“I was just trying to exit the court as quickly as possible,” Clark told reporters after the game, “so I started running and I was absolutely just hammered by somebody trying to run onto the court.”

Although Clark did not sustain any injuries, a more recent incident on the men’s side did not bear the same results.

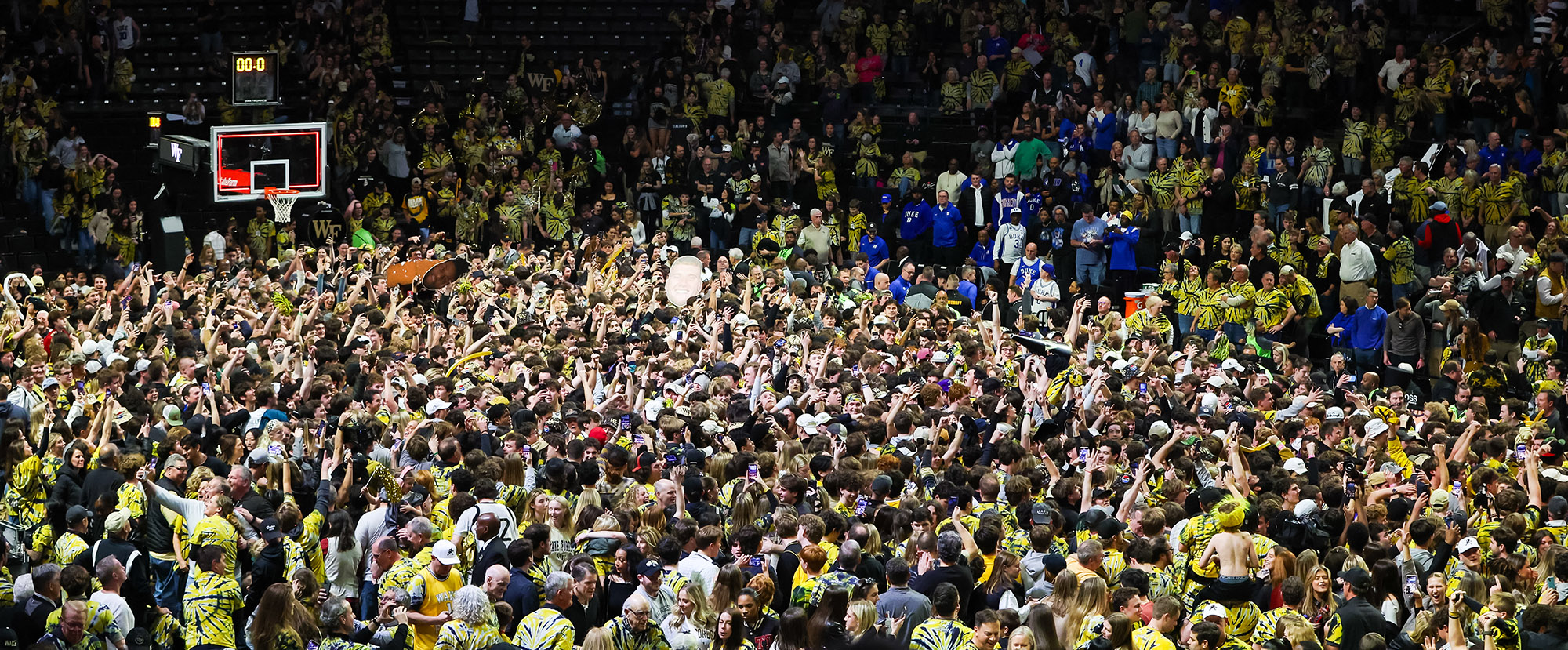

After Wake Forest defeated then eighth-ranked Duke, 83-79, on the Demon Deacons’ home court, the court was quickly engulfed by a wave of excited fans. In the blink of an eye, 7-foot sophomore Duke center Kyle Filipowski found himself in a dangerous situation.

