The descendants

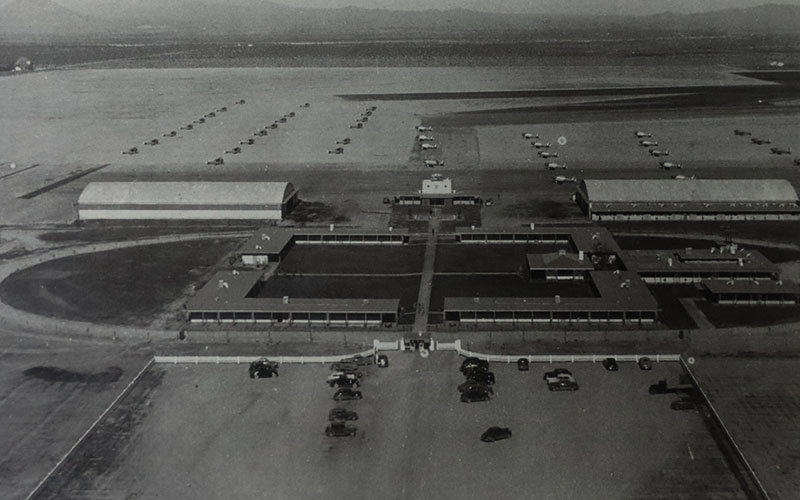

Understanding the experiences of these young pilots is no easy task. The Wings of Flight Foundation has identified 20 who are alive today. Those who have died, or who can no longer tell their stories, live on in the tales of their descendents and at historic places such as No. 4 BFTS.

But their impact is well-known: British pilots who trained in America helped replace the 544 pilots – one-sixth of the air force at the time, according to the Imperial War Museum – who were lost fighting the Luftwaffe in 1940.

Despite such heavy military and civilian losses, the planned invasion of Britain never came. In December, Germany invaded the Soviet Union, opening a costly second front. A year later, America joined Britain, France and the other Allied forces, and after D-day in June 1944, German forces were in steady retreat before surrendering in May 1945.

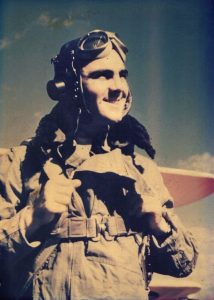

Ken Beeby, who trained at Falcon Field, was first assigned to a bomber squadron. Shortly before the end of the war, however, he was reassigned to a Spitfire squadron – which effectively kept him out of combat. (Photo courtesy of Anne Beeby)

The greater meaning behind the pilots’ sacrifices has not been lost on their descendents, and the personal impact family members have felt from their sacrifices have laid the foundation for much of their own lives.

“Freedom isn’t free. These young men risked their lives for king and country back then – just like those of us that join the military today,” Barber said. “I spent 38 years in the military, and I would not have spent so much time and devoted my life to government service if it wasn’t for the fact of my dad and his buddies and their sacrifices.”

Anne Beeby, Arizona resident and daughter of BFTS pilot Ken R. Beeby, spends her weekends informing people about the history of the flight school.

“It means everything,” she said. “I mean, this is the greatest generation, and people need to know that. So many of them gave their lives, and we are losing them now. They are getting to the end of their lives, and we need to remember what they gave for us – the freedom they were able to obtain for us.”

Ken Beeby resigned his military commission after the war and was back in Arizona by January 1947.

“He loved it here. He loved the weather. It never got too hot for him,” Anne Beeby said.

Dennis Barber, a long-time Ford Motor Co. employee, secured a transfer to a manufacturing plant in California and, shortly after, in Arizona. His infant daughter’s health required a warm and dry climate, and the former pilot knew of only one place that could accommodate.

“Our fathers chose to be Americans,” Barber said. “They weren’t born Americans. They chose to be Americans because of all the freedoms we have in this country that we need to hold so dearly, and unless people are willing to serve, we are one generation away from losing our freedoms.”