of one day becoming a ballerina or a princess, a scientist or a superhero. But for Zendejas, the child of Mexican immigrants, the answer was simple: she wanted to be a doctor.

Now 18, Zendejas is a soft-spoken young woman who likes to wear jeans, t-shirts and Converse high-tops. Her glasses frame thoughtful and determined brown eyes.

During a recent interview, she sat on a southwestern-styled couch in the living room of the Queen Creek home she shares with her family. The small wooden desk and black swivel chair where she studies late at night and early in the morning stood just a few feet away.

“I just always wanted to help people and make the world a better place,” she said.

But the road to success has been pitted with obstacles that children of immigrants and first-generation college students sometimes face.

For Zendejas, language barriers, cultural adjustments, family commitments and financial struggles were her greatest challenges.

A positive trend

Berenice Zendejas had always imagined graduating from high school and then entering a university just like the rest of her classmates.

But she spends much of her time caring for her younger siblings and nephew Ezra. Instead of immediately attending a university, Zendejas is a part-time student at Chandler-Gilbert Community College.

In September, she received a scholarship from the Arizona Interagency of Farmworkers Coalition. The scholarship paid for her tuition and books for her first year at community college, the first step in her long journey toward becoming a doctor.

Zendejas was one of several students who received the scholarship designed to ease the financial burden of higher education. Fernando Quiroz, the Arizona Interagency Farmworkers Coalition president, said he “hopes scholarship recipients will either become community leaders or pursue careers that provide services to the migrant community.”

When she graduated from high school and enrolled in college, Zendejas reinforced two positive trends in Hispanic education reported by the Pew Research Center.

The center reports an uptick in high school graduation and college enrollment rates among Hispanics in the United States.

Since the 1990s, the percentage of the Hispanics ages 18 to 24 pursuing a college degree has continued to increase, according to the Pew Research Center.

In 1995, 22 percent of Hispanics ages 18 to 24 enrolled in college. In 2014, Hispanic college enrollment shot up to 35 percent.

As a comparison, whites in the same age group during the same time period who were enrolled in college increased by 4 percentage points, from 38 percent to 42 percent.

The Pew researchers also found that during the same time period the high school dropout rate for Hispanics aged 18 to 24 decreased from 34 percent in 1995 to 12 percent in 2014.

In Arizona, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, Latinos make up about 30 percent of the state population.

“What’s unusual is that here in Arizona we are experiencing changing demographics at an accelerated rate,” said Joseph Garcia, the director of the Latino Public Policy Center for the Morrison Institute for Public Policy.

Arizona schools have seen an increase in enrollment of Latino students, he said, and must provide proper educational opportunities for the growing Latino population. The inherent problem, he said, is that many schools with high Latino enrollment are not adequately funded.

While the nation’s educational progress for Latino students has improved, Arizona has lagged, Garcia said.

In Arizona, the Latino graduation rate has been almost flat from 2011 to 2015. It moved up from 72.2 percent to 72.3 percent.

“The idea of college is not in their [Latinos] environment or in their neighborhoods – it’s not in their plan,” Garcia said. “There are a lot of obstacles that are built into that first generation of Latinos who are seeking college that they have to overcome.”

Berenice Zendejas knows this firsthand.

Cheering for Berenice

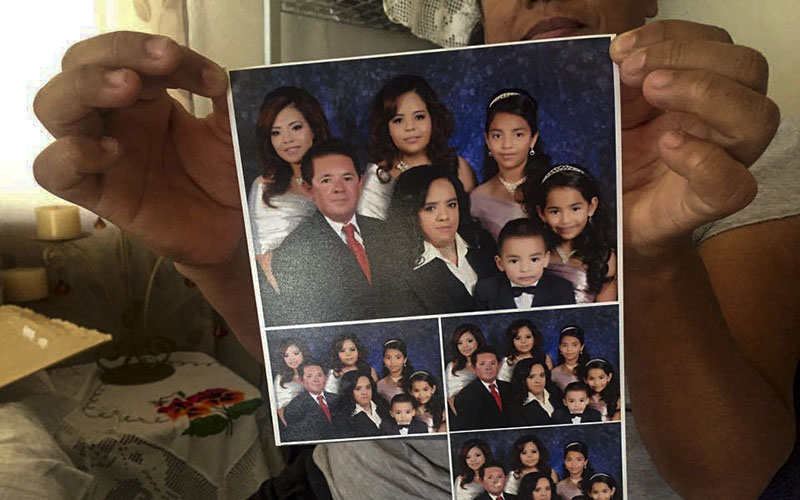

Zendejas’ parents, Berta and Francisco, grew up in the Mexican state of Michoacan.

