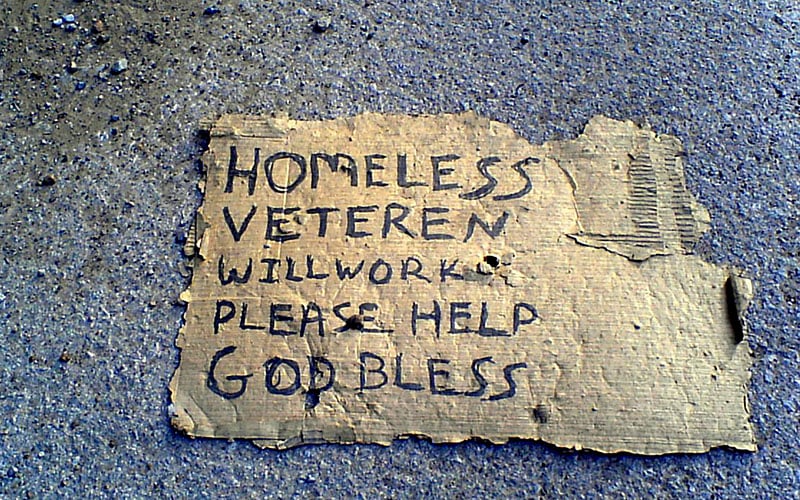

Veterans treatment courts divert vets who have been charged with a crime and connects them to services. The programs can cut repeat offenses and veteran homelessness sharply, advocates say. (Photo by anOnymOnOus/Creative Commons)

An Army veteran salutes the flag during a Memorial Day ceremony. Experts say Veterans Treatment Courts can help troubled vets stay out of jail by treating underlying problems they may have. (Photo by Lance Cpl. EmmanuelRamos/Marine Corps)

WASHINGTON – The way Gregg Maxon sees it, veterans have a hard enough time as it is when their service is done – they don’t need jail time added to the list.

Maxon is one of many advocates for veteran treatment courts, a diversion program that takes vets who have been charged with crimes and tries to keep them out of jail while getting them treatment for their underlying problems.

The courts – there are 436 around the country and 13 in Arizona – were praised this week by Veterans Affairs Secretary Robert McDonald, who cited them as one possible solution to the problem of opioid and prescription drug abuse.

“We owe it to the nation’s veterans to help them end their dependence on opioids and break the downward spiral that all too often ends in homelessness, prison, or suicide,” McDonald said during an event Tuesday with officials from the Justice Department and the White House. “But we can’t do it on our own.”

The first Veterans Treatment Court opened in Buffalo, New York, in 2008 and Arizona’s first opened a year later with the Veterans Treatment Court in the Tucson Municipal Court system.

Unlike other diversion courts, veterans are offered “unique benefits” through the veterans court program. Maxon, judge pro tem for the East Valley Regional and Mesa Courts, said the programs deal with the “underlying conditions” that caused the problem that brought the vet to court.

-Cronkite News video by Dillion Eddie

“We also try to get them connected with other services,” Maxon said. “For housing, for employment, for disability compensation – we try to get them connected with their service-earned benefits.”

Upon completion of the treatment program, Maxon said charges against the vets could be “reduced to a lesser charge or, in some cases, their charge may be outright dismissed.”

The number of courts is increasing rapidly, jumping from 351 in 2014 to 436 last year, according to a report from Veteran’s Affairs.

McDonald said they have helped thousands of veterans in a few short years. He pointed to statistics that show 88 percent of veterans who go through a program see a reduction in arrests and 30 percent are more likely to be in stable housing in the year after they complete their treatment.

The program is not easy for those veterans who do participate, said Maxon, adding that they “are not a free pass.”

“They (veterans) are still held accountable for their conduct,” he said, but court officials use “treatment and therapy to stop their behavior and stop their criminal behavior cycle.”

Jeff Singer, a judge for the Veteran Court in Kingman, agreed that the “program’s not easy.”

“The participants of the program have to come to court numerous times and they have to abide by a lot of the terms and conditions of the program, including sobriety and counseling,” Singer said.

Kingman was one of the most recent courts to open in Arizona, beginning operations in December – and graduating its first veteran this month. Singer said Kingman has 10 participants in its court and is “growing at a decent rate.”

“I just think they’re wonderful because it gives veterans who’ve served their country a second chance,” Singer said of the courts.

Veterans who go through the program, he said, are “in a lot better place in life when they graduate the program than when they first entered into the program.”