Diné College wasn’t Harley Interpreter’s first choice for higher education. During summers in high school, at the urging of her elders, she would travel off the Navajo Nation reservation to see what colleges elsewhere had to offer.

But the convenience of Diné College — the first accredited college to be tribally controlled — and its proximity to Interpreter’s home near Tsaile was too good to pass up.

And the longer she attends, her choice makes more sense. As a young Navajo woman, she found the traditional knowledge and language the college offered was invaluable. She helps care for her grandparents who speak Navajo better than English. Earning her degree from Diné College would mean a closer relationship with them and an opportunity to keep their wisdom, language and culture alive.

“The way that we were being taught with our Navajo philosophies was where I really began to learn,” Interpreter said.

It also put her on the front lines of her tribe’s battle against COVID-19, which has already claimed more than 1,200 Diné lives.

When Interpreter’s household – herself, her mother and her grandparents – contracted COVID-19 in December, the college senior stopped working and switched to part-time classes to care for her family. Her grandparents, who were on oxygen concentrators at one point to help them breathe, have since recovered.

Interpreter not only is a caretaker for her grandparents, but also for the culture and the language they carry in their minds and hearts.

“When I came here, it was definitely very different from the way I’ve seen a bunch of other colleges do things,” Interpreter said.

She was raised hearing stories of her cultural background, and her grandparents spoke only Navajo, so the subject matter at Diné wasn’t shocking for her, but she was struck by the focus on community and Indigenous philosophies.

Latrinda Tohe feels the same way.

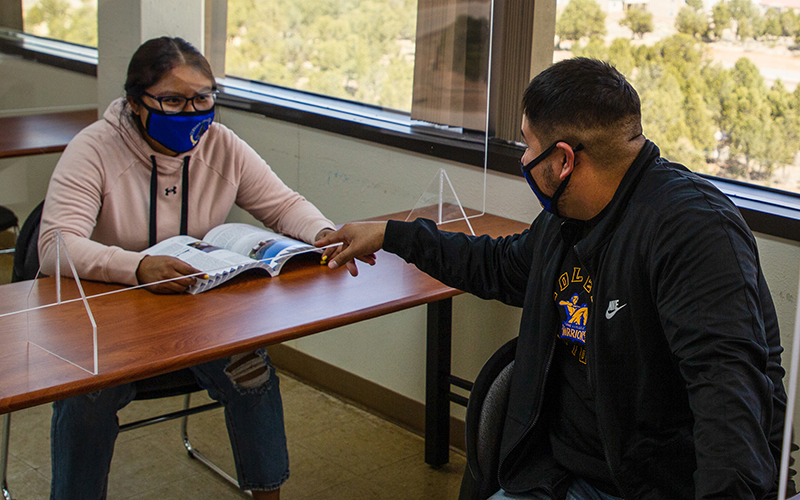

“I chose to come to Diné College because it’s closer to home, and I feel like everyone on the reservation is family,” Tohe said. “The traditions we grew up with, we can learn more about” here.