A computer used to find books and media at Litchfield Park Library on April 18, 2024. Integrating artificial intelligence into library services may change the way information is retrieved and categorized. (Photo by Kayla Mae Jackson/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Librarians have a lot to think about now that artificial intelligence has entered the picture. Not only could the technology fundamentally change the way they do their jobs, but it also affects areas such as patron privacy and information literacy.

But librarians also see AI’s potential for good. Cataloging and research are major areas in librarianship that artificial intelligence can automate and potentially improve.

The promise of AI in libraries

Kira Smith is a librarian who works with Ask a Librarian, a Florida-based virtual reference service where local residents can connect with librarians via text message, live chat or email. She said that some AI tools, like chatbots, can answer common questions from patrons, easing the workload on librarians.

“If people want to know what time the library is open, a chatbot can easily answer that, which would then free me up to answer the longer questions,” Smith said.

Integrating AI into library services may also fundamentally change the way information is retrieved and categorized.

Nicole Hennig, an e-learning developer at the University of Arizona Libraries, said AI can help with keyword search, a method where a user types the most relevant words of a topic or question into the search box of a database. Specifically, it can generate keywords users would not have otherwise come up with.

But Hennig said libraries may transition to a new type of technology called semantic search, which draws from the meaning of the words in a search to find results. By contrast, keyword search results contain direct word matches or related words.

“Libraries have always been about adding keywords and subject headings … and then applying them to things so that people can find them. That’s been since the beginning,” she said. “But semantic searching is more about using the statistical math behind these models that can know what objects are similar to each other conceptually.”

Hennig said a shift to semantic search will be slow and that it wouldn’t fully replace traditional cataloging techniques. But if libraries do use it, she said, it can be a net positive.

“There will always be some need for cataloging and adding tags and things for some collections – maybe just not everything. And it will help us make stuff available that we don’t have the labor to make available now,” she said, noting semantic search lets researchers find sources that don’t have certain keyword tags.

The changing role of librarians

Computers are available for library guests to use at Litchfield Park Library on April 18, 2024. (Photo by Kayla Mae Jackson/Cronkite News)

Martin Frické, University of Arizona professor emeritus and author of “Artificial Intelligence and Librarianship: Notes for Teaching,” said that historically, librarians have acted as intermediaries between patrons and needed information. AI tools may change that.

Perplexity, for example, is an AI-powered search engine that can generate answers to research questions, search for sources and summarize articles.

“If you’ve got something like Perplexity on a grand scale, often you won’t need a librarian at all,” Frické said. That’s why he said librarians will need to adjust their intermediary role.

This isn’t the first time libraries have dealt with disruptive technology, though, and librarians can look to the past to prepare for the future.

“When the search engine started to have a big impact, more than a few librarians – and particularly the reference librarians – became absolute experts at using Google search,” Frické said. “They’re completely on top of Boolean search and things like that, which a lot of ordinary people just don’t understand.” Boolean search is a technique where a user enters terms such as “and,” “or” and “not” to get the exact results they want.

Frické said it’s possible for librarians to transform from experts in regular search engines to experts in engineering prompts for large language models. That way, librarians could be a go-to resource for researchers wanting to find information using AI.

AI and patron privacy

Hennig said the main way libraries access any new technology is through large vendors, which are already looking into adding AI into their services.

“I’m sure that … whatever vendor we have, they’re going to come to us and say, ‘Do you want to be a beta tester? Do you want to test this natural language search thing that we have?’” she said. “And we can try it and decide whether we want to include it.”

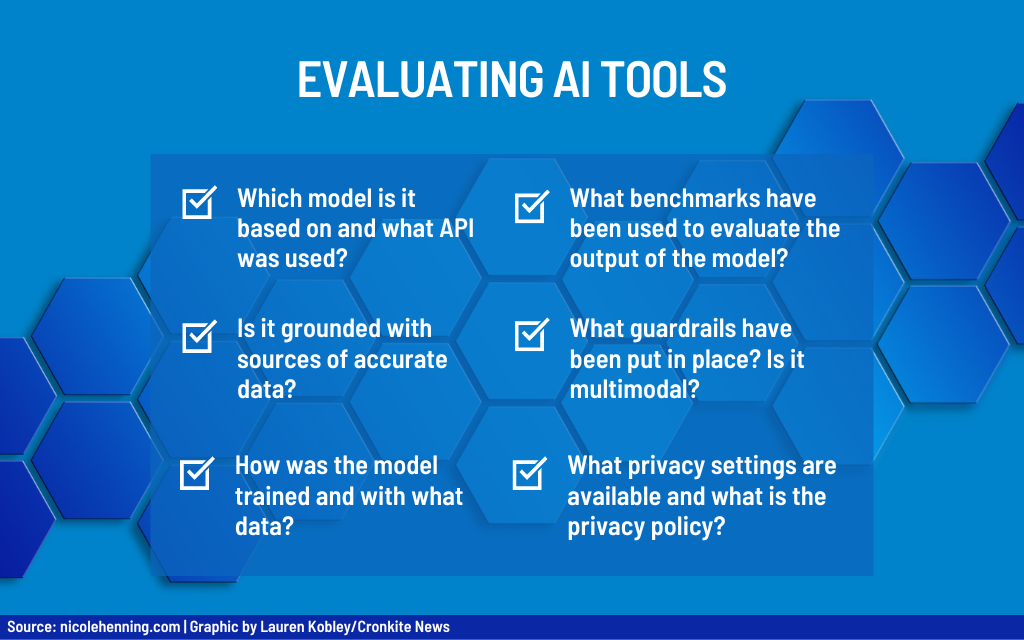

There are several factors librarians must consider when deciding whether to purchase a service.

One of them is patron privacy, which is a top priority for librarians like Smith.

“I think that it’s important to protect patrons’ privacy because it’s nobody else’s business what you like to read,” Smith said. “So I would think long and hard before sharing that kind of circulation data with any sort of AI or other system.”

According to a guide Hennig created for librarians to evaluate AI tools, privacy policies – which tell users what information about them is collected and how services use that data – are important to take into account.

Information literacy considerations

AI is transforming another important area: information literacy. Those who are information literate are able to identify when information is necessary plus “locate, evaluate and use effectively the needed information,” according to the American Library Association.

“Now this area, information literacy, has almost been blown apart by artificial intelligence,” Frické said, pointing to deepfakes, hallucinations – when AI misinterprets data and presents something untrue as fact – and other errors attributable to the technology.

Henning said librarians have a role to play in keeping everyone up to speed.

“Because there’s such a big lack of awareness and because we already have done information literacy training for years now, this just kind of adds to it,” she said. “And we quickly need to learn about AI so we can include that in our information literacy training.”

Smith said that after finding out students were using tools like ChatGPT to write papers, she realized the importance of responsible use.

“That made me take seriously how this was going to impact the field and ways that we could use AI to be helpful to people but not have AI do all the work,” Smith said “So I think that for libraries and students, it can be used as a tool, not as a replacement.”