In June 2020, one of the four buildings housing Native American collections, known as the Alameda curation facility, flooded with shallow wastewater. “Water entered the main collections room and flooded the library, although no collections were directly damaged,” ASU reported to the park service in December 2020. The university did not elaborate on the severity of the damage in subsequent reports.

In follow-up questions, ASU declined to comment on the flood or the current state of its collections beyond what it said in its March statement to Cronkite News and the Howard Center.

“Our number one priority at the repository is living up to our NAGPRA responsibilities,” Christopher Caseldine, curator of collections for the Center for Archaeology and Society Repository, wrote in the statement. “We are the caretakers of Native American ancestors and their belongings until they go home.”

A failed search for help

In 2019, ASU told the park service that it had “an insufficient amount of staff for the substantial amount of NAGPRA work it needed to do in the years ahead,” and required money to hire a dedicated NAGPRA specialist. At the time, ASU’s archaeological repository had only one staff member.

The park service awarded ASU nearly $90,000 – more than half of which was to be used to hire a NAGPRA collections specialist.

The effort quickly became mired in delays when, according to the first progress report ASU submitted to the park service, various hiring officials were unaware of NAGPRA or what it required.

The university’s contracting office first rejected the candidate ASU selected because the office was unfamiliar with NAGPRA and did not see the need for the repository to hire a contractor, the report stated.

The then-curator of the repository appealed the decision to the contracting office’s supervisor, but that person was also unfamiliar with NAGPRA, according to the report.

The then-curator reached out to the departmental business team at the university – including the senior business manager, the grant specialist and a human resources representative – but they weren’t able to help and said that it might not be possible to hire a contractor to fill the role.

Frustrated with the delay, the candidate withdrew their application. After that, the pandemic impeded the search, the report noted.

Despite working remotely, the then-curator of collections and a postdoctoral scholar in the school made “substantial progress” documenting NAGPRA materials, namely by creating a “detailed and transparent system for recording human remains and estimating age at death, sex, and minimum number of individuals,” according to the December 2020 progress report.

ASU involved in NAGPRA’s beginnings

ASU’s NAGPRA record over the first 30 years of the law’s existence contrasts with the university’s deep engagement with NAGPRA’s passage. Key ASU faculty testified in favor of the law before Congress, and several were part of a historic dialogue that formulated some of the law’s guiding principles.

Beginning in December 1988, the Heard Museum in Phoenix hosted a year-long dialogue between Native Americans and museum representatives to resolve serious differences over how human remains should be repatriated.

The dialogue included two professors from ASU’s anthropology department and two professors from ASU’s law school. In February 1990, the panel sent a report to Congress that said respect for Native human rights should be the paramount principle when a tribe says it has a cultural affiliation with human remains or objects in a museum’s collection.

“Our hope is that this will result in solutions that will meet outstanding Native American concerns while allowing scientific investigation in appropriate situations,” the authors of the report wrote at the time. “Our further hope is that the adoption of these recommendations will lead to a new era of cooperation rather than conflict between Indian nations and museums with consequent benefits to both and to the general public.”

The panel’s moderator, the then-dean of ASU’s law school and a Heard Museum trustee, went on to endorse NAGPRA’s passage before the Senate committee considering the legislation in 1990.

That year and in the years prior, however, some members of the archaeological community were raising concerns about what a law like NAGPRA would mean for scientific research.

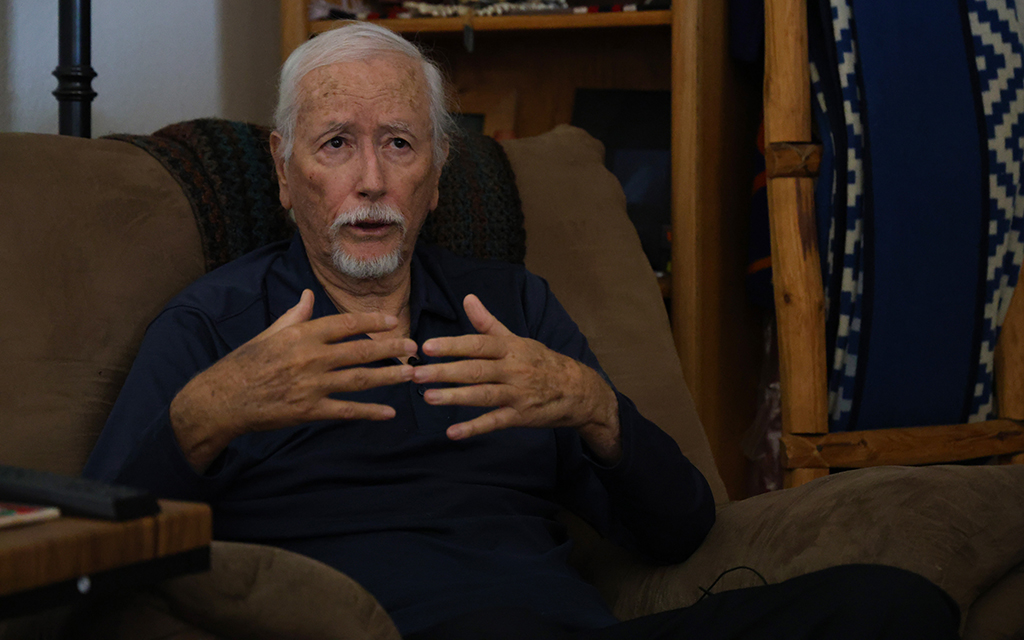

Others, such as former ASU archaeologist Keith Kintigh, were advocates for the statute.

