Carlos, 16, who’s also sheltering at Hospitalidad y Solidaridad, remembered a panic attack that came on after memories surfaced about his escape from Honduras.

“I hadn’t had time to process everything that had happened. Then it hit me, to run away. Not be like a locked up prisoner,” he said. “But now, thank God, I have calmed down.”

Carlos fled Honduras over a fear of extortion related to what he called a misunderstanding between his father and a local gang. After traveling to Tapachula with a 23-year-old cousin, he plans to reunite with family members who already have permanent residency in Mexico.

This wasn’t the first time Carlos dealt with gang threats. A few years ago at school, Carlos said, gangs tried to coerce him into acting as a spy for them. To avoid the pressure, he switched schools.

For Carlos, life was terrifying in Honduras, which he said “has an atmosphere like that of a war.”

After what he went through, Carlos has difficulty trusting people.

“In my opinion, it is better to know people from afar,” he said. “Because in my experience, in my life, I have had quite a few people who have hurt me.”

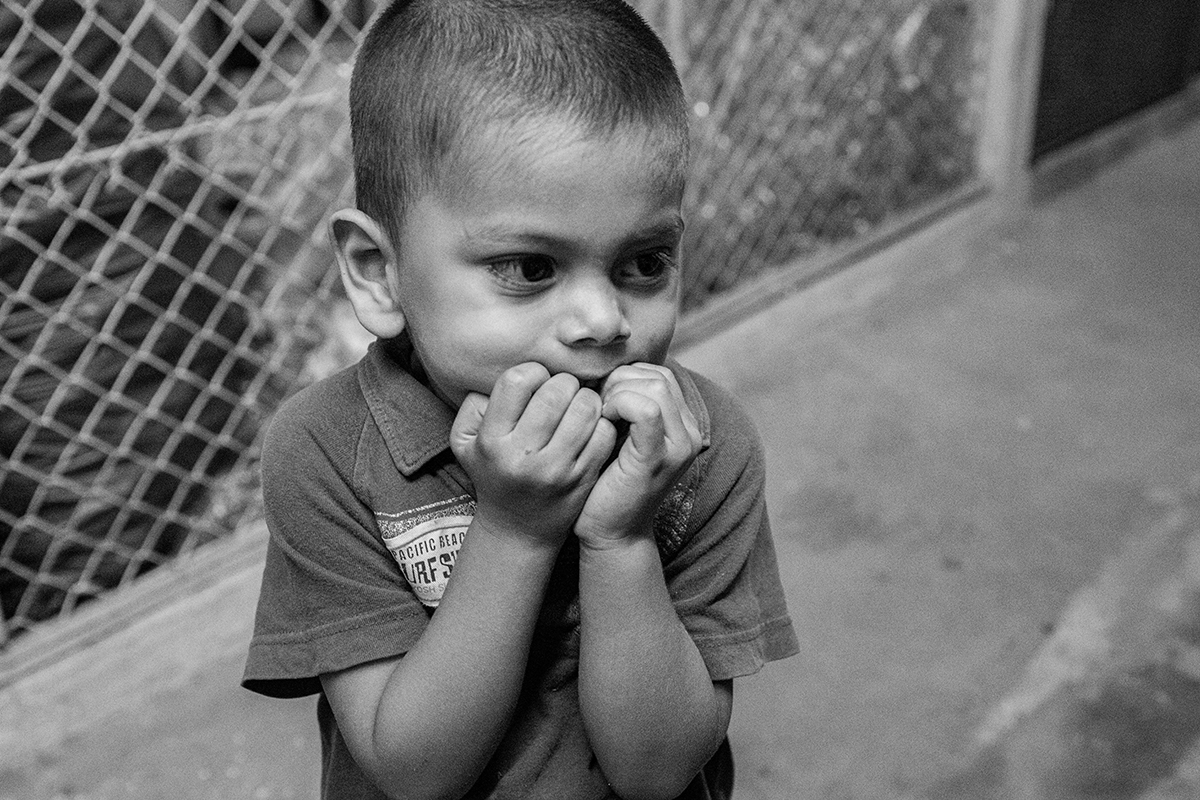

For another Honduran boy, Jose, 14, who had been at Hospitalidad with his family for a few months already, leaving home felt almost surreal.

“It was new.” he said. “I had to get across the border and go through periods of hunger. It feels like I’m on vacation, just that it’s a permanent vacation. Permanent and unexpected, since I’m not going back to my country and I won’t be able to see my friends again.”

Children who have fled have mixed emotions about returning home.

“I miss it in terms of visiting my relatives, but on the other hand I don’t because there’s this fear that something could happen,” Jose said.

Carlos professed no such misgivings.

“If I could return right now, I’d already be there,” he said.

