The Phoenix Ramblers pose after winning their first of three national championships in 1940. (Photo courtesy of Lynn Ames)

PHOENIX – When the PBSW Phoenix Ramblers and A-1 Queens faced off, it was the hottest ticket in town, selling out crowds of 10,000 night after night.

At the time, the rivalry was as fierce as that of Arizona State University and the University of Arizona. Though the Ramblers never wore the same uniform season after season or even the same colors, one thing was certain.

There would always be an abundance of energy, passion and rowdiness from the crowd and players alike who simply loved the game of softball. When the two rival teams met, fans would sit on opposite sides of the stands at Rambler Field in downtown Phoenix off Washington Street, and never dare to cross.

Fights and arguments were a common occurrence, just a part of the game. Dot Wilkinson, the Ramblers’ hard-nosed catcher from South Phoenix who died March 18 at 101 years old, often found herself in the thick of skirmishes.

“Dot had a neighbor and there was another person sitting right near her who was rooting for the Queens and one of them said something wrong,” said Lynn Ames, a best-selling author and Wilkinson’s longtime friend. “They both started smacking each other with their pocketbooks. They had to be separated.”

That’s how it was in the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s when fastpitch softball ruled the Phoenix sports scene.

The Phoenix Ramblers pose after winning their first of three national championships in 1940. (Photo courtesy of Lynn Ames)

The Ramblers were an amateur team that roamed all over the country each summer, competing in games and tournaments. Wilkinson was a phenom, beloved in Arizona for her strong character and wowing skills, while trailblazing pitcher Billie Harris drew comparisons to Jackie Robinson.

In the 1940s, the Ramblers are believed to be the first team to ever bring Arizona a national championship, and Wilkinson has said it was the highlight of her life.

“That was the first one they won,” Ames said. “It was the pinnacle of her career. There was nothing that ever eclipsed that for her.”

The Ramblers went on to win two more championships, picking up back-to-back titles in 1948 and ‘49. On both of those teams, Wilkinson, who hit over .300 in her career and was a prolific home run hitter, was the only player who stayed with the team through its 33-year existence.

Wilkinson has been compared to Yankees legend Yogi Berra for her tenacity and knowledge of the game. Ames described her as fierce, indestructible and tenacious.

Wilkinson had the ability to throw out runners without rising from her catcher’s stance and was known for being hard-nosed and arguing with umpires.

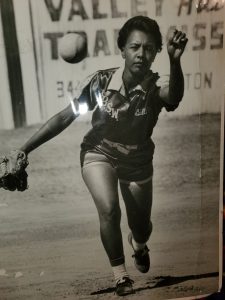

Billie Harris became the first African American player to play in the amateur league. She learned about the Phoenix Ramblers from a magazine article. (Photo courtesy of Bridget Branch)

“There was a guy who was sitting behind home plate, and he kept heckling her,” Ames said. “She finally turned around and said, ‘If you bother me one more time, I swear to God, you better hurry up when the game’s over.’ He didn’t believe her and when the game ended, she went tearing after him. She whacked him over the head with a catcher’s mitt and then walked out.”

That’s who Wilkinson was from a young age. She grew up in a poor family in Phoenix and always loved playing sports. She wasn’t much for school and academics, but had a natural raw talent when it came to athletics.

At 10, after being seen by Ford Hoffman, the team’s manager, in a schoolyard competition, Wilkinson was asked if she wanted to be a bat girl for the Ramblers. Shortly thereafter she became the team’s starting catcher using her strength and arm to aid her behind the dish.

Harris, her younger teammate, was a much calmer, sweet personality. However, as the first Black player to play in the amateur league, she had to build a lot of character and strength.

Harris became a Rambler after reading about the team in an Arizona Highways article. She was playing on a different team at the time and went to Tempe to compete in a tournament, where someone from the Ramblers asked her if she wanted to come to Phoenix from Tucson and try out.

“So, I did,” Harris, 90, said. “That’s how I got started.”

In her long career, which lasted until she was 74 years old, Harris threw 70 no-hitters, pitched four perfect games, scored 123 runs and suited up for 264 games. This helped lead the Ramblers and other teams she played for to on-the-field success.

However, it was not all sunshine and rainbows for Harris, Wilkinson and their teammates.

Being a softball player in the mid-1900s came with many challenges, including hiding identities and earning a living.

One of the biggest challenges, Harris said, was holding and keeping a job. They made very little money playing for the Ramblers and often held various jobs while off the diamond.

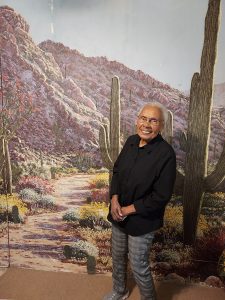

Dot Wilkinson, left, and best-selling author Lynn Ames, who wrote a biography about Wilkinson, enjoy each other’s company as longtime friends. (Photo courtesy of Lynn Ames)

Harris worked for a clothing store, but found it nearly impossible to keep the job with the demands of the Ramblers’ schedule.

“I had to quit my job each time we had road trips,” Harris said. “I would go back on the next Monday and find out if there was anything that I could do, so that I would still have money coming in.”

She said the process went on for roughly four years, before the store realized they could no longer employ her with the team’s busy travel schedule. Ames said each time a player quit their jobs, they would lose any status they had gained and would have to start from the bottom and re-earn all their promotions.

Wilkinson had a handful of jobs, but her most prevalent one was in real estate. Hoffman opened his own business and brought Wilkinson on board, which eventually led to her own successful company, where she would buy, renovate and sell homes.

