PHOENIX – Zion Gastelum was 2 years old when he died days after receiving root canals on his baby teeth during a visit to a dentist in Yuma in 2017.

Lizeth Lares was just 4 when she died after getting a tooth pulled a year prior at the same dental office.

And two more people died after visiting the dentist this year, meeting minutes of the Arizona State Board of Dental Examiners show.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story misspelled the last name of Ryan Edmonson, the executive director of Arizona State Board of Dental Examiners. It also misstated the year he took his position. The story here has been corrected, and it also contains clarifications to indicate Edmonson believes the board has improved since he began his role and says there are no vacancies on the board. Clients who used earlier versions are asked to run the correction found here.

Yet, Arizonans would have a hard time learning about these cases from the state dental board, the 110-year old agency that regulates the dental industry, licenses dental professionals and investigates complaints against them.

Details about problem dentists are hidden under layers of bureaucracy, a tangled complaint system and a public-facing website that is virtually unnavigable, an investigation by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism found.

And in rare instances when patients die or are seriously injured during a procedure, the board does little to hold dentists accountable, the investigation found.

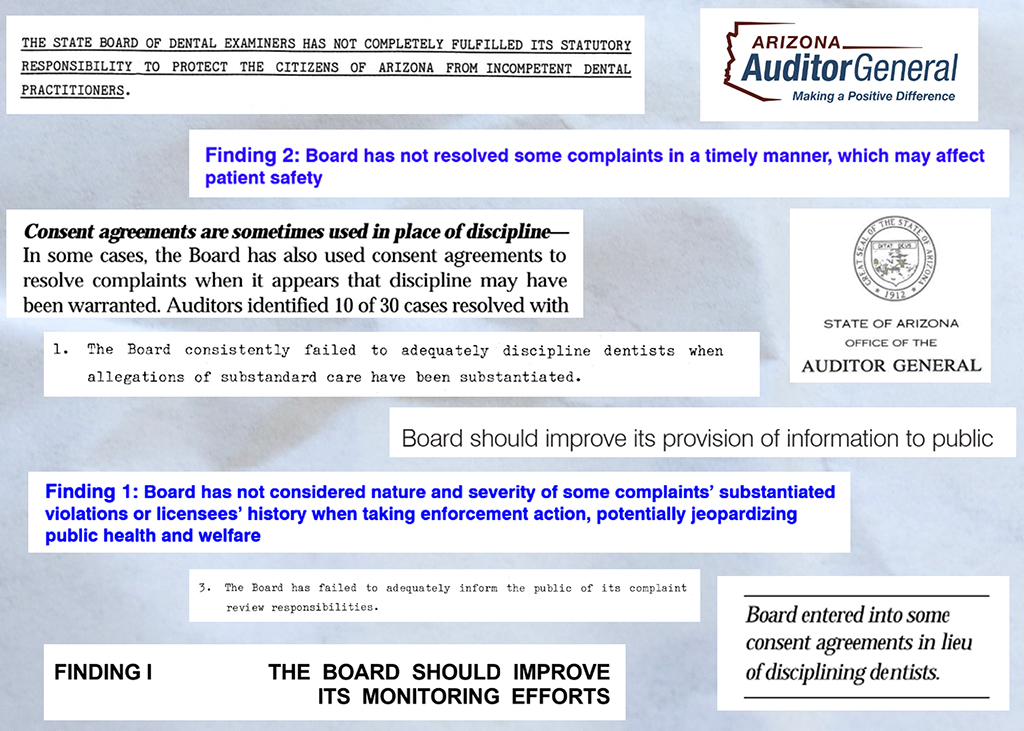

State audits chronicle similar failures stretching back nearly half a century.

Ryan Edmonson, the board’s executive director, told the Howard Center in an interview that the board was the worst-run he’d ever been a part of when he joined in 2019, but that it had made significant strides in performance since then.

In recent years, the board has undergone several big shake-ups. In 2018, the board’s executive director retired after an investigation by ABC15 uncovered she ignored warnings about a dentist who falsified anesthesia credentials.

State laws that protect dentists and limit public disclosure of misconduct govern some of the board’s actions. But the board has leeway to develop best practices.

The state board is made up of 11 people appointed by the governor: six dentists, two dental hygienists, two members of the public and one business member. They are each allowed to serve two consecutive four-year terms.

The board’s preponderance of dental professionals leads to decisions that are intended to help dentists learn from their mistakes, but can outrage patients’ families.

“You can’t have a much worse consequence than a dead baby,” said Mike Poli, who settled a malpractice lawsuit against the dentists and dental office on behalf of Zion’s family. “If that doesn’t motivate (the board) to get busy with regulatory oversight, then I don’t know what would.”

In 2017, Zion was placed under anesthesia for his root canals. He never regained consciousness. The oxygen tanks meant to supplement his breathing were empty or not working properly, the dental board found, according to its records. At the hospital, he was diagnosed as brain dead and he died four days later.

The board’s leniency

The board faulted Dr. Aaron Roberts, Zion’s anesthesiologist, for failing to follow proper procedures, and gave him three years of probation that still let him practice under the supervision of another licensed anesthesiologist. Roberts did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Zion’s dentist, Stephen Montoya, signed a non-disciplinary consent agreement with the board. The board found his mistakes were less serious and didn’t fall outside the standard of care. The board required him to take 10 hours of continuing education.

“It just wasn’t an ideal situation. So now that it’s been so long, I look back on it and I mostly feel that the board handled it fairly,” Montoya told a Howard Center reporter.

Veronica Gastelum, Zion’s mother, said she was expecting harsher consequences.

“This was a child,” she said.

Board-ordered continuing education courses are offered through groups such as the Arizona Dental Association or at a dental school. Some involve an in-person seminar; others are online webinars. All courses must be approved by the board to ensure their syllabi meet the consent agreement requirements. According to the board’s policy, it’s meant to help dental professionals understand the current best practices for procedures and treatments.

But requiring continuing education is the board’s default punishment, said Craigg Voightmann, a dental malpractice attorney who has handled hundreds of lawsuits over 15 years of practice.

“Dentists have this perception that the board’s going to come out and hammer them, and I think it rarely happens,” said Voightmann. “Really, what’s happening is they’re just getting a public reprimand by a letter in their file and continuing education.”