When COVID-19 began to spread last year, Thornson quickly made adjustments to prevent the chaos some other funeral homes experienced and alleviate delays in services.

And although Peace Chapel never experienced bodies piling up, as other homes did, Thornson had to expand his operation nonetheless. He bought a larger refrigeration cell and, last August, hired two more people to run the office while he focused on the embalming process. Funeral services and visitations also had to be scaled down to help prevent spread of the virus.

For months, the whiteboard used for scheduling body preparation and services was so crowded that Post-it notes had to be attached to the sides. The phones screaming for attention were a constant reminder of the loss inflicted by COVID-19.

Thornson stresses that his isn’t the only business under such pressure.

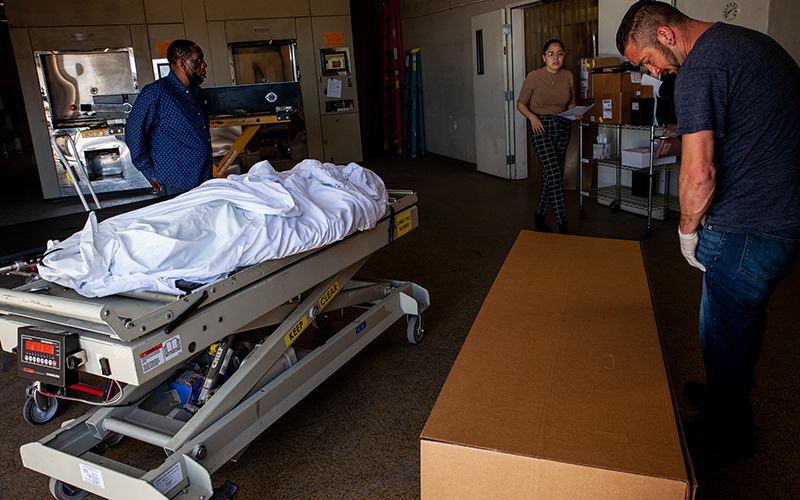

Sean Russo, a cremationist at the Cremation Center of Arizona in southwest Phoenix, said the facility was so overwhelmed there was no space left in the two, large on-site refrigerators. At the height of the pandemic, he worked up to 30 hours of overtime a week. Only recently have things slowed down.

Some mortuaries – engulfed in death and fearful that COVID-19 could be transmitted by a deceased person – stopped embalming. The CDC eventually released guidelines for mortuary workers and said there was little risk of getting COVID from someone who’d died.

Either way, turning families away was something Thornson never considered. Wearing full personal protective equipment, Thornson committed himself to treat COVID-19 cases with the same amount of care and respect as he does all others.

“I constantly feared for my safety and the staff’s safety,” he said, but added that the “families needed closure.”