TUCSON – Suzanne Eckert leaned over the second-floor railing in the old Arizona State Museum building, now used for storage after the museum outgrew the space years ago.

“This is one of our storage rooms,” said Eckert, the museum’s head of collections. In front of her, stacked 10 high, 12 wide and at least 40 deep were boxes of material from past archaeological digs.

It’s the haystack in which museum researchers must find thousands of very special needles – the human remains and “funerary objects, sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony” it acquired over decades of government-sanctioned and commercial looting of Native American graves.

Tribes say law requiring return of remains, relics, hasn’t met promise

The journey home: Tribal officials discuss importance of repatriation

The museum, like all facilities in the country with Native American artifacts in their collections, is required by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act to return those remains and cultural items to the tribes from which they came.

It’s slow going.

As of April, the Arizona State Museum had issued notices of inventory completion for 1,095 human remains – a little less than half of its total collection of culturally identifiable remains.

Still, that’s better than most museums in the country, which collectively had more than 140,000 human remains left to be repatriated last year, according to the National NAGPRA annual report for 2014. That’s out of a total collection estimated at 180,000 human remains when the repatriation law took effect in 1990.

When NAGPRA was enacted, it came with a five-year deadline. Federal agencies and institutions that receive federal money, like museums and universities, were supposed to publish inventories of items they were holding that should be returned to tribes by 1995.

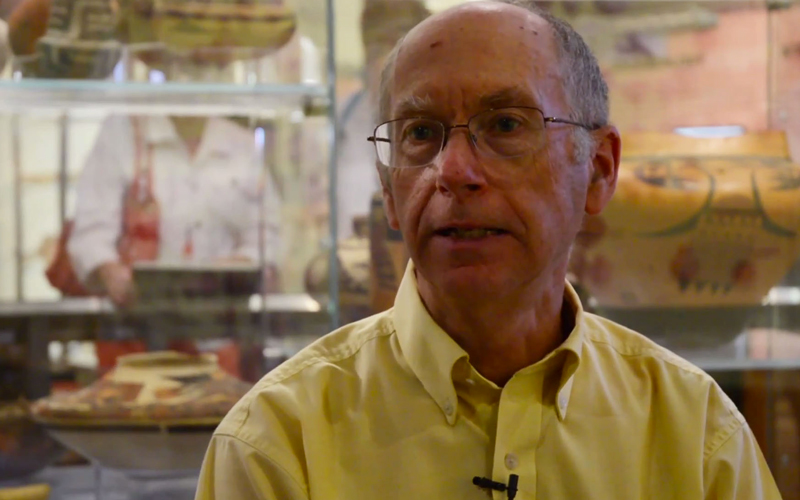

“Five years sounds like a long time, but for museums that have been collecting … for 120 years, they had very large collections,” said John McClelland, the Arizona State Museum’s NAGPRA coordinator.

McClelland, who began working with NAGPRA as a graduate student in 1995, said early archaeological digs were not well documented and museum inventories were kept on obsolete computer equipment that couldn’t be trusted.

Researchers had to take inventory by physically sifting through boxes of objects.

“We feel like we need to go back to the original excavation notes to find out what was originally reported, and then we need to track down all of those objects,” McClelland said. “There wasn’t enough time in those five years to do a physical verification of what was on the shelves or to do that kind of research.”

McClelland said the museum plans to finish the job in three years. That’s OK with Arizona’s tribes, which would rather have the museum do a thorough inventory in the next three years than run the risk of repatriating incomplete collections.

Despite many tribes’ frustration with the slow pace of the work nationally and with the refusal by some museums to return items they say fall under the law, advocates say the Arizona State Museum stands out as a model for how NAGPRA was intended to be carried out – researchers collaborating with tribes to return items as a measure of good will.

“We’re just all generally getting a better understanding of prehistory in America, and I think working with NAGPRA, it’s a really good way to bring the tribes and the researchers together,” said Melanie Deer, a curatorial and museum specialist at the museum.

The museum works closely with tribes in Arizona and nearby states to determine cultural affiliation of objects and human remains, and McClelland is well respected in the tribal community for his efforts to carry out their wishes.

McClelland said he treasures the relationships he has built working with Native American communities and said his work with repatriation has changed his view of archaeology.

“In the scientific profession, you tend to view bone as just that, as material that is inanimate that you would study,” McClelland said. “As a result of my continued work with repatriation and working with Native American communities, I really changed that attitude quite a bit to view human remains as a person.”

Deer said that understanding is important to the process.

“These were people,” she said. “It’s no longer just the history books that we’re looking at. We’re looking at actual people, and their modern descendants.

“The big thing in Southwest America is they want to rebury their family members and return them to where they should be,” Deer said.

And McClelland said that understanding has benefits for the scientific community, as well.

“To understand that the treatment of someone’s ancestor is an incredibly emotional and spiritual concept to many people is tremendously beneficial for ourselves to broaden our viewpoints,” he said.