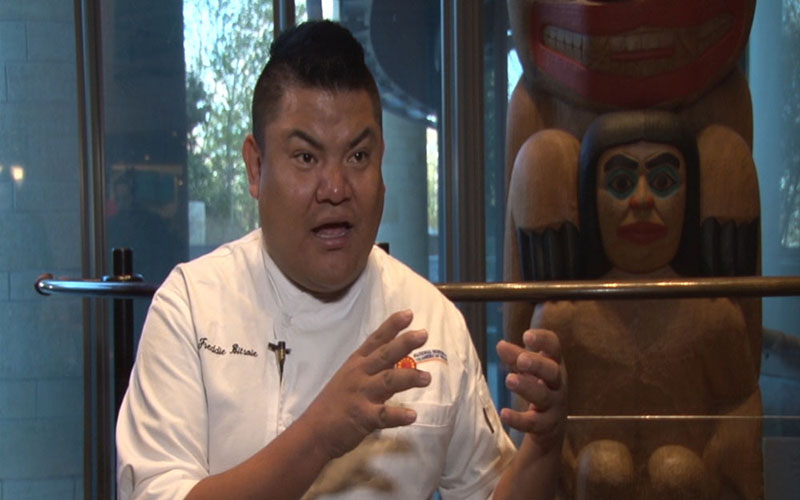

Freddie Bitsoie, a Navajo who is a clasically trained chef, said he sees part of his job at the National Museum of the American Indian as being a “curator” for the food histories of Native Americans. (Photo by Claire Caulfield/Cronkite News)

The foods that Navajo chef Freddie Bitsoie prepares at Mitsitam Cafe may not be familiar to an elder, but are all based on native foods and recipes that have been allowed to evolve. (Photo by Claire Caulfield/Cronkite News)

Freddie Bitsoie, who started to learn to cook by watching cooking shows as a child, said his college majors – anthropology and art history -combined to help lead him to his current “dream job.” (Photo by Claire Caulfield/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – Classic French, Italian and Japanese food are all highly regarded in the culinary community, but traditional Native American dishes?

“Where are the classic dishes that Native people have been making?” asks chef Freddie Bitsoie, executive chef at Mitsitam Cafe in the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. “I want to tell a story with my dishes … and have these dishes be respected.”

That’s especially true this Thanksgiving, as the Navajo chef prepares for his first big event as head of the museum kitchen.

Clam soup recipe

Freddie Bitsoie’s “signature” recipe is a modernized version of the clam dish that New England tribes may have prepared. (Serves 4-6)

INGREDIENTS:

PREPARATION:

Place the leeks, onions, garlic, bay leaves, thyme and a tablespoon of olive oil in a pot. Cook until translucent. (Do not brown, add water if caramelization occurs).

Add the diced potatoes and sunchokes, then add enough chicken stock to cover everything in the pot. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat to a simmer and cook until the potatoes and sunchokes are tender. (The sunchokes will foam as they cook, like beans.)

Add the clams with juice, simmer for another minute, then serve.

His Thanksgiving Day menu at the museum will be a combination “what you’d think of as traditional American Thanksgiving dishes, but with a twist” and those that tell stories, like how tribal traditions in Nova Scotia became New England clam chowder.

“When people come here my job is to give that representation for every tribe out there, and that’s kind of a heavy thing,” Bitsoie said. “It kind of unofficially makes me a food curator for a Native American food exhibition.”

It’s been a long journey from the Navajo Nation, where Bitsoie was born and taught himself to cook at a young age by watching cooking shows on PBS, to the “absolute dream job” that brought him to D.C. just three months ago.

“Living on the reservation we only had access to five television stations,” Bitsoie said. “I had no inkling of being a chef … but I would watch the cooking shows all day.”

Bitsoie and his family moved around throughout his childhood, living in Utah, New Mexico and Arizona before settling in New Mexico. He attended the Gallup branch of the University of New Mexico so he could be close to his family.

He said he “had no idea what I wanted to major in at first,” but something clicked in his first anthropology class. Bitsoie majored in anthropology and minored in art history, “and little did I know that those two disciplines would guide me toward food.”

When a professor pulled him aside to point out all his essays had a connection to food preparation, preservation or cultivation, Bitsoie “kind of blew it off.”

“But when I went home, I turned on my kitchen light and there were my pots hanging from the ceiling, my KitchenAid mixer was on the counter and I thought: Are there any other college kids who have a kitchen like this?” he said.

He soon “took the plunge” and enrolled in the Scottsdale Culinary Institute. He appreciates the technical skills he learned, but wanted to “enrich my understanding about food history from an academic perspective.” So Bitsoie went back to his anthropology roots and began researching Native food preparation techniques.

What he found was a lot of classic French or American dishes, just prepared with native ingredients. So he turned his “Native American cuisine journey” into a more academic look at the ingredients.

“And this is really where my art history came into play … because food history isn’t like history in a history book and neither is art history,” he said. “It evolves.”

“I was looking at prickly pear, looking at salmon, looking at amaranth, looking at quinoa, at its particular journey. If these plants and animals started telling their journey about how they started to be consumed over thousands of years, that was the story I wanted to tell,” he said.

Bitsoie spent years studying native ingredients, learning from tribes around North America and speaking about the reputation of Native American cuisine. He was noticed by the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian and received a phone call out of the blue. He said he would have been happy to be

“the dishwasher or the prep cook … as long as I was working here.”

Instead he was offered the executive chef position.

-Cronkite News video by Claire Caulfield

Bitsoie brought his academic background to the menu and hopes visitors not only find the meal delicious, but that they also learn about their country. He points to the story of “one of my signature dishes … a clam soup with leek.”

“Tribes in Nova Scotia and Massachusetts had access to really good clams so what they would do is get the sunchokes and clams and add it and cook it with seawater,” but he knew that would not fly with modern diners, so he updated it.

“People say things like, ‘How can that be Native American if you’re adding leeks, thyme, bay leaf and chicken stock?'” he said.

“My job as a chef is to tell you there was an original dish hundreds of years ago and because people were making that particular dish, it got carried on. So when the British came … that’s when they added their cream and their butter and that’s how we get a modern day New England clam chowder.”

Although guests may be experiencing ingredients like sunchokes, hominy or bison for the first time, Bitsoie does not want to create “weird” dishes that might be featured on “these TV shows where people look at different culture’s food as a dare.”

“I think that’s so disrespectful to look at people’s food as a dare instead of something that allowed them to be sustained for hundreds of thousands of years,” he said. “Snails are … disgusting. But they’re French and that’s seen as higher on the food hierarchy than something like … hominy that’s delicious and high in protein and low in sugar.”

Despite Bitsoie’s training as a classical chef, and the many culinary awards that he and Mitsitam have won, diners here are still museum visitors, still tourists making their way through a cafeteria line with a tray. There are no waiters and no white linen tablecloths. But that can make their reactions all the more satisfying.

“I watch people grab their food and sit down and I’ll watch in disbelief like, ‘Wow, that’s my recipes, that’s my food,'” he said. “Those are stories that they’re eating.”