Francisco, a former farmworker, obtained a green card in 1986 through the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. Berta and Francisco married in Mexico in 1994. She was 22 when she crossed the border to join her husband that same year.

She came from a large family — 10 siblings raised by a busy stay-at-home mother and a hardworking father in Mexico.

When she first came to the United States, it was hard to adjust because she missed her home: the traditional food, her family, her friends.

But Berta, 44, now considers Arizona her home. Her husband is an American citizen. The couple now has five children. When the family visits Michoacan, she misses the familiarity of her Queen Creek home.

For about 18 years, Berta has worked as a custodian at Queen Creek High School. Francisco, she said, has worked full-time at a lumber company for more than 15 years.

“Between me and my husband, we have enough to feed the family, to keep a roof over our heads and enough for the bills,” Berta said.

Berta added that life in the United States has provided educational opportunities for her children that would have been improbable if they had been raised in Mexico. Her family members in Mexico say there is little government funding for schools there, which causes financial hardships for parents seeking to send their children to post-primary schools.

Still, Berta said, it’s difficult to fund higher education in the United States. She and Francisco can’t provide the necessary funds for their daughter’s college dreams.

Yet Berenice is the only woman out of her 29 cousins to pursue higher education, according to Berta.

“My husband and I are very proud that Berenice is pursuing a college education and that is the main reason why my husband and I are doing everything we can to support her and provide for her as long as she is doing her part academically,” Berta said.

Berta said she and Francisco “felt very happy and very excited” when Zendejas got the AIFC scholarship because their daughter’s financial burden would be lightened.

They’re cheering for Berenice, she said. And they’re even prouder that she has expressed gratitude and appreciation for all that her parents have done to help her on her academic journey.

‘Don’t let anyone stop you.’

Zendejas was motivated by her parents’ work ethic to pursue a college degree.

“They are hard workers, I never see them take a day off,” Zendejas said. “I see their dedication and willingness to provide for us and just make our lives a little bit easier.”

“They just always taught us to do everything we can, they set up my example, and I want to be like them,” she said.

But Zendejas said her parents didn’t know a lick of English and had a hard time understanding their school assignments.

Zendejas and her siblings grew up relying on each other for academic support while their parents worked.

Outside of the home, Zendejas was sometimes discouraged by peers. They would note that medical school is hard to get into and that the field is dominated by men. At first it made her question her goals, but ultimately, she said, it made her “push a bit harder and try harder.”

Since she was 8, Zendejas and her older sister helped raise her two younger sisters and brother.

But since her older sister moved out recently to start her own family, Zendejas now cares for her three younger siblings who are still in primary school, as well as Ezra.

“By me pursuing college, I am definitely setting an example for them,” she said. “I am doing it for myself, but also for my family because I know they look up to me.”

As she spoke, her 9-month-old nephew Ezra bounced in his baby carrier and yelped for attention.

Her days consist of caring for her siblings and Ezra with a few hours of dedicated studying sprinkled in between.

“Not everything goes as planned and I am still pretty happy to be going to community college and to still be doing what I want, but I am still facing some obstacles,” she said.

Zendejas plans to apply for more scholarships to fund her planned educational path from community college to a major university.

One of the scholarships she is looking into would fund tuition and housing for one year at Arizona State University.

“I want to continue my education at a community college, transfer to a university and just get good grades,” Zendejas said. “That’s really important. And then hopefully go to medical school.”

It hasn’t been an easy road, but the hardships have strengthened her determination to live her dream.

“Don’t let anyone stop you from doing your dreams,” she said. “I’ve had moments where … I doubt myself but, in the end, I know I am making the right decision and I am happy for that.”