Kintigh testified at Senate and House hearings on the drafting of NAGPRA the year it was adopted. At the time, he chaired a repatriation committee at the Society for American Archaeology, and appeared in that capacity when he testified in favor of NAGPRA before the congressional committees.

“Anthropologists are painfully aware that repatriation results in the destruction of information about the past,” Kintigh said during the House hearing. “However, we recognize that where a modern group has a reasonably clear affiliation, that group’s desire to control its own heritage takes precedence over scientific and public interests.”

Kintigh’s sway with the archaeological community played a critical role in NAGPRA’s passage, according to McKeown, a member of the NAGPRA review committee who wrote a book about the four years leading up to the repatriation law and worked on implementing it for decades.

For all its promise, NAGPRA did not resolve how institutions and tribes should treat human remains that institutions believed were not clearly identified with present-day tribes.

Some tribes came to believe that institutions were failing to recognize obvious descendants of tribes that were relocated or displaced, allowing institutions to sidestep NAGPRA requirements and avoid consultations with tribes.

The issue simmered in the first years of NAGPRA and splintered the coalition between Native Americans and institutions that led to NAGPRA’s passage.

In the early 2000s, ASU’s law school led a dialogue between tribes and institutions to mediate the issue.

The park service made two attempts to adopt new regulations about so-called culturally unidentifiable human remains in the mid-to-late 2000s. But it faced fierce opposition from the museum and archaeological communities, including the Society for American Archaeology.

In 2008, ASU’s Kintigh called the proposed rules on culturally unidentifiable remains a serious threat and urged the society to fight them “in every way we can,” he wrote in SAA’s magazine. Kintigh served as president of the society from 1999 to 2001.

“SAA has consistently used a moderate tone in its repatriation positions,” Kintigh wrote. “Strategic considerations and our responsibilities to the archaeological record demand that we now play ‘hard ball.’”

The park service finally adopted a new rule on culturally unidentifiable remains in 2010. That same year, ASU hosted a national conference on the 20th anniversary of NAGPRA’s passage, attracting a who’s who of Native American scholars, legal professionals and advocates.

The park service ultimately did away entirely with the designation of culturally unidentifiable remains in a revision of NAGPRA that went into effect in January.

Cronkite News and the Howard Center interviewed Kintigh and another former ASU archaeologist to learn more about the university’s NAGPRA record after 1990.

Kintigh confirmed he was the chair of the Society for American Archaeology’s task force on repatriation when NAGPRA was passed and was intensely involved in drafting the legislation, advocating for the interests of the scientific community and working to find a balance between traditional interests – those of lineal descendants and contemporary tribes – and “what we believed, and I still believe, are valid scientific and public interests.”

Kintigh worked at ASU for more than three decades, beginning in 1987. Despite his involvement in the drafting and passage of NAGPRA, he said he did not work on repatriation for the university or inquire about ASU’s compliance in regards to its own collections.

“We were mainly coordinating with the federal agencies,” Kintigh said. “I think my understanding when I retired was that we had done what we were supposed to do.”

Cronkite News and the Howard Center also interviewed Frank McManamon, another retired ASU archaeologist with extensive NAGPRA credentials.

McManamon led the Center for Digital Antiquity at ASU, a research center aimed at preserving digital records of archaeological resources, from 2009 to 2019. Before coming to ASU, he served as the chief archaeologist of the park service for almost 15 years. In this role, he directly oversaw the implementation of NAGPRA from 1990 to 1999. For a brief period from late 2018 to 2019, he worked at ASU while serving as a member of the NAGPRA Review Committee.

McManamon said his many years working on NAGPRA for the park service were difficult and included uncomfortable moments where his objectivity was questioned by people from other organizations. He was reluctant to engage with repatriation work at ASU, he said.

“I didn’t actually go looking for new NAGPRA frontiers to explore or get myself involved in,” McManamon said. “I knew how complicated it could be.”

Cronkite News and the Howard Center unsuccessfully attempted to locate the former curator of the repository who wrote the 2019 NAGPRA grant application and 2020 progress report. Reporters also reached out to another archaeologist who worked as the curator of the repository in the mid-2010s who declined to comment.