Rep. David Schweikert, R-Fountain Hills, defends his frequent use of special order speeches, typically devoted to fiscal issues, saying they give him an opportunity to “show the math behind the top issues in front of my colleagues and our country.” (Photo courtesy C-SPAN)

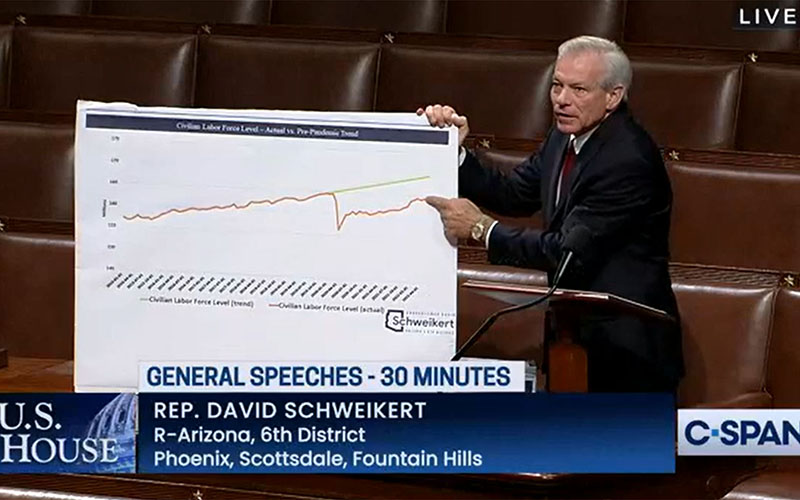

Rep. David Schweikert, R-Fountain Hills, with one of his ever-present fiscal issue charts during House special-order speeches. Schweikert is one of the top users of special order, which gives lawmakers free rein to speak, usually to an empty chamber. (Photo courtesy C-SPAN)

Although he is often speaking to a largely empty House chamber, Rep. David Schweikert, R-Fountain Hills, typically gets animated for the C-SPAN cameras during his regular special order speeches on fiscal issues. (Photo courtesy C-SPAN)

WASHINGTON – Armed with poster boards full of numbers and charts, punching the air for emphasis, his voice rising in indignation, Rep. David Schweikert, R-Fountain Hills, looks every bit the “accountant on steroids” he calls himself.

He’s getting worked up even though he is speaking to a largely empty House chamber on fiscal issues, including gas prices, unemployment, inflation and the federal deficit, and criticizing Democrats’ policies on them.

This is Schweikert’s almost weekly routine during “special order” speeches, that time at the end of each legislative day when the floor is open for two hours of talking. Schweikert talks a lot: He has given a special-order speech 29 times in the current Congress, second only to Rep. Glenn Grothman, R-Wisc., with 38.

“Delivering speeches on the House floor has given me the opportunity to share my work in Congress to folks in Arizona and Americans across the nation,” Schweikert said in a statement about his special-order time. “I consider it a great privilege to present my views and show the math behind the top issues in front of my colleagues and our country.”

It’s not just this session: Schweikert has made 82 special-order speeches since he took office in 2011, becoming a consistent presence on C-SPAN, which carries the speeches and is the largest part of his audience.

Special-order speeches take up four hours each night the House is in session, split evenly between the parties. The first hour for each party tends to be dedicated to leaders speaking on broader topics related to the party’s messaging, said Luke Basham, a Ph.D. student in political science at George Washington University.

Typically, the second hour for each party is broken into 30-minute time slots, where members can speak on any issue they wish. Members have to ask for the time and Basham said they typically are only allowed one special-order slot a week.

If selected, members can speak for as much time as they are allotted, about anything they wish, including topics outside of those being debated in the House. For Schweikert, it’s almost always about finances.

While the members are often almost alone in the chamber, they are joined by potentially thousands of viewers on C-SPAN. The speeches “became a thing once C-SPAN coverage of the House began” in 1979, said Steven Smith, a professor of political science at Washington University in St. Louis, who thinks the speeches are an “exploitation of C-SPAN coverage.”

Smith said the motivation to present these speeches varies by member. Some want to increase eyes on an issue, others want to address a national audience, draw attention to themselves, raise funds for reelection or get a soundbite for social media – sometimes all of the above.

“You do this weekly for quite a long time, you reach quite a few people,” Smith said. “For a member of the House who’s trying to draw attention to themselves for other purposes and maybe running for higher office or simply raising campaign funds, this is a great opportunity.”

Few Americans are spending their evenings watching lawmakers speak on C-SPAN, but Smith said there are still plenty of “political junkies” and others who are watching, which can be “a pretty sizable audience.”

Smith said that over the past 40 years, “virtually every member of the House who has run successfully for the Senate … has surely used special-order speeches as a part of the effort to run for higher office,” Smith said.

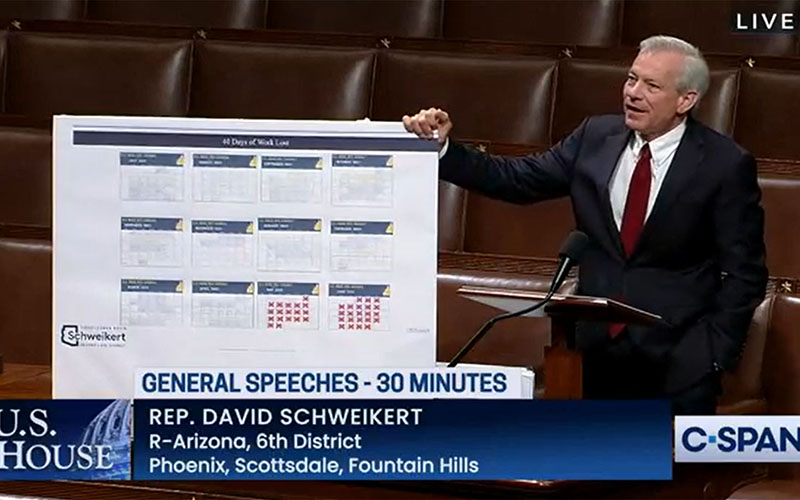

Rep. David Schweikert, R-Fountain Hills, often introduces his many charts and posters during his special order speeches with an apology for geeking out on the numbers. (Photo courtesy C-SPAN)

Special orders may also be used by members who are “more electorally vulnerable,” Basham said. “Basically as a means to increase their visibility (and) be noticed by their constituents at home.”

Schweikert is not looking to move up, but he has faced a couple of tough re-election bids in his Republican-leaning district. He appears to have survived a well-funded challenge Tuesday in the GOP primary from Elijah Norton, who raised $5 million for the campaign. But preliminary results from the Arizona Secretary of State’s office show Schweikert with 43% of the primary vote to Norton’s 33%.

Schweikert, who also fended off a well-funded Democratic challenger in 2020, did not start making recurring appearances in special-order time until the last Congress, when he gave 32 special-order speeches. He gave only 10 in the 115th Congress and just a handful in previous sessions.

“I try to come behind the mic at least every week when we are here,” Schweikert said in a special-order speech on May 19.

For those who speak once a week, like Schweikert, it lets them reach a national audience, which is otherwise difficult to do as a member of the House. It also attracts others who are very “committed to their causes,” Smith said.

Schweikert, the “accountant on steroids,” often nods to the fact that his cause is the government’s financial situation and that he is prone to, as he said, geeking out on the numbers.

“I’ve been here with charts before,” he said during a June 14 special order speech.