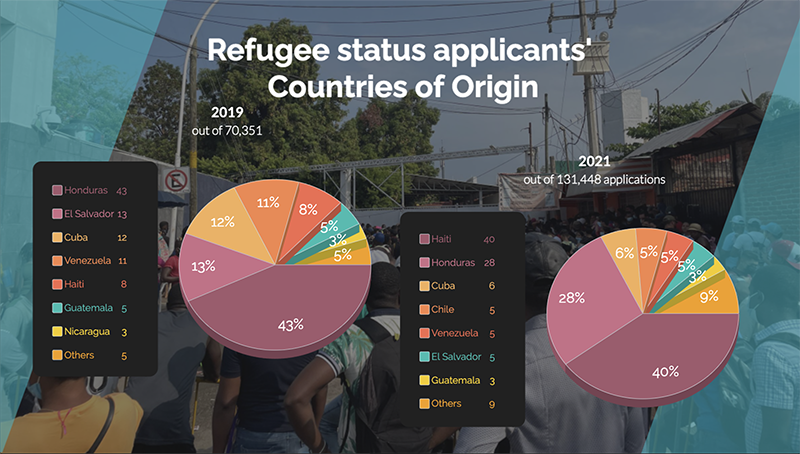

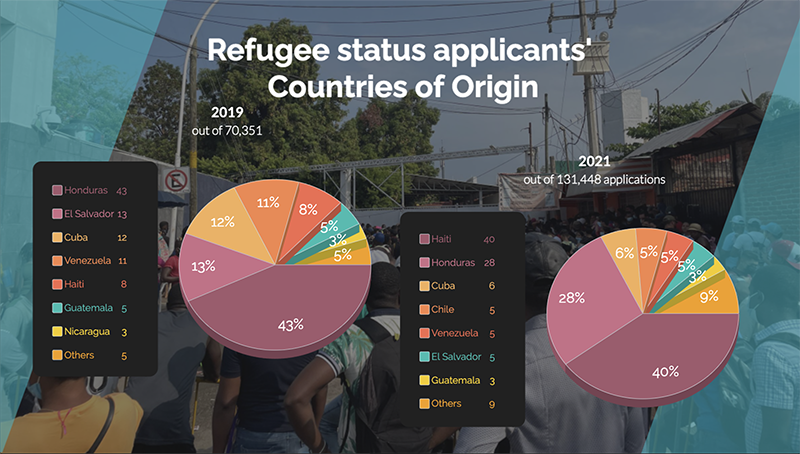

In 2021, Tapachula reported receiving more than 130,000 asylum seekers. The monthly number of refugee-status applications received by COMAR, the Mexican office for refugee assistance, went from about 6,000 in 2019 to almost 11,000 in 2021.

A large number of migrants stuck here are from Haiti. Some left their Caribbean nation recently, but many had worked in Brazil, Colombia, Chile and Venezuela over the past decade. In 2019, COMAR reported that less than 10% of asylum seekers were Haitian. By 2021, 51,000 Haitians were seeking asylum, making up nearly 40% of all such applicants in Mexico.

These charts compare the countries of origin of refugee applicants in 2019 versus 2021. (Graphic by Athena Ankrah/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

All migrants, but especially Haitian migrants, say it has been extremely difficult waiting in Tapachula for weeks, sometimes months, to get permission to stay and work in Mexico or continue to the U.S. or Canada.

“They sell us everything more expensive,” said Freddy, 42, a Haitian migrant who arrived in August 2021. “Even the house, the apartment. The rent is much more expensive because you’re a migrant.”

Freddy is one of two Creole translators working in Tapachula to help others through the Mexican immigration process.

“Most of them, you know, have been here for eight month, one year, so if you have no documents, you are not able to go to school, to get proper health care, you have nothing,” he said. “It’s like they tell you here: You are not a person.”

For parents of young kids, Freddy said, securing a safe place to sleep or even finding their next meal are daily challenges. And enrolling in school isn’t an option until their documents are in order.

“Not even 5% of migrant kids go to school,” Freddy said.

Freddy, one of two Creole translators helping other Haitian migrants in Tapachula, talks with members of the Cronkite Borderland Project on March 8. (Photo by Daisy Gonzalez-Perez/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Haiti has seen more than its share of political and environmental disasters in the past year, including the assassination of Prime Minister Jovenel Moïse and an enormous earthquake, quickly followed by tropical storm Grace. An earlier wave of Haitian migration to South America was spurred by a 2010 earthquake that displaced more than 1.5 million people.

In southern Mexico, Haitian migrants face extreme xenophobia and racism from locals. Many Black immigrants say they face discrimination when looking for jobs, housing and immigration services. They also say Mexican officials help migrants from Spanish-speaking countries navigate the complex immigration system.

Officials in Tapachula defended the government’s treatment of Black migrants. They said the system is simply overwhelmed and lacks resources, including Creole translators.

Last November, the Mexican government held a conference on the mistreatment of migrants, sponsored by COMAR, in which it denounced racism and xenophobia aimed at migrants.

“People in transit have historically faced prejudices and stigmas that have caused the normalization of false beliefs that are an attempt to justify them receiving unequal treatment and injustice,” the commission said in a news release. “Their vulnerable situation increases because of the language and attitudes of xenophobia that they experience in this country.”

The news release said the government, and COMAR specifically, is committed to eradicating stereotypes, prejudices, and stigmas against migrants – through training and education.

In mid-July, COMAR official Cinthia Perez Trejo told Cronkite News in an email there is “no difference in treatment” for migrants seeking refugee status. Perez noted “procedures within the office of the Secretary of Governance of Mexico for sanctioning any public official who commits such acts.”

The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provides legal aid and other resources to some migrants, depending on their vulnerability. That office has said it is adding Creole interpreters, scheduling and facilitating appointments with COMAR, and building a labor integration program to alleviate some of the pressure.