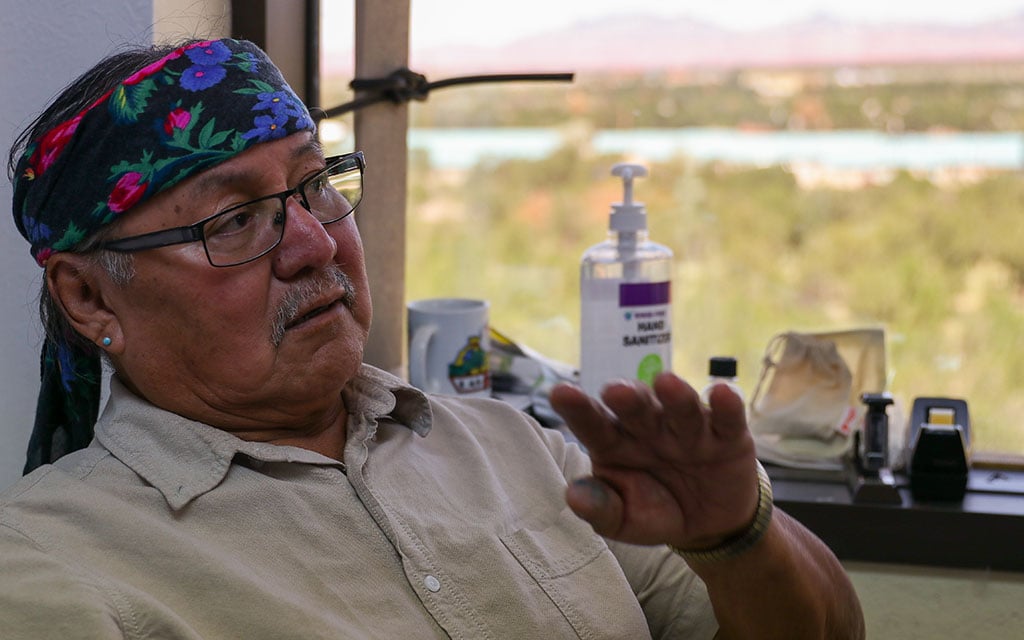

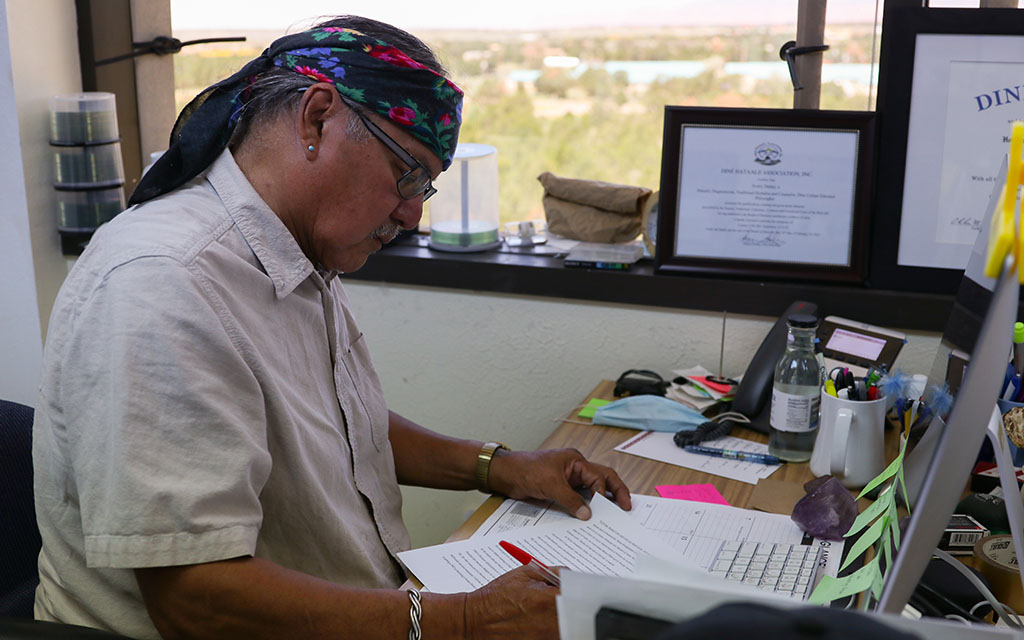

Like Begay, Denny says family and community are central to the process of healing.

“All the religious intolerance and human rights violations and historical trauma – and all the things that happened to our people that got us all sick – the people that have done that to us couldn’t make medicine for us,” he said.

“They didn’t know how to heal it, to heal us.”

Barriers to care

Traditional services are free to Native Americans at facilities operated by the Indian Health Service, but supply can’t always keep up with demand at the chronically underfunded federal agency.

A 2011 federal report found just 33% of 514 IHS and tribal facilities providing mental health services offered traditional healing. And many of those clinics are located on or near reservations, even though 70% of Native Americans live in urban areas.

“Almost all of those services are for reservation-based populations, and for decades, the majority of Native people have not lived on tribal territories,” said Weaver of the University at Buffalo. “So there’s a mismatch between where services are and where people are. Some Native people have private insurance and can pay for mental health care. Many others do not.”

In some states, health officials are trying to address all this.

For years, Arizona, California and other states have been asking the federal government for the OK to reimburse the cost of traditional healing services under Medicaid.

While IHS provides free health care to Native Americans, services are available only to members of federally recognized tribes and within specific geographic service areas.

With over 50% of Native Americans lacking private health insurance, Medicaid becomes another important source of care. As of 2019, federal data show, some 42% of American Indians and Alaska Natives relied on Medicaid or public health insurance coverage.

In 2015, Arizona established a workgroup to help develop parameters and potential payment methodology related to traditional healing for federal and state Medicaid officials to consider.

In a memo a year later, Arizona leaders noted that traditional healing, “while beneficial to tribal members,” has not been considered a covered Medicaid service, “despite it being promoted in the Indian Health Care Improvement Act and by IHS.”

And yet, to date, the federal government has declined to approve reimbursement.

In a letter last month from the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, the federal agency said it “recognizes the state’s goals of addressing disparities in the American Indian and Alaska Native community and will continue to work with the state on this request.”

CMS declined additional comment about why the change has taken so long. It so far has not approved reimbursement for traditional healing for any state. A spokesperson said the requests “are still under review.”

Heidi Capriotti, a spokeswoman for Arizona’s Medicaid agency, said federal officials “recognize our interest in traditional healing services and how important it is for our tribal communities, and have agreed to continue negotiations on this topic.”

“We don’t know a specific issue that’s holding it up, only that they like to align multiple states,” Capriotti said. “So it might be a conversation that includes more than Arizona.”