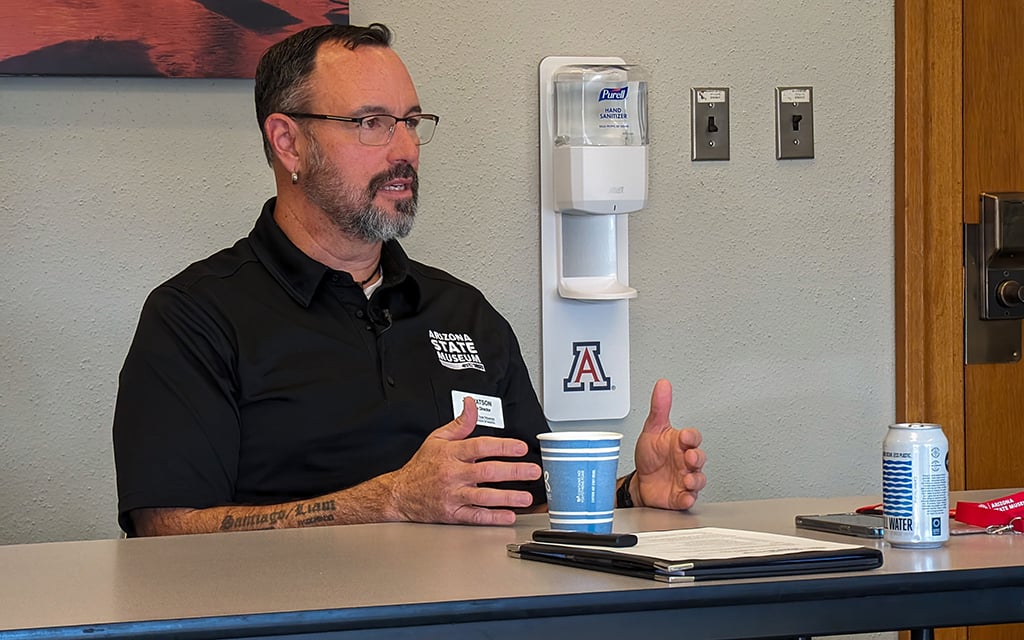

Staff mostly rely on private donations and federal grants to do repatriation work, but those dollars don’t begin to cover the costs, Watson said.

ASM has received over half a million dollars in NAGPRA grants from the federal government since 1999. Three of those grants have come in amounts of just $15,000, which Watson says isn’t enough to fund even one staff position for a quarter of a year.

“So, to do what we do with the federal collections with a NAGPRA grant, it’s impossible,” Watson said.

Work on the federal agencies’ collections takes time away from work on the museum’s own collections, contributing to its noncompliant status, Lucas said.

“We try to do two big repatriations per year, one for a federal agency and one for ASM,” Lucas said. “If we were only working on ASM’s collections, that would go a lot faster, but we are helping with a lot of collections for other institutions and so it is also our responsibility to work with them to get those collections returned.”

For this story, the museum made its staff who work on repatriation and NAGPRA compliance available for interviews and gave reporters a tour of the museum that included step-by-step explanations of the repatriation process.

According to Watson, staff also assembled thousands of pages of budget and financial records for a Feb. 5 public records request from Cronkite News and the Howard Center and turned them over to the university’s public records office for review.

That office did not provide the documents by publication deadline.

Aging facilities and unmet space needs

Under state law, ASM is the state’s archaeological repository and the destination for artifacts discovered on state land. Each year, its collections grow by about 1,000 cubic feet, or roughly the size of a small bedroom.

In a letter sent to stakeholders on April 8, ASM said it was officially out of repository space, meaning it could longer accept items of historical significance to the state.

ASM officials saw the space crunch coming.

Over a decade ago,staff at the museum began asking the university for an offsite storage facility, Watson said, and have even fundraised over $1 million to facilitate the purchase of a building.

According to budget documents from the Arizona Board of Regents, a new artifact storage facility is in the “early planning stages” and isn’t scheduled to be complete until sometime between 2026 and 2028.

ASM staff have also been waiting for a major renovation to the museum’s main building, which was originally constructed in 1927 to serve as the university’s library.

Those renovations, projected to cost $30 million, have been listed on the university’s capital improvement plan since at least 2015. It wasn’t until 2022 that the university performed a design review of the building to begin formal planning, according to records.

The renovations will address “long overdue upgrades” to the building’s structure, architecture and internal systems, according to budget documents.

Both the lack of space and the overdue renovations impact the staff’s ability to facilitate repatriations under NAGPRA, Watson said. An additional storage building and renovations would allow the museum more space to prepare human remains and funerary objects for repatriation to tribes.

“If we were able to move all those collections to off-site storage, we would have unlimited space to facilitate repatriation,” Watson said. “All of that space that is currently filled with boxes, we could fill with rehousing individuals.”

“There’s been at least three occasions where they sort of started the planning process and then it’s fallen through,” Watson said. “So, it’s really been frustrating for us.”