SCOTTSDALE — An NFL Network video shows David Baker, president of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, walking the halls of the Stanford Court hotel in San Francisco the night before Super Bowl 50. He knocks on the door of Kendra Stabler Moyes’ room.

“I know it has been a long journey, and I wish he was here, but your dad’s going to be in Canton, Ohio, in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Forever, ” Baker told her.

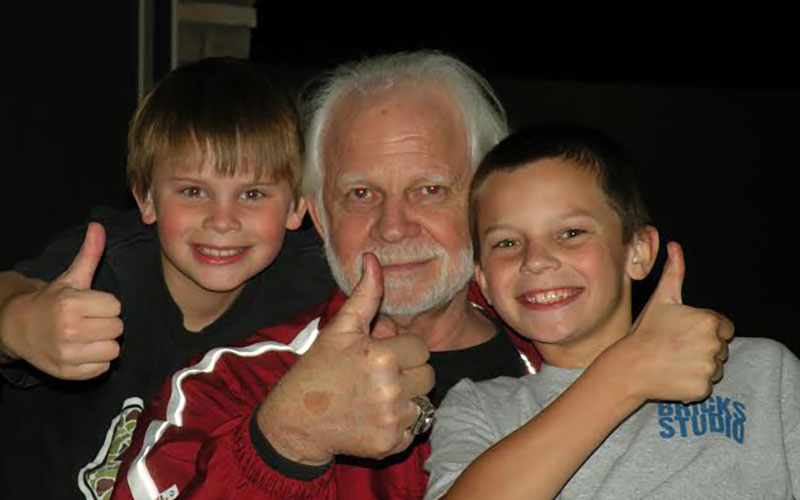

Stabler Moyes’ father is Ken “the Snake” Stabler, the legendary quarterback whose journey included stops in Alabama, Oakland, Houston and New Orleans during his playing career, and Arizona after it was over. At the end, he fought cancer and traumatic brain injury, a battle his grandsons Jack and Justin helped him fight until his death in July.

Justin and Jack, twin brothers, both play football for Chaparral High School in Scottsdale. With his health declining in 2014, Stabler wanted to be closer to the boys and their mother, so he moved to the Valley and spent his final year in Arizona with the people who made him happiest. All while trying to fight off the cancer that was slowly killing him.

“That’s all he would talk about in the years and years leading up to it, because he just wanted to be near them,” Stabler Moyes said.

Eight months after his death, the world found out what his family had already suspected: Stabler suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, otherwise known as CTE.

Stabler had decided to donate his brain to Boston University’s CTE Center after watching the coverage of former Chargers linebacker Junior Seau’s suicide in May 2012.

Dr. Ann McKee, professor of neurology and pathology at Boston University, examined Stabler’s brain and diagnosed him with CTE. According to the Concussion Legacy Foundation, Stabler was the seventh quarterback and the 90th of 94 former NFL players whose brains were examined at Boston University and found to have CTE.

McKee appeared at a congressional committee roundtable on concussions Monday where an NFL official acknowledged a link between football and CTE for the first time. According to video of the meeting, Rep. Jan Schakowsky, D-Illinois, asked Jeff Miller, the NFL’s senior vice president for health and safety, if he believed there was a link between football and brain disorders like CTE.

“Well, certainly, Dr. McKee’s research shows that a number of retired NFL players were diagnosed with CTE, so the answer to that question is certainly ‘yes,’ but there are also a number of questions that come with that,” Miller said.

Schakowsky repeated the question, “Is there a link?”

“Yes. Sure,” Miller responded.

Tuesday, NFL spokesman Brian McCarthy released a statement to multiple media outlets, including PBS’ Frontline, saying, “The comments made by Jeff Miller yesterday accurately reflect the view of the NFL.”

For years, the league had disputed the claim that there is a link between football and CTE, a condition with symptoms that can appear well before death, but can only be diagnosed post-mortem.

“CTE is way down the road in regard to traumatic brain injury,” Dr. Steven Erickson, medical director of the Banner Concussion Center in Phoenix said. “CTE is a diagnosis based on multiple poorly treated or untreated head traumas in a genetically susceptible individual that results in neurodegenerative disease. We believe there is a genetic component to the long-term damage resulting from sustaining multiple concussions.”

Now the Moyes’ boys must live with this burden playing the sport their grandfather loved. But they must also decide if they will allow the Stabler legacy on the gridiron to continue and allow their own children to play football.

“Everyone who plays the game knows there is a risk factor,” Justin said. “That’s what comes with it and you can’t play thinking about it but I mean it is there and it happens to everyone.”

“It’s only going to get safer,” Jack added. “They’re going to teach you how to hit.”

For a period of time, Justin and Jack, whom Stabler referred to as his “grandsnakes,” lived with him after he moved to Arizona.

“He would wake up and make them smoothies and do their laundry. They weren’t driving at the time so he would bring them lunch. It was super cute to think he was like their little nanny,” Stabler Moyes said.

