“In the early ’50s, it was called Cotton City,” said Lawrence, adding at some points there would be “as many as 100,000 (farmers).”

What brought so many to Eloy was the year-round opportunity to work.

“If you wanted a job, you came here,” Hernandez said. “Once we had cotton, we got potatoes with onions. And if you had a large family that we did and (Ernie) did, too, guess who the workers were and guess who helped finance the living standards?”

Work opportunity is what brought Powell’s family to Eloy as well. His parents traveled from across East Texas in an open bed truck before making it to the desert. “When they stopped in Florence, they had tents,” Powell said. “My mom and dad had a tent and they went through the line and they got one fork, one knife, one spoon, a tin plate and a tin of coffee. And that’s how they started.”

Much like the families of Powell, Hernandez and Lawrence, Eloy was built off migrants and became a hot spot for agriculture with workers coming from California, Mexico and Oklahoma.

Hernandez recalled that his father traveled to Oklahoma with two covered trucks and may have coincidentally brought the Malones to Eloy.

“(He) brought many Negro families to Eloy, where they settled,” Hernandez said. “And they worked in the cotton fields along with the rest of us. I want to say that one of those families that my father brought back, their last name was Malone. No kidding.”

Back then, it was unruly and only the toughest survived. “Even if you were a teacher teaching English, you had to be more physical than your students,” Lawrence said with a chuckle.

Until Eloy established its own council in the 1950s, there was no organized law and it was the last municipality to have martial law applied, Powell said.

“It was a difficult place to live,” he added. “Coolidge, too, all of the smaller towns. You’d have to learn very quickly how to protect yourself.”

Added Sauceda: “They had shootouts here on Main Street.”

Frontier Street had “bar after bar after bar,” and when he was age “14 or 15,” Powell and his cousin got a shoe-shining kit and would shine shoes for tips to make extra money.

“Guys would tip us pretty good-size tips in those days because they were drunk,” he said. “And so we would take that and we went back to our primary residence, and my dad looked at it and said, ‘Where’d you get this money?’ I said, ‘Well, we earned it.’ ‘Well, how’d you earn it?’ ‘Well, we were shining shoes in one of the drinking establishments,’ I said. We were going to be out there again. He said, ‘The hell you are.’ So that was the end of that. We couldn’t go back.”

Eloy was the wild, wild West, where the sheriffs were wary of sending deputies to town, but the disciplinary teachings that Santa Cruz instilled spread into the community. Though the early risings of Eloy were coarse, Lawrence said he “had never seen a bigger thrill and more exciting place to be raised.”

It was a close-knit community where everyone knew nearly everyone by name. When Lawrence’s parents moved from Peoria, Illinois, to Eloy in 1958, they ran the A&W Root Beer stand that his brother-in-law built. Powell said that the stand became the most social gathering place in town and remembered cars would drive around waiting for a spot to open because of limited space.

The busiest street in Eloy was Frontier Street. All outside traffic went through Frontier, which runs parallel to the railroad. However, with the construction of I-10, traffic into Eloy began to slow and the hustle and bustle started to dissipate.

“(My parents) had a brother-in-law that just built the A&W Root Beer stand at 310 West Frontier, which was the main highway from Phoenix to Tucson,” Lawrence said. “And they said the reason they wanted to sell it is because they wanted to retire and it’s too busy. So Mom and Dad thought they struck oil, and they opened it up, and a month later they built I-10 and moved it. They had no traffic except people from the town. You can’t win them all.”

A dynasty in the making

Just off Main Street, Santa Cruz Valley High is home to only 400 students, but the small school is home to big football talent and dreams. (Photo by Andrew Lwowski/Cronkite News)

The football players never spent any time in the weight room, but out in the fields along with everyone else at Santa Cruz.

“But you know, you’d see guys that would leave weighing 150 pounds and come back after a summer pitching melons weighing 175,” Dean said. “By the time they went to two-a-day football practices, that was fun, because working like some of these guys did, they weren’t afraid of it.”

Dean, whose parents moved to Eloy in 1958 and taught, essentially grew up in the high school gym. His father, Howard, spent more than 40 years at Santa Cruz Valley, as a teacher, coach and athletic director.

“We were out there 55 hours a week (in the cotton fields),” Sauceda said. “So when it came time to play football, we were in shape because we walked all day.”

Workers in the field would carry 50- or 100-pound sacks and make 3 cents per pound of clean cotton or a penny and a half for dirty cotton, Sauceda said. The intensive labor it took farming molded the athletes at Santa Cruz to produce a team that struck fear into its opponents.

Back then, Santa Cruz had a “football-loving superintendent” who bolstered the Dust Devils into elite company. “When you’re in a community like Eloy, you want to find out what your strength is and capitalize on it,” Lawrence said. “We had the right managerial team at the school and we were very fortunate.”

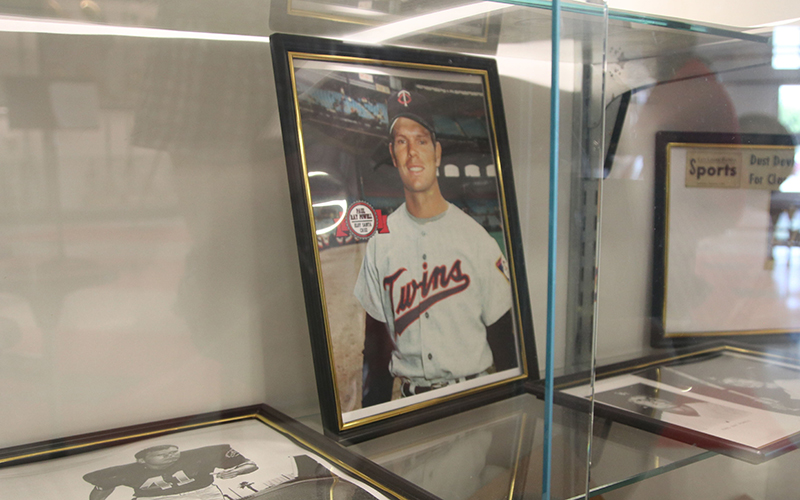

Hernandez said it was gratifying when the Dust Devils won their first state title in 1965. The team was loaded with talent at every position, and it was easy with such players as Art Malone and Paul Ray Powell.

“I mean, we outscored the team by a whole lot of points. Like Paul Ray said, Art (Malone) didn’t play in the second half. Paul Ray played more on defense in the second half because we were playing the other offensive players that needed to play.”