Viri Hernandez in her kitchen, a staging area for volunteers who revisit eligible voters in heavily Latino neighborhoods, on Oct. 29, 2016. (Photo by Andres Guerra Luz/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – On a recent Saturday morning, Viri Hernandez’s kitchen buzzed with urgent energy.

There were bagels on the counter, packages of water bottles on the floor, and a Spanish-language countdown that indicated there were 10 days left before the election.

Canvassing volunteers grabbed flyers, picked up water bottles and tallied the number of houses they were to visit that day.

Then Hernandez and the volunteers rushed out with clipboards in their hands and a goal: knock on 50 doors before noon to check on the status of eligible voters and their mail-in ballots.

“Their vote is critical,” Hernandez, 25, said of Latino voters, adding that elections are sometimes decided, by “a few hundred votes.”

Hernandez and other volunteers would speak with residents, encourage them to vote, help them mail in ballots. They would knock on doors every day until the Nov. 8. election.

“That’s the type of investment and time that is needed to change the culture of voting,” Hernandez said.

A strategy to engage Latino voters

Hernandez’s home in a predominantly Latino neighborhood was a staging area for volunteers for Bazta Arpaio, a Latino-led campaign to mobilize Maricopa County’s eligible voters to vote out Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio and not elect Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump.

The campaign is part of a larger strategy to use immigration hardliners like Arpaio, who conducted famous raids in heavily Latino areas in Maricopa County to round up undocumented immigrants, and Trump, who promises to build a wall on the nation’s southern border and deport all the nation’s 11 million undocumented immigrants, as triggers to create a culture of voting among Latinos in Arizona.

It’s a strategy that began in the mid 2000s with Arpaio’s immigration raids and the passage of harsh state immigration laws that culminated in 2010 with the enactment of SB 1070, the famous “Papers Please” law that was largely tamed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Latino voters could be a powerful Arizona voting bloc. The Pew Research Center reports 30.5 percent of Arizona’s population and 21.5 percent of Arizona’s eligible voters are Latino.

Nationally, the Latino electorate will turn out in historic numbers and will favor Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, according to pollsters and political scientists at Latino Decisions.

But reversing a course of voter disengagement in Arizona that has been years in the making is no easy task.

Now, there’s a concerted effort among Latinos in Maricopa County that melds the wisdom of older activists and the energy of younger, more galvanized Latino voters.

They hope to change the momentum this election season, to awaken the Latino electorate that is slowly shaking off their moniker as the “sleeping giant.”

The strategy, which includes relentless canvassing and family-based civic engagement, is working, advocates say.

One Arizona, a Phoenix-based non-profit that heads outreach campaigns to register Latino voters, consists of 14 organizations that collectively have registered 150,000 new Latino voters this year, the umbrella organization states on its Facebook page.

The non-profit was formed in 2010, after the passage of SB 1070, and its members create a “broad tapestry” focused on “voter registration, voter engagement, voter mobilization, election protection and issue advocacy,” the One Arizona website says.

The Arizona Secretary of State’s Office reports voter registration increases ranging from 8,642 to 13,293 voters in legislative districts that the Arizona Community Survey tags as more than 50 percent Latino.

Petra Falcon, the executive director of the civic engagement and immigrant rights group Promise Arizona, noted that many younger Latinos are now reaching voting age. As children, they feared their immigrant parents would be deported or jailed.

Rocio Iniguez, 27, is one such voter.

She was an undocumented immigrant who came to the United States from Mexico when she was 4 years old.

Her father began the application process for her and her mother to become legal residents. They waited in line 10 years. Once they were approved, they waited another five years before qualifying for citizenship, she said.

In total, Iniguez said it took 15 years for her to become a citizen.

She immediately registered to vote, and has already voted.

Iniguez believes more Latinos will vote this year because they are tired of the way they are portrayed in the public eye, especially during this election by immigration hardliner Trump, who denigrated Mexican immigrants when he announced his presidential bid.

That negative image of Latinos, Iniguez said, “gained more momentum with this election. And that’s something we want to stop.”

“I think it will be a good outcome this year,” she said.

The increase in Latino voter registration in Arizona is thought to benefit Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, who is more popular with Latino voters than Trump.

In a last push to woo Arizona’s Latino voters, Tim Kaine, the democratic nominee for vice president, gave a speech completely in Spanish to a mostly Latino crowd in west Phoenix on Thursday.

The activist

Viri Hernandez said she arrived in the United States when she was a year old. Her Mexican mother carried her through the Arizona desert, fleeing from poverty, from being afraid it would rain and the dirt floor would become mud, from worrying about her infant daughter getting sick and not having the money to get her medical attention.

One daughter had already died, she didn’t want Viri to die, too.