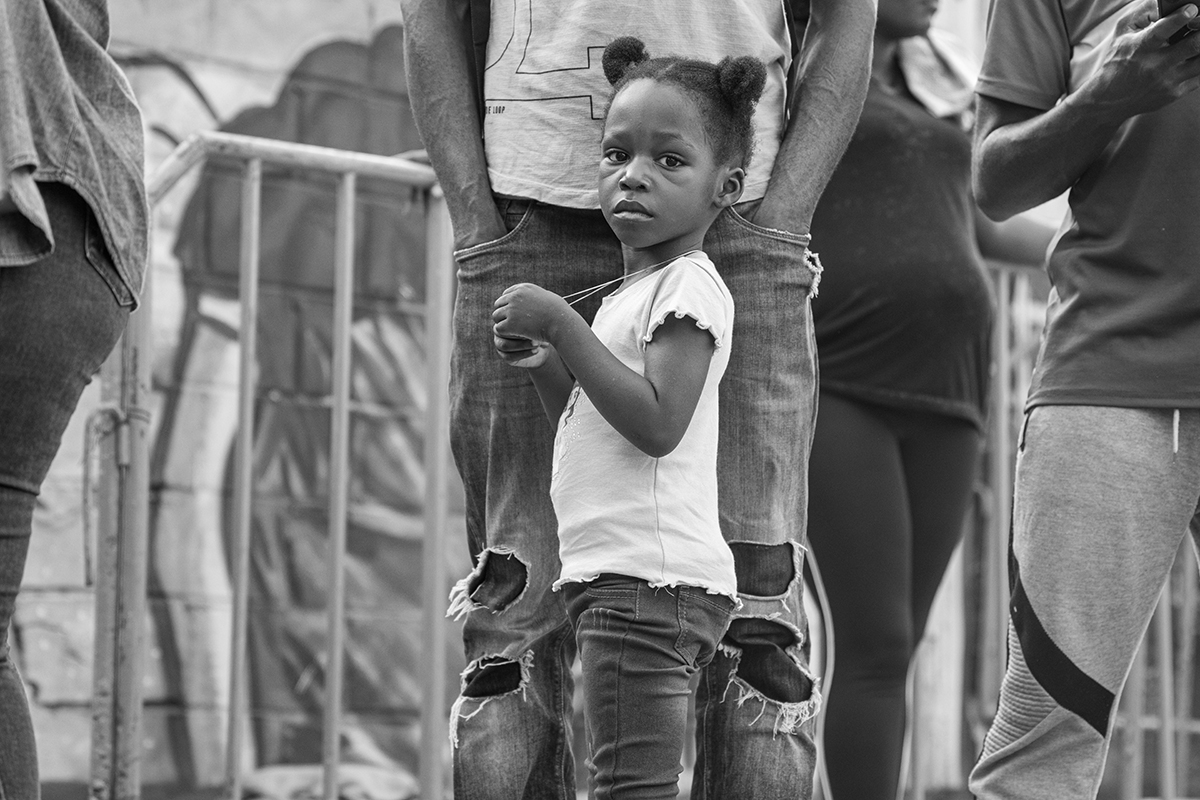

She doesn’t speak

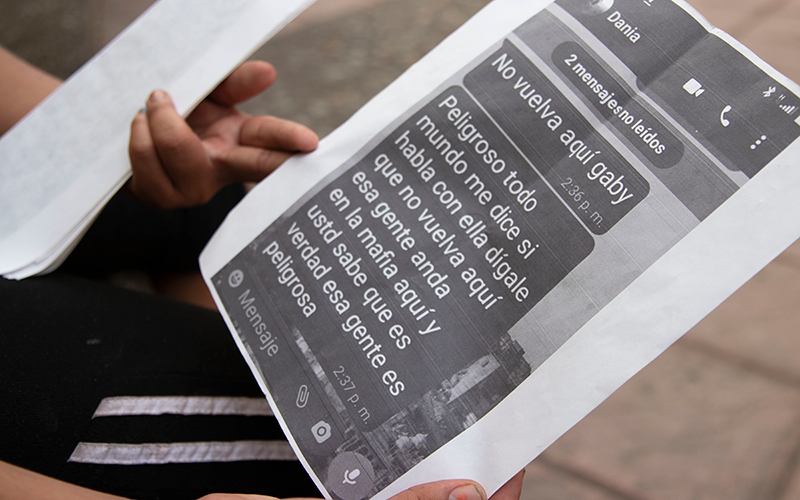

For Vilma, 36, a mother of two from Guatemala who asked that only her first name be used because of safety concerns, the thought of returning home is out of the question. She and her children fled their home in January after a sequence of traumatic events that she said included the rape of her daughter, the robbery of money she had been loaned to sustain her family and a subsequent attempt on her children’s lives after she couldn’t repay the loan.

Vilma said they were forced to live in one room for over a month, defecating in a trash bin and unable to step onto the patio for air because they were being monitored by their would-be assassin. Her children still get scared when they hear a motorcycle or car whiz by.

Violence is pervasive on the journey, with sexual violence particularly common among women and girls. Experts say most of the women and girls migrating through Mexico have experienced sexual abuse and violence since childhood. In many cases, they normalize incessant gender-based violence as a coping mechanism. Latin American countries make up more than half the 25 countries with the highest rates of femicide in the world, according to the United Nations. Only 2% of gender-related killings are ever prosecuted.

Vilma’s 13-year-old daughter stared blankly ahead as she waited near her mother. She doesn’t like to talk anymore, Vilma said. Not after the rape.

“She’s quieter,” Vilma said. “She remembers what happened in our country and she doesn’t like to talk about it.”

Still, being in Mexico has improved things for her kids – at least a little.

“My children felt calmer when we entered Mexico because they know that their lives are in danger in our country,” Vilma said. “Arriving here, they’re already a bit calmer. Not 100%, but they’re a little calmer. We can go out in public.”

If I go back, they’ll kill me

Unlike Vilma’s two children, many young migrants do not have the support of family to help them escape. Half of all child migrants in Mexican shelters are traveling without parents, one of the highest recorded proportions in Mexico, a UNICEF report said.

The statistics are pegged against them: Amnesty International reported that in 2019, 9 out of 10 unaccompanied youth from Central America that came into contact with Mexican authorities were deported. As of June 2021, Mexican authorities had reported deporting half of all Central American unaccompanied child migrants in their custody.