PHOENIX – On a blistering Saturday afternoon at Oakland Coliseum, Harvey Shank, a lanky 23-year-old right-hander, stepped on the mound for the California Angels for the first time.

It was May 16, 1970, two days before the U.S. release of The Beatles’ final album “Let it Be,” and less than one year after Neil Armstrong stepped on the moon.

Shank made his MLB debut just 30 miles from where he was raised in Redwood City, California. His parents had since moved out of the state, but his Little League coach was in attendance, along with 5,653 others who got to see the pitcher’s first – and only – Major League Baseball appearance.

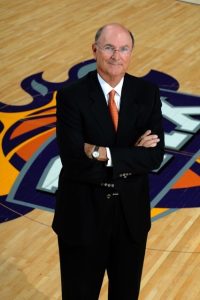

Shank went on to pitch sponsorships for the Phoenix Suns for 42 years before retiring in 2013 as a senior executive vice president, but he still remembers his day on the mound.

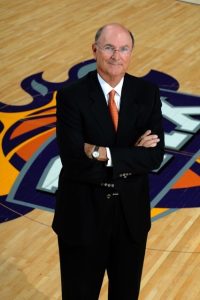

Harvey Shank stands at the center of the Phoenix Suns’ home court in the arena he helped secure the naming rights for as a Suns executive. Now called the Footprint Center, it was once the Talking Stick Resort Arena, U.S. Airways Center and America West Arena. (Photo courtesy of Harvey Shank)

In the bottom of the fifth inning, the Angels called Shank from the bullpen with the team trailing Oakland 7-3. The “Swingin A’s” boasted four future Hall of Famers and were two years away from winning three consecutive World Series trophies.

But that fifth inning went smoothly for Shank, a 6-foot-4, 220-pounder.

The A’s had scored in each of the first four innings, but Shank shut them down in the fifth.

He walked Don Mincher, then settled down to retire three consecutive batters.

The sixth inning wasn’t as easy.

A pair of singles by Felipe Alou and Bert Campaneris put two runners on base with just one out. In the thick of the batting order, the great Reggie Jackson came to the plate.

Shank’s first two pitches were sliders and Jackson swung and missed at both. Shank breathed a sigh of relief.

“His swing was so powerful,” Shank said, reminiscing 52 years later. “Had he hit either one of them, it would still be circling the Earth.”

Eventually, the veteran Jackson won out with his patience and walked to first base on a 3-2 ball. The walk loaded the bases and brought All-Star third baseman Sal Bando to the batter’s box.

Angels catcher Tom Egan waved his hands, signaling for Shank to do something he had never done in a game before – attempt to pick off the second-base runner with the bases loaded. He had done it in practice, but now, with the bases loaded and another All-Star at first base, he was asked to pull it off in his MLB debut.

No pressure. Shank pivoted on the mound and let it fly – safe.

“The best part of it was that I didn’t throw it into center field,” he said, laughing.

Again, Shank went to his trusty slider. Bando’s eyes lit up, and he swung hard, but the ball popped up into foul territory for the inning’s second out. When Mincher grounded out, Shank escaped the inning unscathed.

In the seventh inning, he recorded his only career strikeout against Oakland catcher Dave Duncan. After two more outs capped off a scoreless inning, the Angels pulled Shank from the game, replacing him with two-time All-Star Dave LaRoche.

Of course, Shank had no way to know that it would be his only appearance in the big leagues, but he left the game with a career ERA of 0.00, which is where it will remain for perpetuity.

“It doesn’t get any lower than that, does it?” Shank said.

Leaving baseball behind

Before his big day in Oakland, Shank had bounced around minor league organizations, playing for three teams in three years.

He lived at home while playing for the San José Bees in 1968. With the El Paso SunKings, he missed half of the 1969 season after getting called into active duty during the Vietnam War.

