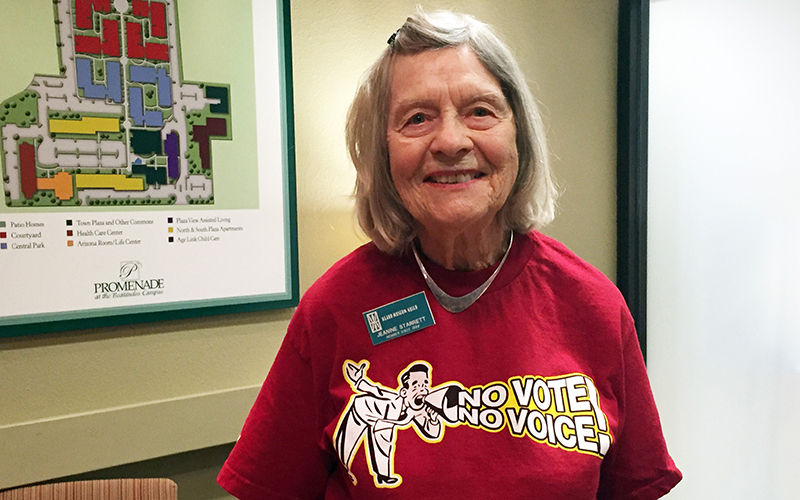

Jeanine Starrett, a 50-year member of the League of Women Voters, at Beatitudes retirement community on Arizona’s primary day in March. (Photo by Lily Altavena/News21)

PHOENIX – Loretta O’Malley has been voting since she was 21-years-old. Even in Okinawa, Japan in the 1950s, she cast her ballot while serving in the U.S. military.

But this March, O’Malley did not vote in Arizona’s presidential preference election. Faced with massive lines snaking around the two different polling places she visited, the 83-year-old with a heart condition and a bad back turned around. She knew she could not physically stand for that long.

“I have never missed voting,” she said, still frustrated.

Long lines in Maricopa County were only one of the obstacles facing some of Arizona’s 65-and-older prospective voters. Senior voters said they also struggle with ID requirements and finding information on the process. In a state where almost 13.8 percent of the population is over the age of 65, according to U.S. Census data, these barriers can be significant.

The number of polling places in Maricopa County was slashed from more than 200 in 2012 to 60 in 2016 for the presidential preference election, and many of those eliminated were popular with senior citizens.

The number of polling places at community centers – often central to senior activity – was cut from 25 in 2008 to 10 this year. For example, 84-year-old Sonja Collier would have usually voted at the Contempo Tempe mobile home park, which caters to retirees, but it did not appear on this year’s list.

Instead, she went to Pyle Recreation Center in Tempe, where it took her two hours and ten minutes to vote in the presidential preference election. Collier, who recently detailed her own voting experience before an afternoon bingo game at Tempe’s Cahill Senior Center, also has a heart condition.

“It was horrible because I can’t stand up,” she said of the long line. “I wouldn’t want to do it again.”

Though the Maricopa County’s Recorder Office offered shortened wait times for people with disabilities, some seniors said they weren’t offered the option. Collier said two women standing near her helped keep her spot in line as she found different places to rest.

Pam Koester, executive director of Leading Age Arizona, said the reduction in polling places was felt by her organization’s network of local, non-profit agencies serving the elderly, including local retirement communities and nursing homes.

“Many of our (locations) would be the polling places for the community,” she said. “Which was really great because the residents were right there and could go and vote right there in the community.”

In the cities of Sun City and Sun City West, the number of polling places was cut from 15 in 2008 to one in Sun City West this year. More than 74 percent of the residents in both cities are 65 and older, according to census data.

Although county officials offered early voting as a solution to long lines, not every senior believes in mailing in a ballot. In Cochise County in the southern part of the state, 63 percent of in-person voters were over the age of 55, county election officials said.

“I don’t care for absentee ballots so I vote personally,” said Billie Foltz, a resident of the Beatitudes retirement campus in Phoenix. “A lot of things could happen to the absentee ballots.”

Arizona’s voter ID requirements, too, can sometimes impede a senior’s ability to vote, according to Lori Smetanka, the executive director for the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care.

Because some elderly Arizonans will give up their driver’s licenses when they stop driving, staff members at the Beatitudes retirement campus in central Phoenix organize an annual trip for residents to get permanent state identification cards, said Barbara Wood, the campus’ director of development.

“Many older residents may not have or know where their social security cards are, for example, or may not be able to access birth certificates because record-keeping is different or they may have moved,” Smetanka said.

But even after securing identification, elderly voters might still face registration problems and confusion – especially when a lot of information is online.

Ray Collins – who did not share his age like many of the seniors interviewed – is registered, but was confused about policies barring independents from voting in presidential preference elections. He said he wished election officials mailed out material explaining state procedures.

“I can’t get any information,” he said. “I haven’t got a darn thing.”

Barbara Lindsey, at Tempe’s Cahill Senior Center, moved to the state a few years ago, but to her frustration, has not been able to register. She said she attempted to register at a local library, but was turned away because it did not have registration forms.

Helping elderly voters or those in nursing homes may come down to just a little more patience and accommodation, Smetanka said. “There should be a recognition and awareness that there is this population that needs additional assistance to exercise their right to vote.”

Jeanine Starrett, another Beatitudes resident, is a 50-year member of the League of Women Voters. By late afternoon the day of Arizona’s primary, she said she had already helped at least three people vote, directing them to the closest polling place.

Starrett said the slogan she proudly wore emblazoned on her bright red t-shirt explained why voting is important for everyone:

“No vote, no voice.”

Editor’s note: This story was produced for Cronkite News by the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Voting Wars” national reporting project.