After a fan collided with Filipowski, he was forced to hobble off of the court while being helped to the locker room.

“I feel like it was personal, intentional for sure. There’s no excuse for that,” Filiposwki said.

Blue Devils coach Jon Scheyer said that his center sprained his ankle and asked in the post game press conference, “When are we going to ban court-storming?”

The gravity of the incident prompted ACC Commissioner Jim Phillips to release a statement.

“The safety of our student-athletes is always our top priority. We have been and will continue to be in contact with both Duke and Wake Forest regarding what happened,” Phillips said.

Is more regulation needed?

Despite the argument that administrators have more of a connection with their students, Sommers believes that if there was ever a time where entities like the AIA wanted to completely eliminate court-storming, there would have to be more-uniform policies set in place at higher levels to create uniformity. For Sommers, the school-by-school nature of the regulation would foster a confusing environment within the already very difficult task of altering tradition.

“You take the parallel to parents that, if one parent lets you do this the other one doesn’t, or you go to your friend’s house and the rules are different,” Sommers said.

Non-educated fans are one of the biggest dangers to safety in Hines’ mind, and while schools that possess shinier trophy cabinets usually have a more rule-savvy fan base, others need extra guidance in preparation for the big moments.

“If you have a school that comes for the first time, and they’re really excited, and all of a sudden you win one. Maybe you win one on a last-second shot or a catch in the end zone at the last minute, they get excited,” Hines said. “And what do they see in college games?”

One particular Arizona high school boy’s basketball court-storming incident still haunts the minds of many even 20 years after its occurrence.

On Friday, Feb. 6, 2004, Tucson High won 62-54 at home against Salpointe Catholic, which had captured the Class 5A boys basketball championship the year before. The school’s athletic director at the time, Herman House, estimated that there were about 1,000 fans in attendance and about 200 participated in rushing the court once the clock hit zero, the Associated Press reported.

After drawing a lot of attention by scoring a key dunk with just a few minutes left to play, senior Joe Kay was right in the middle of the chaos. Tucson High coach Gary Lewis said a torn carotid artery and a cracked portion of Kay’s jaw triggered a stroke that left him without movement in his right arm and right leg.

Kay was not only a starter on the basketball team, but also a key player for the school’s volleyball squad as well, earning a volleyball scholarship to Stanford, while also maintaining a 4.0 grade point average, according to House and Lewis. Yet, his life was permanently altered in an instant.

“Twenty years have passed and I’m still disabled,’’ Kay told the Arizona Daily Star recently. “Every time I see people rush the court, it’s ridiculous. It’s bull. The college kids act like this is a rite of passage for them. It’s BS. Are they going to wait until someone gets hurt the way I did? My body will be constantly affected until I die.’’

Two decades later, schools are still trying to find the right formula for an environment that is safe for all parties involved.

Indoor gyms pose greater crowd control issues, and in the second half of February, local Valley high schools prepared their student sections for the basketball postseason. At Sunnyslope High School, fans packed the gymnasium to maximum capacity to watch the Vikings host Millennium on Feb. 23 for the AZPreps365 game of the week.

The noise was impressive, and even first-quarter highlight plays sounded like game-deciding moments. To put it simply, there was not much elbow room, especially in the student sections.

Unfortunately, not all fans had the opportunity to watch as administrators turned away disappointed high schoolers at the door.

“It’s usually a packed gym, but it’s never this bad,” Sunnyslope senior Gavin Eagar said after he was unable to buy a ticket at the entrance alongside two of his classmates.

Sunnyslope principal Jonathan Parker was standing outside of the school’s entrance to the gym and breaking the bad news to fans who had delayed buying their ticket at the last minute.

After setting the limit on the number of tickets available at 1,100 on a popular high school ticketing app called GoFan, Parker mentioned that the ability to purchase tickets at the door was halted about 30 minutes prior to tipoff.