Real estate led to a small fortune for Wilkinson, allowing her financial stability.

For Harris, another challenge that presented itself was being Black. For the most part teammates were friendly, Harris said, but sometimes they struggled to understand what she was going through. Fans and umpires were less understanding and often heckled her for her race.

“I had negative words spoken out of the stands and was called a few names,” Harris said.

It was worse than Harris led on, said Bridget Branch, who helped Harris during her interview with Cronkite Sports.

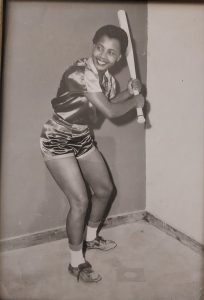

Billie Harris, who played softball until she was 74 years old, threw 70 no-hitters and four perfect games in 264 games. (Photo courtesy of Bridget Branch)

For roughly two seasons, Harris lived in a chicken coop near Rambler Field because of her race. When the team was on the road, Harris was not able to stay in hotels with the rest of the white players and instead was forced to room with Black families.

Because she broke the color barrier in softball and had lots of on-field success, the news media often compared Harris to Jackie Robinson, who broke the MLB color barrier in 1947 when he played for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

“At the same time Jackie Robinson was breaking into baseball is about the same time I was trying to break into softball,” Harris said. “Somebody tagged me with that title and it’s because we were both breaking it at about the same time.”

For Wilkinson, an additional challenge that presented itself was her sexuality. Wilkinson was a lesbian who fell in love with fellow softball player Estelle “Ricki” Caito, but never publicly made their relationship known until Caito’s death in 2011.

“You didn’t acknowledge it,” Ames said. “You didn’t announce it. That’s just how it was at the time. When Ricki passed away, Dot said to me ‘I’ll be damned if I’m gonna bury that woman and not have people know what she meant to me.”

Their love wasn’t always so strong though, as it began as a rivalry. Caito played for another fierce rival of the Ramblers, the Orange Lioness, and the two teams absolutely hated each other, Ames said.

“They were truly such competitors on the field,” Ames said. “They fought all the time. They were like oil and water. There was one point where Ricki literally jumped on Dot’s back and Dot carried her all the way to third base and just knocked her off, but they always had tremendous respect for each other.”

That respect eventually turned into a friendship and later a relationship. They spent 48 years together as a couple, albeit one that was mostly shielded from outsiders.

Despite all their struggles and hardships, years later Harris and Wilkinson were honored for their impact on the sport and success on the field.

In 1979, Harris was inducted into the Arizona Sports Hall of Fame and in 1982, surrounded by family, she became the first African American woman inducted into the Amateur Softball Association Hall of Fame.

“It’s nice to be inducted in the Hall of Fames,” Harris said. “I’m very proud of that, but I just wanted to play softball.”

Wilkinson too was inducted into various halls of fame. In 1970 she was inducted into the National Softball Hall of Fame and Museum and in 1976, she was the first woman inducted into the Arizona Sports Hall of Fame.

“At the time there were no women allowed to be members of the press box,” Ames explained. “She had been honored by them before and she’d never been allowed to sit on the floor with them. So, when it got to this one, she said ‘Unless you will allow my mother and friends to come, I’m not going to accept it.’”

After some hesitation, the male-run Hall of Fame finally agreed, and the rule was lifted to allow women into the Arizona Sports Hall of Fame.

Billie Harris was forced to quit her job each time the Phoenix Ramblers played on the road. On the field, she faced even more challenges. (Photo courtesy of Bridget Branch)

Wilkinson broke that glass ceiling with typical panache. When she was inducted, many people booed, but she said thanks and told the gentleman booing her she felt at home. They gave her a standing ovation shortly after.

Even with all their accolades, all Harris and Wilkinson wanted to do was play ball. That was their love.

Five years ago, to celebrate her 85th birthday, that’s exactly what Harris did, play softball. Wilkinson’s affair with the sport was equally strong. Ames said up until Wilkinson’s death, she enjoyed watching ASU softball and would even coach the games through the television.

“If it wasn’t for them, we wouldn’t be here,” Nikki Balich, the Executive Director of the Arizona Sports and Entertainment Commission, said of the pioneering softball players. “They’ve made an impact on sports, women’s sports and Arizona sports like, I don’t know any other women who has.”

Eventually though all good things had to come to an end. In the mid-1960s the Ramblers were no longer and slowly the team faded from memory.

“For her (Dot), there were a lot of other things going on and the girls and women who were playing were interested in other things.” Ames said. “They didn’t seem to be as committed to softball as the players in Dot’s era had been. They didn’t seem to have that burning desire to win the way they had before.”

The game was no longer as fun, it wasn’t the same as it was when tens of thousands of rowdy fans would pack into the downtown ballpark, and the Ramblers and competitive fastpitch softball in Arizona eventually gave way to other pastimes.

Harris and Wilkinson never forgot about each other though. Until her death earlier this month, Wilkinson and Harris talked every morning.

“To her (Wilkinson) relationships were everything,” Ames said. “She stayed close to every single player that ever wore a Rambler uniform and continued to be great friends with them. Those relationships formed the backbone of Dot’s life.”

Harris remains the last one alive from those Rambler teams to tell their story. It’s a story of Arizona at a specific time, a story of fearless women who just wanted to play ball, a story of failures and triumph.

“The Rambler experience here in Phoenix is so unique and so tied to the history of women and is the embodiment of an area,” Ames said. “It was an integral part of the community at the time and really defined the growing up of Phoenix.”

“The Ramblers were a phenomenon,” Ames said. “A once-in-a-lifetime phenomenon.”