Estrada said he and his “compa,” the late Bob Bohrn, who was affectionately known as “Coach Bob,” were responsible for jump-starting the Pop Warner program in Winkelman, where many of the kids in the area got their first feel of the gridiron. They also collaborated on the school’s junior high program before reaching Hayden High School.

“Unfortunately, he passed away last year of cancer,” Estrada said. “But we were together for years. And I used to tell him, because he was my compa – he baptized my eldest son – I would say to him, ‘Compa, I remember when you guys used to walk down to the field, and I’d stand here, you know, and hear the cleats and that would get me motivated.’”

When the Lobos stormed the field for the 1A championship game at Coronado High School in Scottsdale, they were motivated by Coach Bob as all players wrote his name on their wrist tapes.

The Lobos take pride in the many scars that are a reminder of what the school and community have gone through.

Hayden’s basketball gym has a mural that reads, “NEVER GIVE UP! STAY MONTI STRONG,” along with a photo to honor former student Santiago “King Monti” Piña, a three-sport athlete at Hayden who survived significant head trauma suffered in a car accident in 2015. Piña’s chances at life once looked bleak as the accident landed him in a coma and on life support for three weeks.

And in 2017, after the Las Vegas music festival shooting, doctors told the family of former Hayden High School student Jovanna Calzadillas, who was wounded in the shooting, that she would not survive the bullet that pierced three lobes in her brain. Remarkably, she did.

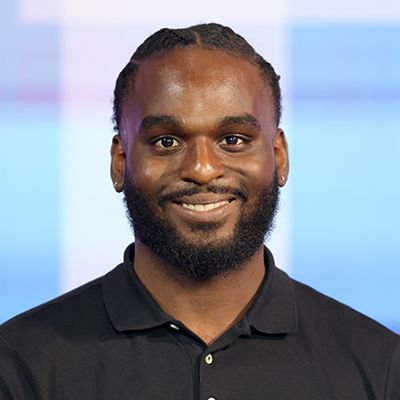

Since recovering from that life-threatening injury, Calzadillas and her husband, Frank Calzadillas, have sponsored a $500 scholarship for Hayden High School students called the Perseverance Scholarship.

“It’s unfortunate what happened, but, you know, they play a positive role,” said Lagunas, who lost a 19-year-old son in a truck rollover crash. “They’ve shown that kids can overcome some of those difficulties.”

Senior running back and linebacker Renee Ochoa said those former students play a “big role” in what the teams now want to accomplish on the field and help explain the passion they share while doing it.

“Just to have that to fill you up and go out there and use it as motivation,” Ochoa said. “Just to know they came from Hayden, we have to go out there and show them we have a lot of heart and soul.”