He left Justin, a receiver, his Super Bowl ring, and Jack, who plays defensive back, wears his grandfather’s Alabama national championship ring around his neck. While living in Arizona, their grandfather didn’t miss a practice or a game of theirs.

“Looking up and seeing him in the stands was always fun because he had always lived across the country,” Justin said. “When he moved out here, we were super grateful to have him attend every game. I’m really glad he did that right before he passed away.”

Chaparral honored Stabler last fall before a Sept. 26 game against Mesa Red Mountain. Chaparral won in overtime.

Their grandfather’s legacy may seem like a lot for Jack and Justin to live up to, and he gave the boys occasional tips, but there was never any pressure to play quarterback like their grandfather.

“He said, ‘Find your position and let your coaches put you where they want to see you,'” Jack said.

When Jack and Justin were younger, Stabler Moyes said her father visited the Valley and often came to Grayhawk Elementary School in Scottsdale. He sat with the boys in the lunchroom and then went out to recess and threw the football around, even taking off his national championship and Super Bowl rings to let the kids try them on their fingers.

Stabler was content to share a lot in the early years of his retirement but became more reserved when his health began to deteriorate.

There were a lot of things left unsaid in the Stabler household due to the Foley, Alabama, native’s personality. A private man, according to Stabler Moyes, he knew he had prostate cancer and received treatment for three years at M.D. Anderson Hospital in Houston before he told his three daughters about his diagnosis.

It wasn’t until early 2015, when Stabler found out he had stage IV colon cancer, that his family found out about the prostate cancer as well.

“It took a while to digest that,” Stabler Moyes said. “We didn’t have a lot of time to deal with it. He wasn’t one to talk about himself. He obviously knew what was going on with him way more than what we did because he was very private and didn’t want anybody to worry about him.”

It wasn’t just his body. Stabler’s mind also began to fail him.

In his final days, as he watched his grandsons play the game he loved, Stabler was also constantly reminded of the toll the game took on his brain, Stabler Moyes said.

“I’m sure it was really tough for him to be at the football games because there were times when lights would trigger stuff,” she said. “The fans and all the noises and the clapping. That definitely affected him, but he would never say anything.”

When Stabler would reminisce about his days with legendary Alabama coach Bear Bryant or Raiders’ coach John Madden, Justin and Jack noticed their grandfather retelling the same stories over and over again. Once while driving his grandsons to school, he stopped the car at a green light.

“As I got older, I started to pay more attention to that kind of stuff,” Justin said. “You could kind of see that in everyday life. You could just see that he was really mentally foggy.”

It continued to get worse. It bothered him to hear dogs barking. He had ringing in his ears.

“He wouldn’t have outbursts of anger or do crazy things,” Stabler Moyes said. “I’m grateful to an extent that it didn’t get to a point where you read about some of these players and how bad it gets for them and their families.”

He also joined a class-action lawsuit of former players against the league that is currently under appeal.

For Stabler, it wasn’t about the money.

“He joined it (the lawsuit) because he wanted to be supportive and help other players and to be another voice,” Stabler Moyes said. “He just wanted to help those guys who were struggling.”

In March 2015, as Stabler continued to struggle, he left Arizona and moved to Gulfport, Mississippi, to fight the disease near his home state of Alabama, with his partner Kim Bush by his side.

Fourth of July weekend came around.

“He was doing really well and he just kind of took a turn,” Stabler Moyes said.

He died July 8 in a Gulfport hospital listening to a love song about his home state, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama.” He was surrounded by Bush, Stabler Moyes and her two sisters, according to Stabler Moyes.

“If you had to go, it couldn’t have been more peaceful and nice,” Stabler Moyes said. “He was just his sweet, goofy, happy self until the day he died.”

The concussion crisis in football will continue to unfold, but a long chapter in the book on Stabler will soon close after an extended candidacy for the Hall of Fame.

The 1974 NFL MVP led the Raiders to the Super Bowl XI title and five straight conference title games. He threw more interceptions than touchdowns in nine of his 15 seasons, but only had one losing record on notoriously bad knees. while twice leading the league in touchdown passes and completion percentage.

He was a finalist for the Hall of Fame in 1990, 1991 and 2003. But it took 13 more years – almost a full year after his death – to finally get a bronze bust in Canton.

“It was obviously very frustrating because, you know, why right after he died? Why not before?” Stabler Moyes asked. “If he was good enough to go into the Hall of Fame this year, he should have been in there right after he retired.”

She still remains grateful for the honor and said it’s something the family will cherish. But Stabler himself never lost sleep over being slighted while he was alive.

“He would always say, ‘It doesn’t change the way I put my socks on tomorrow,'” she said. “I always thought that was really cool because it was just never a big discussion in our family.”

On what will likely be a sticky August evening in Canton, Stabler’s family still plans to celebrate with that full knowledge of what football can do to a man. They’re not interested in living in fear of what might happen, the same way their father and grandfather approached his own life.

“We’re not just going to sit like it’s a funeral,” Stabler Moyes said. “We’ll try to party like he would have wanted and be happy because that’s what he would want.”