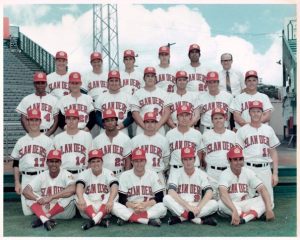

And with the Hawai’i Islanders in 1970, Shank remembers a packed Honolulu Stadium, with many of the fans carrying transistor radios and listening to the Islanders’ play-by-play call from a 25-year-old broadcaster named Al Michaels.

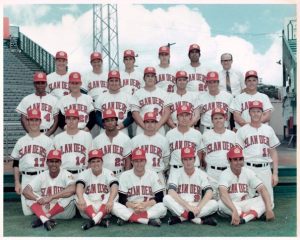

Harvey Shank (8) poses for a team photo with the Hawaii Islanders, the team he played with in 1970, before being called up for an appearance in the majors. Club manager Chuck Tanner, top left, went on to lead the Pittsburgh Pirates to a 1979 World Series victory. (Photo courtesy of Harvey Shank)

In 1971, a year after appearing in the majors, Shank was assigned to play for the Salt Lake City Angels, and he realized then that his baseball career had hit its ceiling.

“I could’ve gone back and played Triple-A,” he said. “But I just didn’t think I had enough stuff to make it as a reliever in the big leagues.”

That fall, Shank decided to forego his baseball career and take an internship in the marketing department with the fledgling Phoenix Suns organization. Even though he had been playing baseball since grade school, choosing to leave the diamond behind wasn’t difficult.

“You come to a point when you make a decision, (where) you know this is over and it’s time to move on,” Shank said.

With the Suns, he faced a new learning curve. Prior to playing baseball professionally, Shank pitched at Stanford University, so he came into his new job with a prestigious degree, but still had a lot to learn about sales.

“At Stanford, I majored in baseball and got a degree in political science,” said Shank, who still holds the second-best career ERA (1.10) in Cardinal baseball history. “When I got to the Suns, I had never really sold anything in my life.”

Through a friendship with General Manager Jerry Colangelo and Ted Podleski, the team’s promotions director, Shank learned to be a whole different kind of pitchman.

He quickly worked his way up from intern to assistant sales promotion manager, impressing Suns front office members with his ability to come up with creative sponsorship ideas.

Shank was creating clever promotions even before the invention of the high five. In fact, when the high five came to popularity in the late ‘70s, Shank saw an opportunity there, too.

He conceived a “High Five Kids” program where five children were chosen each game to stand with the Suns during the introduction of starting lineups. Bringing joy to the children of potential sponsors was an easy way to further the connection between the team and its partners.

“(You’ve) never seen anything, in terms of the smiles on parents’ faces, until you see that,” Shank said.

Over four decades in Phoenix, Shank had a hand in building some of the most iconic pieces of the Suns’ identity. He was the first person to approach Henry Rojas about being the original Suns Gorilla mascot in 1979. And after the Suns built a new arena downtown, Shank sold the naming rights to Phoenix-based America West Airlines.

America West Arena, which later became U.S. Airways Center when the airlines combined, opened in 1992.

Harvey Shank, the people person

Robert Schiller first met Shank when he was 12 years old and working as a Suns ball boy. While in college, Schiller worked as a stats runner for the Suns, and eventually secured a job with the team as a marketing manager.

He remembers that Shank’s sponsorship presentations were always impressive, but it was his curious demeanor and magnetic personality that sealed deals.

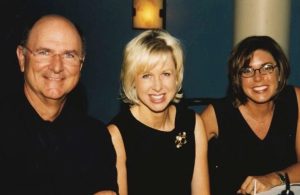

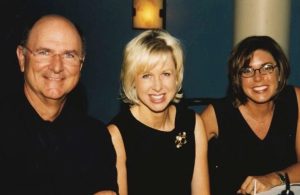

Harvey Shank, left, Cathy Kleeman and Heidi Coupland pose for a picture. Kleeman worked with Shank and the Suns for eight years as a vice president of marketing. (Photo courtesy of Harvey Shank)

“You can prepare and have the greatest deck in the world, but sometimes you just go in and you meet with a customer or partner, have a great conversation and you don’t ever need that,” Schiller said. “You get it all done (through) just relationships – that was Harvey.”