Hernandez was an undocumented immigrant for 23 years. She became a legal permanent resident last year through marriage.

She feels disconnected from Mexico, but in the United States, especially in Arizona, Hernandez said there’s “a very clear rejection of me, of people like me.”

“I identify with the idea of what America should be, but not of what America is,” she said.

Viri Hernandez revisits heavily Latino neighborhoods in western Maricopa County on Oct. 29, 2016 to ensure voters have mailed in their ballots. (Photo by Andres Guerra Luz/Cronkite News)

Hernandez said when her mother arrived in the United States, she came with the “illusion” that they would have equal opportunities to succeed. Instead, they faced discrimination and increasingly restrictive immigration laws, including SB 1070. That law turned Hernandez into an activist.

In June, Hernandez was arrested during a civil disobedience for blocking Central Avenue while protesting the U.S. Supreme Court’s tied vote on an Obama administration executive order. The order would have granted work permissions and temporary relief from deportation to law-abiding undocumented parents of American citizens and permanent legal residents. The tied vote meant that the executive action battle was remanded back to the lower courts, and no relief from deportation would come to the 4 million undocumented immigrants who might have applied for the program.

Hernandez said every time she organizes political events, she “is fighting for that America that my mom was willing to risk her life to find.”

And that’s why she is so involved in voter engagement.

Will the sleeping giant awaken?

Latinos, who make up almost a third of Arizona’s population, could be the deciding factor in who wins Arizona, said Mi Familia Vota National Field Director Francisco Heredia.

They could sway Arizona one way or the other if they turn out to vote this year and support the same candidate, said Richard Herrera who is an associate professor at the ASU School of Politics and Global Studies.

But engaging Latino voters has been a long, slow process.

In 2012, non-profits were two years into their energetic canvassing and engagement efforts to recruit Latino voters. Democrats ran Latino Richard Carmona, a decorated war veteran and former U.S. Surgeon General, for the U.S. Senate.

Carmona lost to Jeff Flake. Only 18 percent of Arizona’s electorate that year was Latino, according to Pew Center data.

Despite its significant presence in Arizona and the passage in the last decade of state immigration laws that many Latinos view as racist, the Latino vote reached a historic low in the 2014 midterm elections.

U.S. Census data showed only 23.1 percent of the Arizona Latino population voted in 2014. A slightly higher number, 27 percent, of eligible Latino voters cast ballots across the United States.

Herrera attributes the historic low Latino voter turnout rate to a lack of voting culture in Latino communities.

“Many of the same practices that were designed to prevent African Americans from voting were also in place to prevent Latinos from voting,” Herrera said.

“When people are discouraged from voting, then it can take generations for a habit of voting to take hold,” he said.

Jose Lopez, 23, has lived in Guadalupe, a Phoenix suburb with a 62.2 percent Latino population, most of his life. He said during a recent interview that he has never voted before. He says many eligible voters in his town are disaffected.

No matter who is in office, the town remains unchanged, he said, and the community has longstanding problems with drugs and gangs.

“Voting to people here is just another check mark on a paper or a computer,” he said. “We don’t see no outcome from it.”

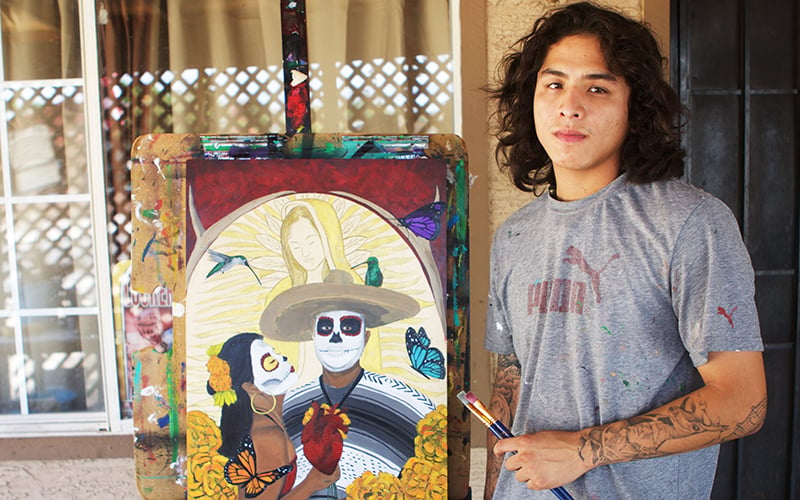

Guadalupe resident and artist Jose Lopez, 23, hasn’t voted in previous elections. He says many of his fellow residents see no point to voting because nothing changes in his town. (Photo by Andres Guerra Luz/Cronkite News)

When Guadalupe residents vote and don’t see change, it reinforces their hesitancy to vote, he said.

