Tina Acosta, 56, who works for the Oracle Fire District, first heard about the movement on the radio, before COVID-19. Once she saw the impact of the pandemic on her neighbors, she shared the idea with others, including Stiltner, who “took the ball and ran with it.”

The community center provided a space and has done most of the work filling and maintaining the pantry.

“We have homeless just like every community, or people who may have a roof over their heads but they still need help,” Acosta said. “I just hope that it catches on, because it’s such a great resource. It’s not any one particular organization or affiliation. It’s just people trying to help people.”

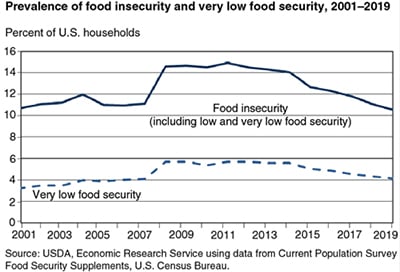

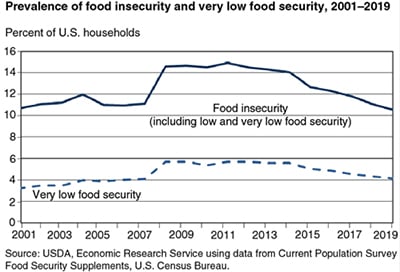

Before the pandemic was declared last March, food insecurity across the country had fallen to its lowest levels in 20 years, according to Feeding America, the largest hunger-relief organization in the United States. But COVID-19 likely reversed those gains.

Prevalence of food insecurity and very low food security, 2001-2019. (Graphic by USDA)

The organization projects that more than 50 million people – 17 million of them children – experienced food insecurity in 2020. In 2019, the numbers were 35 million and 11 million.

Food insecurity occurs when people can’t access enough nutritious food to live active, healthy lives. It can be found in big cities and small towns alike.

Oracle is in Pinal County, which is projected to see a 27% spike in the number of food-insecure residents from 2018 to 2020, an increase of almost 15,000 people, according to Feeding America. Across Arizona, 260,000 people were considered food insecure last year, an increase of 28% from 2018.

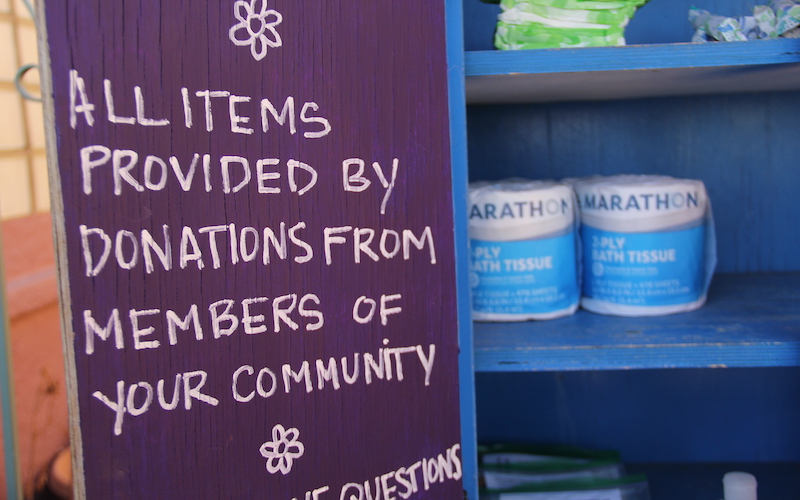

Community members had a big part in building the Oracle Pantry. The Fire District donated the lockers, which had been sitting in storage, and local artists decorated them. Volunteer handymen built a roof to protect the lockers during hot summers. And once javelina started figuring out how to get food from the bottom row of lockers, food products were moved to the top row to keep the critters out.

Donations for the pantry also are community-driven. At first, Acosta and the center staff kept the lockers filled. Over time, other residents started contributing, even adding such items as handmade beanies to keep heads warm during winter.

To restock the pantry, the center periodically holds Fill the Truck drives, such as the one planned Saturday at the Dollar General in Oracle.