TEMPE — “The vault” is a climate-controlled room that sits behind three locked doors in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University. Housed inside are fifteen charcoal-colored pebbles that collectively weigh less than a quarter of a pound.

Make no mistake: these are no ordinary rocks.

Related video:

They are the remnants of a roughly 4.5 billion-year-old meteor that streaked across the Phoenix sky earlier this month.

Laurence Garvie, research professor and curator at the Center for Meteorite Studies, knew something big had happened when videos of the meteor sighting appeared on social media early on June 2.

“The question that was in our minds was ‘Is there something on the ground?'” he said.

Although finding any meteorite is rare, finding one so soon after a fall presents scientists with an even more unique opportunity.

“Most of the meteorites we have in the collection—they sit in the desert for hundreds of thousands of years,” Prajkta Mane, a doctoral candidate at the center, said. “This (finding) is very pristine.”

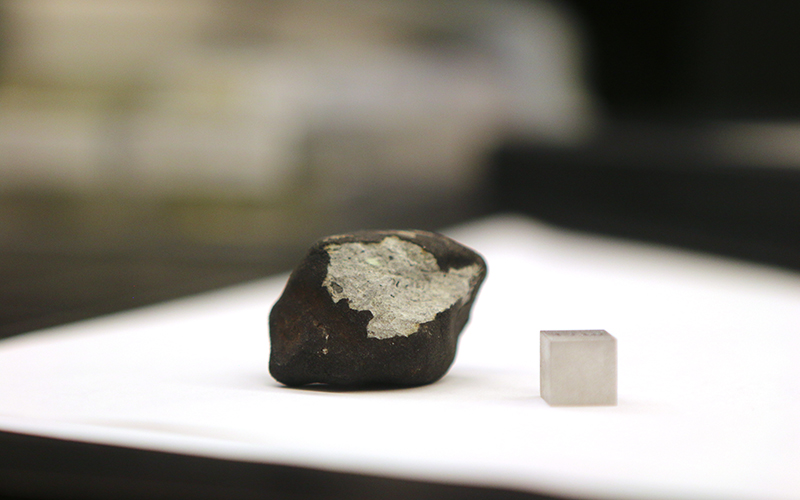

Pieces of the meteorites will be encased in epoxy and prepped for geochemical analysis. (Photo by Anna Copper/Cronkite News)

Doppler radar indicated a possible strewn field on the White Mountain Apache Reservation in the eastern part of Arizona. The sooner scientists could begin searching the area, the better.

However, because the remnants fell on tribal land, the meteorites technically belong to the White Mountain Apache tribe.

ASU negotiated with the tribe, and just three weeks after the initial sighting, they reached an agreement to allow Garvie and his team to come out and search the area.

“This is a really special union here,” said Daniel Dunlap, also a doctoral candidate at the center. “The tribe had no reason to let us come there, and this is very sacred land to them. They don’t go on it. They don’t let other people go on it. It’s theirs by law to protect as they see fit, and they were nice enough to let us come out and look for (the meteorites).”

– Research professor Laurence Garvie

Garvie gathered his team, which included Dunlap and Mane as well as three professional meteorite hunters, and together they made the four-hour trip to the reservation and continued another two hours on a dirt road to reach the search area.

They spent four days and three nights in a remote mountainous landscape, canvassing an area roughly eight miles in length by half a mile wide and avoiding bumping into prickly cholla. Garvie said they spent most of that time staring at the ground looking for any traces of little black rocks that “just look different from everything else.”

“You just have to keep walking and walking and walking and just by chance you come around that little bush on the ground and there it’s sitting on the ground—but most of the time it isn’t,” Garvie added with a smile.

But that first afternoon, they were in luck. Within the first half hour, one of the meteorite hunters found the first pea-sized stone. Garvie said that the find changed the game plan immediately. They knew they were in the right. They just had to track down the rest of stones.

They returned to Tempe with a total of fifteen small meteorites, which are now encased in individual plastic boxes back in the vault.

The fifteen meteorites recovered from the White Mountain Apache tribal lands. (Photo by Anna Copper/Cronkite News)

The next step will be to classify the meteorites by analyzing the different types of minerals in them. Then they will be named and logged into a public database.

Since doppler radar data suggested there are more, possibly larger, meteorites yet to be recovered from the fall, Garvie considered this first trip to be merely reconnaissance.

Negotiations between the university and the tribe will continue as they work out further agreements to determine the extent to which Garvie and his team can study the meteorites. Should they get permission to move forward, they hope these findings will help them better understand what our early solar system was like.

Another perk, according to Garvie?

“We get to study it first!”

Inside “the vault”

Inside “the vault”