ELOY – Experts said Arizona’s mild weather and clear skies make the state an ideal area for skydivers. Tourists, military personnel and national skydiving teams from around the world travel here to train.

Arizona has eight U.S. Parachute Association affiliated drop zones. Skydive Arizona, the largest drop zone in the state and one of the largest in the world, sees between 110,000 and 150,000 jumps a year.

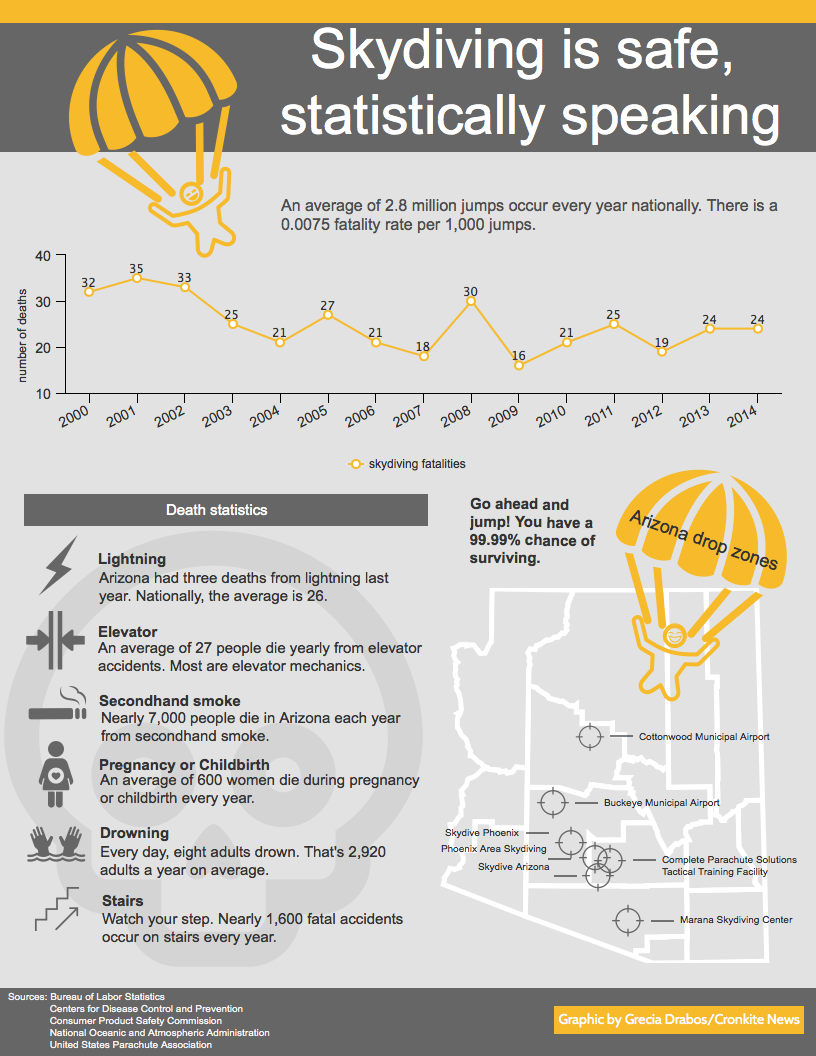

Skydive Arizona safety expert Bryan Burke said he doesn’t have exact numbers for his facility year over year. However, skydiving nationwide has been on an upward trend over the past couple decades because of safer equipment and the ease of access into the sport, Burke said.

Jumps have been increasing nationwide since 2006, according to the parachute association website.

But even popular jump sites like Skydive Arizona see their fair share of incidents. From late December 2015 to early February 2016, three skydivers died at the Eloy-based facility.

“We’re dealing with a fairly small statistical pool, but to have three in few weeks like we did is pretty much unheard of,” Burke said.

Still, the fatalities haven’t slowed down business, Burke said in an e-mail. Individual beginning skydivers pay upwards of $179 to do a tandem dive.

While the first fatality is still under investigation, Burke attributed the other two to the most common reason skydivers have accidents: going into a turn too fast and too close to the ground.

“If you compare it to driving cars, we know what gets people in car wrecks. And prevention is the hard part,” Burke said. “People still go too fast, don’t look where they’re going. It’s the same thing year after year.”

As the safety expert, Burke said he responds to accidents at the facility and files reports to the Virginia-based parachute association, the sport’s national governing body, which keeps the classified information for statistical and educational purposes.

Burke said one skydiver who died recently caught his parachute on his GoPro camera, while the other was using a high-performance parachute he was not trained on or prepared for.

“Point of view cameras are a serious concern as far as entanglement problems,” he said.

“Almost all skydiving accidents can be attributed to operator error,” Burke added. “I would say upwards of 80 percent of it, skydivers equipment is operating properly and then they mishandle an emergency.”

In 2015, there were an estimated 3.2 million skydive jumps in the United States, said Nancy Koreen with the parachute association. Of the 21 fatalities in 2015, 13 held a “D-license,” the most expert license a skydiver can achieve. The license requires a minimum of 500 completed jumps. Student skydivers made up three of the deaths nationwide.

“With the student program, we’ve never had a serious accident,” Burke said. This is because instructors watch students closely, he said.

The company checks every visiting diver for credentials and equipment, but the facility cannot control for human error, he said. Skydiving is one of the few sports regulated by the federal government. The Federal Aviation Administration has standards parachuters have to meet.

Melissa Lowe, an expert skydiver and instructor at Skydive Arizona, said building a proper foundation from the beginning can eliminate a lot of risks in skydiving.

“In my education growing up in skydiving, I was part of the phase of watching skydiving maturing as a sport,” she said. “We went from really experimenting to perfecting techniques and being able to train those techniques to the new students of the sport. I try to convey the safety.”

There is a psychological factor that goes into skydiving safety as well, said Lynda Mae, a social psychologist and psychology lecturer at Arizona State University.

“Statistics actually show you’re more likely to die while driving or playing football than you are with skydiving,” Mae said. “What’s true is that people have a different perceived risk of skydiving.”

After every successful completion of a task, the fear factor goes down, Mae said. This idea can be applied to skydivers as well.