“It was all about the show,” said Tom Hecht, who worked with Shank for a decade as a Suns director of corporate marketing. “It was all about selling that sizzle, and he was very good at it.”

Bonnie Senft, who worked with Shank for five years as a sponsorship business manager, said that he created a healthy culture in the Suns office.

“(Harvey’s) door was always open,” she said. “You could always go talk to him, even if things weren’t going quite the way we all wanted to.”

Cathy Kleeman worked with the Suns for eight years as the vice president of marketing, and she remembers Shank for the connections he built with those he worked with. His relationships were purposeful – Shank’s Rolodex might have had hundreds of names in it, but he could tell someone details about the lives of each and every person in it.

“It really comes down to how you treat people,” he said. “When I was selling, I was looking at the relationship I was developing.”

Kleeman said Shank always prioritized family, too. He has one son, Jon, who also went on to play baseball at Stanford.

When Kleeman got pregnant, she hadn’t told many people that she was expecting her first child. However, when her father came to visit and tour the arena, Shank arranged a whole presentation to play on the Jumbotron to inform Kleeman’s dad that he was about to be a grandparent.

“(Harvey) would just get genuine joy out of any of our victories, or what was going on in our family life,” Kleeman said.

After his time in Phoenix, Hecht went on to work for the Milwaukee Brewers. In his first year working in baseball, Hecht visited the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown for his son’s baseball tournament.

Hecht learned that the Hall keeps a file on every player who appeared in the majors, no matter how short their career was – and sure enough, he found a file on Shank.

“The file was very thin, but it was there,” Hecht said. “I took some pictures and I sent it to Harvey and said, ‘Harvey, I don’t know if you know this, but you’re in the Hall of Fame.’”

Long enough for a cup of coffee

With that single major league appearance, Shank became the 601st “cup of coffee” pitcher in MLB history, which refers to a player who only appeared for one game in the majors – just long enough for a cup of coffee.

The list features players like Flame Delhi, the first Arizona-born player to ever make it to the majors. Delhi, who was born in the long-lost town of Harqua Hala, Arizona, made his debut with the Chicago White Sox in 1912. And Moonlight Graham, whose single 1905 major league appearance became iconic when he was depicted in the fictional 1989 film “Field of Dreams,” is maybe the most famous player on the “cup of coffee” list.

Years later, Shank still receives requests in the mail from collectors, asking him to sign a baseball card. There’s even a hand-written letter that Shank wrote to a collector in 1971 currently selling on eBay for $10.

Today, Shank returns autograph requests with a signature on an index card, wedged between the pages of a book about Christian faith. The trading card he usually gets requests to sign includes a picture of him posing in an Angels uniform.

“They didn’t even make a card of me,” Shank said, laughing. “Somebody found that picture from when I was at Stanford and superimposed the Angel uniform on me.”

Almost 10 years after retiring from his job with the Suns, Shank still has an active role in the Phoenix front office. He visits a few days a week to help mentor new faces in the marketing department, just as Colangelo did when Shank first arrived.

Colangelo and Shank have remained close over the years. In the late ‘90s, when Colangelo and his fellow investors purchased a major league expansion franchise that became the Arizona Diamondbacks, Shank and others in the Suns marketing department helped set up many of the baseball team’s initial sponsorships.

After the Diamondbacks won the World Series in 2001, Colangelo called Shank into his office and handed him a championship ring.

“It’s not something I wear – only on special occasions or something,” Shank said.

So Harvey Shank, who pitched just one game in the big leagues, still owns a World Series championship ring. Take that, Moonlight Graham.

“It’s a sparkler,” Shank added.