Best foot forward: Tucson farrier educates Native American communities on horseshoeing

Best foot forward: Tucson farrier educates Native American communities on horseshoeing

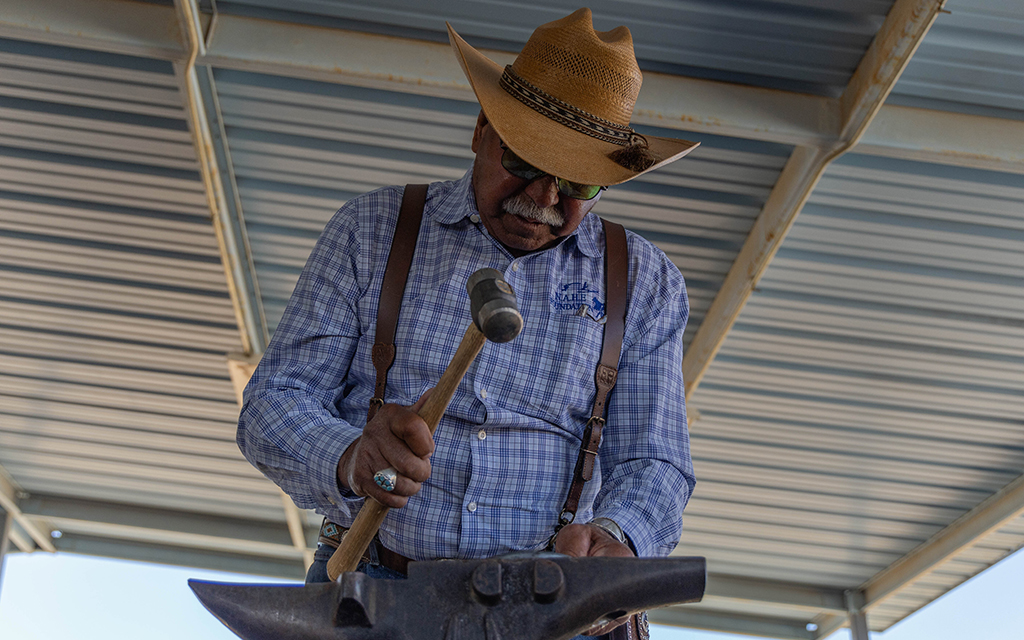

George Goode explains the significance of farrier education through his nonprofit organization, the Native American Horse Education Foundation, which provides courses to Native American communities in Sells.

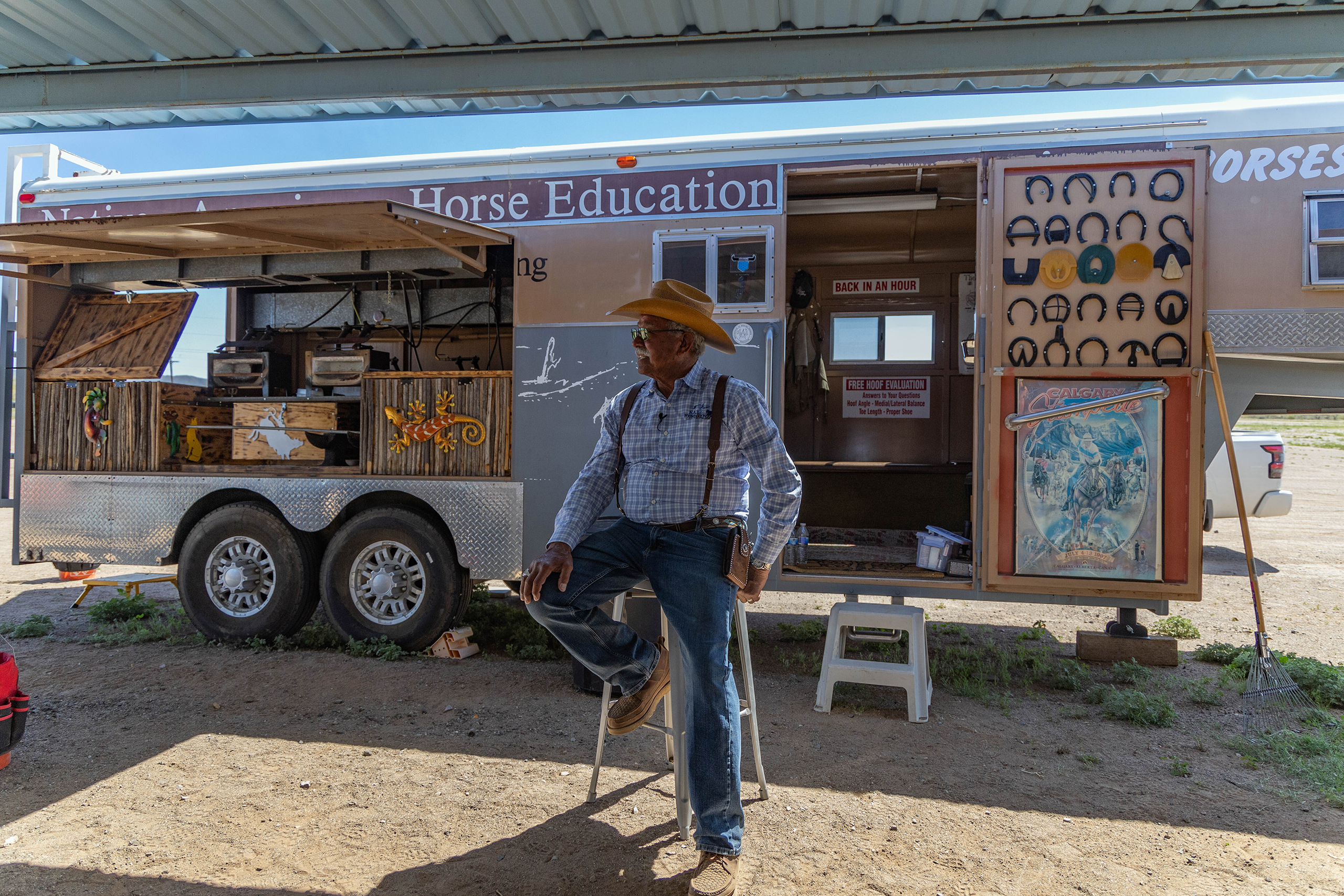

George Goode sits in front of his trailer on the Tohono O’odham Nation on April 10, 2024. Goode bought his trailer 30 years ago when the Native American Horse Education Foundation was still a dream. Now, he uses the trailer daily to help teach equine education to Native Americans. It houses materials necessary for horseshoeing, including burners, anvils, nails and shoes. (Photo by Sam Ballesteros/Cronkite News)