Phoenix resident and Bethany Bible Church Pastor Ricardo Félix, 45, said members of the Hispanic community haven’t traditionally voted because they either lack sufficient information about the election process, lack education or hope to eventually return to their own countries so they don’t really pay attention to what is going on in the United States.

“When they have been encouraged and received the information they need, I see them lean more towards voting,” Félix said.

Changing the energy of the electorate.

Falcon, a longtime civic engagement activist, works out of an office across a courtyard from a church sanctuary, a quiet place with pews, flowers, an altar, a cross and a stained glass window filtering light through vibrant reds, yellows and blues.

Pictures of doves decorate Falcon’s office. The dove is the symbol for Promise Arizona, the non-profit immigrant rights and civic engagement group she directs. It’s often called “PAZ,” the word for “peace” in Spanish.

Promise Arizona was created in 2010 to respond to the “anti-immigrant sentiment” in Arizona created in part by SB 1070, Falcon said. The law “really got people off of their couches,” she said. Immigrant parents became more politically engaged, and their American citizen children, who feared their parents would be deported under the harsh new law, vowed to vote when they were old enough.

Children marched with their undocumented immigrant parents at rallies.

Now that those children are old enough to vote, Falcon said, they are “changing the electorate and the energy of the Latino community.”

Promise began with a vigil to protest SB1070 at the Arizona statehouse. Falcon organized it. People who had never visited the state capitol sat under a tree praying that SB 1070 wouldn’t be signed.

After former governor Jan Brewer signed the bill, Falcon said vigil participants remained on the state capitol lawn for 103 days. Falcon and some participants of the vigil began building the infrastructure of Promise Arizona, which focuses on voter education and keeping in contact with voters even after the election is over.

It’s important to reinforce the idea the Latino vote “matters all the time” to change the culture of voting, she said.

Latino voters want to select their own candidates, the group educates voters on how to get informed about candidates and how to properly fill out ballots.

Not advocating for candidates allows the Latino community to “own their own voice,” she said, and vote based on what they value.

Falcon, now 62, was a young ASU student in the 1970s, during a time of widespread political change in Latino communities. The Chicano movement was gaining increasing momentum, the first Latino Arizona governor had just been elected, and numerous grassroots movements aimed to spark political change in Latino communities around Arizona.

“I did everything,” Falcon said. She knocked on doors, organized civic engagement events, and even transported art from California to Arizona for an ASU event.

‘Letting everybody know we’re here.’

Elizabeth Chavez, a 32-year-old mother of two who immigrated to the United States from Peru, does all she can to nurture a culture of voting in her family.

On most week nights, she drives her two sons to soccer events.

“I want them to remember always that I was there: raining, cold, hot, it doesn’t matter,” she said one recent night at the Benedict Sports Complex in south Tempe.

Tall, bright lights illuminate the soccer field where Chavez’s sons play. The complex is a soccer hub. Musky cleats thump against crisp grass. Whistles blow. Parents cheer.

“When I see them getting prepared in practice I (get) a good feeling that I’m doing something good for them, that I support them, and as a mom I’m giving my 100 percent to be there for them,” Chavez said.

She encourages them to be physically active, but also wants them to be politically active.

“It’s the only way we can let everybody know that we’re here,” Chavez said.

“There’s a lot of stuff we have to do for the Latino community,” she said, and the only way to accomplish that is for “the people who run this country know that we can make a difference by voting.”

Chavez said she arrived in the United States with her father in 1997 when she was 14 and began living independently at 15 because her father was unable to stay with her. She said she worked three jobs – at a warehouse, at a grocery store and as a waitress. She sent money back to her mother and siblings in Peru. She learned English on her own by reading as much as she could.

Chavez’s early life as an immigrant did not include any formal education, she said.

She talks to her two American citizen sons about politics, even though they are not yet old enough to vote. By voting herself, she is promoting a culture of civic engagement.

She votes, she said, because she wants “a better future” for her boys.

Changing the voting culture

Viri Hernandez drove her bright red Toyota sedan with another canvasser through west Phoenix neighborhoods with a large Latino presence.

They had already visited these homes from three to seven times since August to remind voters to mail in their ballots. But other concerns often take precedence over voting – like figuring out how to pay the bills, take care of children and maintain households.

She stopped the car at a beige house. Rachel Leon, 46, a stay-at-home grandmother, told Hernandez she hadn’t filled out her mail-in ballot. Hernandez answered Leon’s questions about the propositions, and explained how to draw a line to connect the arrow with the candidate of choice on the ballot. Sometimes, Hernandez knew, if voters don’t understand how to draw the line, they will write in candidates instead.

Leon filled out her ballot just as the mailman passed through her street. Hernandez carried the ballot out to him.