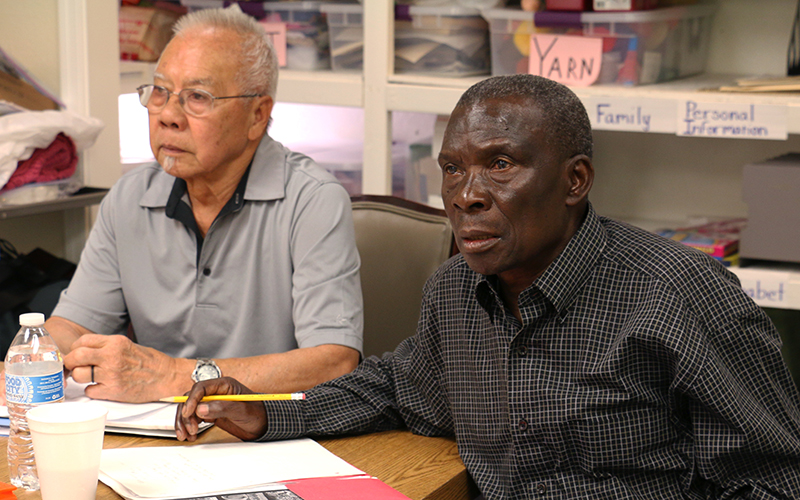

Leonce Gaternya, a former refugee, attends the Mosaic Senior Center on April 19, 2016 in Phoenix, Arizona. (Photo by Kaitlyn Ahrbeck/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Building a new life can be difficult enough for a young refugee. It’s even harder for an elderly person to learn a new language and culture while coping with displacement and loss.

Since 2013, there has been a continuous increase in refugees in Arizona from Burma, Congo, Syria and Burundi. At the same time the number of refugees from Iraq and Cuba has fallen. Overall, refugee arrivals in Arizona increased about five percent in 2015, according to the reports from Office of Refugee Resettlement.

Violence forced Leonce Gaternya, 68 to flee his home in Burundi. “At the time, all my family was killed,” said Gaternya. “My father and my siblings, I lost them during the war.”

In 1972, a violent genocide erupted in Burundi where the Tutsi-dominated government killed hundreds of thousands of Burundians.

Thousands more fled to refugee camps in neighboring countries including Tanzania and the Congo to escape the violence. Gaternya and his wife Salome Kazobagora were among those refugees who escaped to the Congo.

In 1995, after living in the Congo as a refugee for 35 years, Gaternya left with his family to seek refugee status in Tanzania. They remained there for the next 11 years.

“In Tanzania, even though I was recognized as refugee, my family and I had many problems. We were not allowed to live in the city,” said Gaternya. “But thanks God the United States allowed people who left their country in 1972 to have resettlement services.”

In September of 2007, after several interviews, Gaternya and his wife were granted resettlement in the United States.

“God helped us to resettle here where services were available,” said Gaternya.

The International Rescue Committee helped the family with the resettlement process. The agency told Gaternya and his wife to come to the U.S first and then shortly after their daughter would also be allowed to join them as part of the family reunification process, according to Gaternya.

Nine years later his daughter, now 41 years old with three young children, is still stuck in Tanzania. Separation of family members is among the many struggles that elderly refugees face.

Coping with trauma, loss

The couple found help adapting to life in Phoenix from Mosaic Elder Refugee Program.

“We have case managers who serve clients from war-torn countries,” said Jolie Mbonyingabo, director of the elderly refugee program.

Refugees at the center come from a multitude of different countries and speak a diverse number of languages. Most of the refugees are from Afghanistan, Bhutan, Burma, Burundi, Cuba, Congo, Iraq, Syria and Vietnam.

Hernan Suen Tan (left) and Leonce Gateranya attend an English lesson at the Mosaic Senior Center on April 19 in Phoenix. (Photo by Kaitlyn Ahrbeck/Cronkite News)

The center helps clients with questions about housing, healthcare and social services, but the biggest focus is helping elderly refugees gain citizenship, according to Mbonyingabo.

“Learning opportunities here are very good. We have the opportunity to learn English here at the area agency,” said Gaternya. “I and other seniors from my country don’t know how to read and write, but we have been exposed to learn how to write.”

It’s a fairly frequent occurrence that elderly refugees come to the center without being literate.

“We estimate that like 84 percent of our clients are pre-literate,” said Andria Cubero, Americorps Vista coordinator with the elderly refugee center.

A pre-literacy program at the center helps refugees who don’t have reading and writing skills.

“We don’t shut anyone out from coming to the pre-literate classes over and over again because with these older individuals they really struggle to pick up new knowledge,” said Cubero. “That combined with their age means that they are not able to jump into traditional English as a second language classes with their peers.”

“Right now, I can write from one to ten. Now I can even write and read the alphabet,” said Gaternya.

Elderly refugees also struggle with mental health issues, according to Trinh Vu, a case manager for the Asian refugee population

She says the majority of the elderly refugees at the center suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, depression or other related conditions.

The path to citizenship

The refugees are allowed benefits for seven years after they arrive in the U.S. But unless they have passed their citizenship test, they are no longer eligible to receive medical care.

Refugee must pass a civics test and be able to answer questions in English during an interview in order to become citizens.

Gaternya became a U.S. citizen this year on January 22 after nine years in the U.S. as a refugee.

“I’m so grateful for the opportunity this country has given me to become a U.S. citizen,” said Gaternya. “From refugee status to U.S. citizen, I am very happy about it.”

But his case is rare. Most refugees struggle to become citizens. According to Vu, about 85 percent of the center’s clients are not able to pass the U.S. citizenship test.

An alternative to the citizenship test is receiving a medical waiver. However, it can be difficult when refugee patients are not willing to disclose their information to the doctor, said Vu.

“They don’t feel safe to disclose information,” Vu said. “They are afraid to talk.”

Vu explains that most of the elderly refugees have spent years, even decades, in camps or jails and have had to deal with corrupt government officials.

‘A place where we can go’

Many elderly refugees cope with feeling alone in a new country.

“Because of their age, they are isolated at home,” said Mbonyingabo. “Their family, their children go to work and they are left at home alone. So we provide transportation to bring them to the Mosaic Center to have activities, socialization.”

“I have friends here in the United States, my friend comes to visit me at my apartment, we share food,” said Gaternya. “We do talk and even though sometimes it’s very hard for me to know what my friend is saying, but my grandkids help me with interpretation.”

“I am a farmer, that’s my life,” said Gaternya. “I have been a farmer all my life, but when I get up in the morning I just take a shower and then I sit there.”

“My wish for the other elderly people from my country is to have some kind of activities, gardening opportunities, a place where we can go and do something just to get involved,” said Gaternya.

Despite the challenges, the help adapting to his new life has made all the difference.

“There is nothing I can say, no words to express my gratitude towards the services that I benefit from at the Area Agency on Aging,” said Gaternya.

And though he’s grateful, something is missing.

Gaternya has relentlessly tried to bring his daughter to the U.S. He’s even written letters to the Office of Refugee Resettlement in Washington, D.C.

“Washington told me to get in touch with my daughter and ask her to seek asylum there in Tanzania,” said Gaternya. “But still today there is no answer.”