The word “midget” has always been a way to bring attention to little people and intrigue audiences. In the mid-18th century, opportunities for little people were limited, resulting in many joining traveling shows that showcased an array of disabilities. Labeled as “Freak Shows,” little people were paid to display themselves to curious onlookers. In Robert Bogdan’s book “Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit,” he labeled these events as “pornography of disability.”

To stir up curiosity for these showcases, the organizers would associate the performers with animalistic qualities. A performer with excessive body hair became a wolf boy or monkey girl. One performer with dwarfism, Samuel Parks, was noted as “Hopp, The Fearless Frog Boy.” But unilaterally, almost every little person was labeled as a midget. The term comes from “midge,” which is a small fly.

Fans that came out to see the show in Phoenix shared multiple perspectives of why they went to see the show. One member of the crowd, Richard Rios, 53, of Mesa, said, “It looked like it could be funny. And why not since there is so much depressing stuff going on in the world.”

Another, who called himself just Fernando, came with his kids for “comedy” and “some violence.”

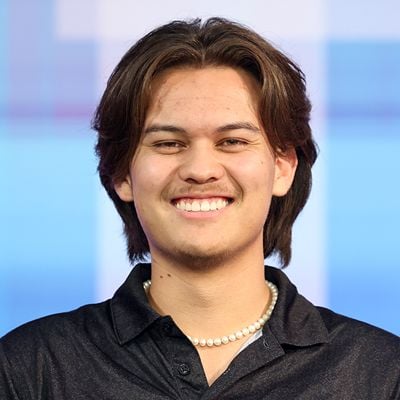

Wrestlers on the tour have different opinions of the word “midget.” Bridget the Midget uses it as her brand and embraces it, while Payne chooses to leverage it for attracting attention to the show but prefers for people to respect her and call her by her name outside of the show.