“I’m constructing with the idea that this place will have more space for women and children,” Bermudez said. “It’s been days since I started it, but the funds ran out and that’s where it’s stopped.”

He estimates that the shelter, which primarily relies on donations, will need 150,000 to 200,000 pesos – about $7,500 to $10,000 – to finish a second floor.

“Sometimes we arrive at the point where we don’t have enough (money) for the flour to make the tortillas for the people,” he said.

The water well they rely on is running dry and water needs to be rationed. Propane is expensive, so guests use firewood to cook food in an open-air kitchen near the back of the shelter.

Bermudez wants to add a mini hospital to provide better medical care.

“But they’re only plans, right, because money first. That’s the most important,” he said. “It would be a dream come true.”

Two medics are available full time Monday through Friday to address health needs. For education, Buen Pastor offers two-hour classes three days a week.

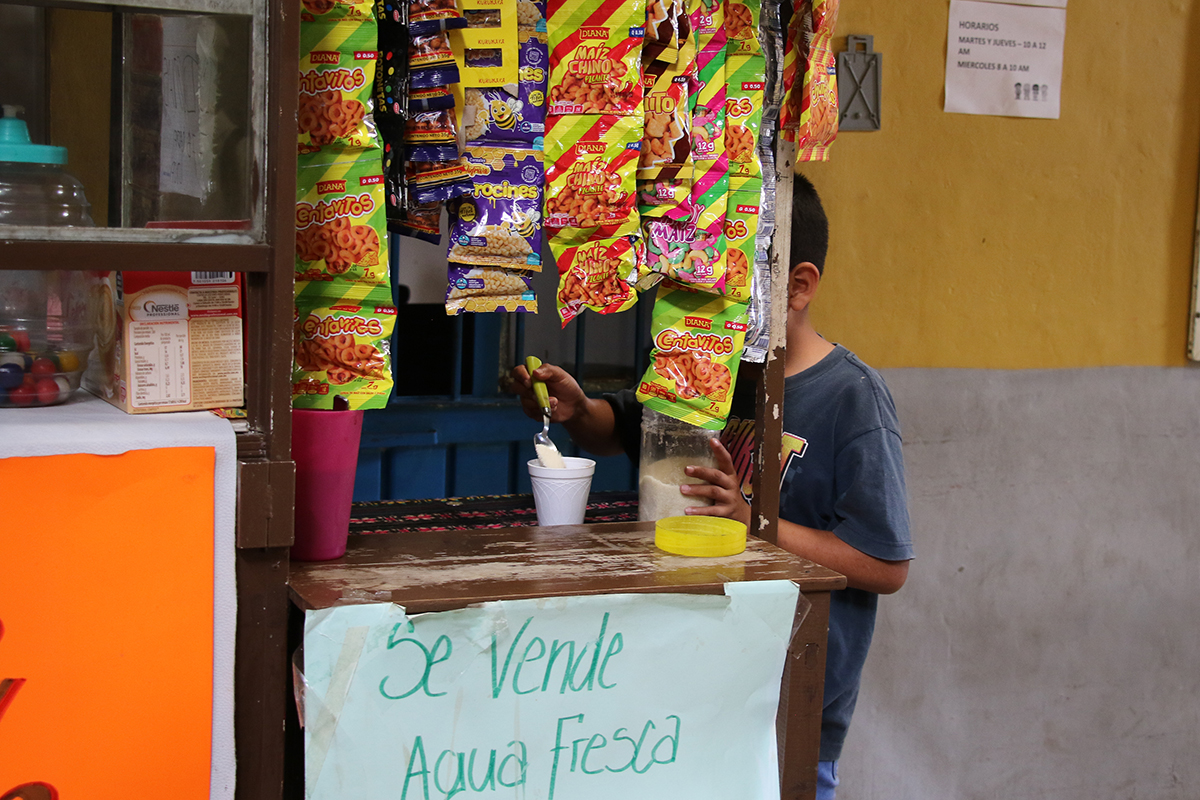

Migrants who previously stayed there complained about the crowding and poor food. They also objected to being expected to buy goods from the on-site store, which made no sense for those without money or work permits.

The Escobar-Rivas family from Honduras stayed at Jesús el Buen Pastor their first three nights in Tapachula. They stay at Parque Bicentenario now.

Juan José Escobar, 43, said the family left the shelter because of questions about their kids’ safety there. He and his wife, Kenia Rivas, 33, have four children, ages 4, 6, 8 and 10. They motivate him to keep living in the park and to patiently wait for their paperwork to be processed.

“It’s for the children. For oneself, you cannot, you’re too old,” Escobar said. “But you make the effort so that they have – that they will experience other new things tomorrow. So that they can have a good education to move forward. That’s why you do it. Because, more than anything, it’s for the children.”

Hospitalidad y Solidaridad, A.C.

On the road toward the airport, about a 10-minute car ride south of town, lies Hospitalidad y Solidaridad A.C., the newest shelter for migrants in Tapachula.

Accel Emadiel Ruiz Mencias, 18, from Honduras, was staying at Hospitalidad y Solidaridad with his mother, siblings and aunt.

“It’s very comfortable to be here. The beds are also good,” said Ruiz Mencias, leaning against a plastic chair with his legs spread out and his hands folded between. His feet were halfway into faded black Puma slides.

He said his family fled Honduras after gang members threatened them multiple times, including dumping a corpse at their home.

Since arriving in Tapachula, they have lived in multiple spaces in the eight months: first on the streets, one night at the main immigration detention center, a stint at Jesús el Buen Pastor and a month in a rented house, thanks to aid from UNHCR.

Now they’re at Hospitalidad y Solidaridad, which has a capacity of 300, with separate housing for men, women and children, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. Most remain about 45 days, but some have stayed as long as six months. Migrants must be actively seeking asylum, said Angélica González, head of liaison and advocacy coordination for the shelter.

“It’s calm, and not (just) any person enters,” Ruiz Mencias said.

UNHCR provided the family with a card to help pay for one month’s rent plus food as they awaited the answer to their asylum application. When the card ran out, they asked UNHCR for more help.

“They told us that they couldn’t help us, and there were shelters where we could go to,” Ruiz Mencias said. “So, we thought hard about it and asked around to see which was the best. Because this one is the best. And they told us this one. And well, here is really nice. I like it.”

Guests can come and go as they please, but Ruiz Mencias prefers to stay in.

Each person is assigned to a team that assists with upkeep, which includes cooking, serving food and cleaning the grounds. Ruiz Mencias wakes up at 7 a.m. to clean the men’s restrooms and his own room. After breakfast, the team cleans the school, theater and one other building before lunch. He enjoys having things to do.

He goes to school, which also keeps him happily occupied.

Classes are divided into four age groups, with each group receiving six hours of instruction per week from one instructor.

“When the children leave, we give them a certificate that does not have official validity,” said Fernanda Acevedo, who oversees the general coordination of the shelter. “But it has worked so that when the children leave the shelter, in certain cases the professors call us and (we say) ‘Oh, they took so many hours on this project.’ So, yes, it has helped.”

As of March, Ruiz Mencias and his family’s asylum and residency had been approved. They were planning to leave within a few weeks, but the plans weren’t solidified.

The family never wanted to leave Honduras; they weren’t wealthy but they had enough to live. When they settle in their next place, Ruiz Mencias hopes to go back to school, get a job and help his mom out with the bills.

“Arriving here in Mexico is like starting over from zero. But it’s done. We have to continue now,” he said.