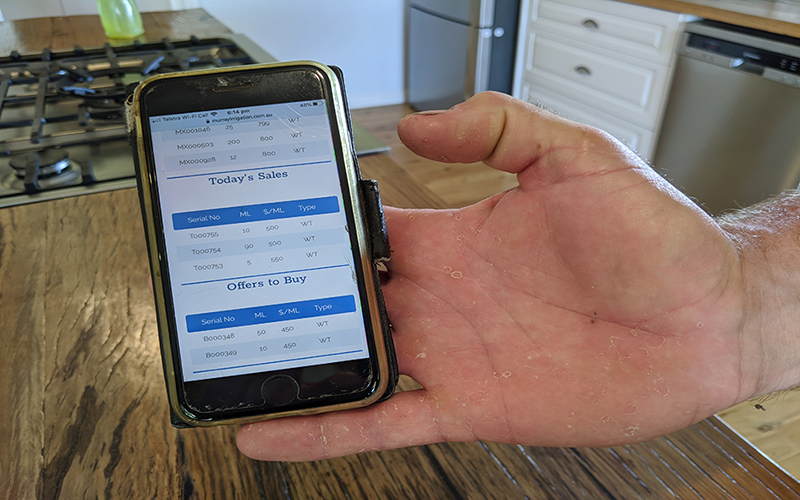

For Carly Marriott, whose family farms wheat in southeastern Australia, selling water is as easy as selling a couch on Craigslist.

“Here’s our account,” she said, opening a website on her smartphone. “We want to sell 85 megaliters, and we put a price on it of $600.”

In some ways, the website is better than Craigslist, because it takes out the guesswork. It tells you how much your “couches” actually are selling for right now. There are also several smartphone apps that, as one app puts it, make checking water prices “as easy as checking the weather.”

Setting a price isn’t hard, she said. “You just look at everyone else and what they’re doing.”

Marriott usually grows wheat on her land near Barooga. But when water is scarce, it becomes expensive, and that means it’s not worth it for them to buy enough to sow wheat.

“Water at the price it’s at, we can’t make money off it,” she said last February. “So we sell it.”

It’s a market. And that’s an idea that leaders in some Western U.S. watersheds are eyeing, with proponents saying that, as the New York Times has reported, “water is underpriced and consequently overused.” Australia, meanwhile, has had just such a system for years – revealing the tradeoffs involved.

The water Marriott is selling about comes from the Murray-Darling River Basin in southeastern Australia, and it’s said to be strikingly similar to the Colorado River Basin across America’s Southwest: dry landscapes that are getting drier, great variability from year to year, and a long history of farming despite the arid conditions.

Mike Young, who studies water policy at the University of Adelaide, said users in the Colorado River Basin are missing out on an opportunity to double or even triple the value of water, to keep it from being wasted and ensure it’s put to its highest use.

“It’s not rocket science,” Young said. It boils down to making it easier to buy and sell water.

“In the U.S., a water right is very much like a title to land, and it’s very hard to move from one location to another.”

In the Murray-Darling, water rights are more like currency – or shares in a company – than they are a family heirloom.

“That enables us to manage droughts much more effectively,” Young said. “We don’t need drought management plans, it’s all worked out.”

Young doesn’t think the system is perfect, but in the world of water, he said, the U.S. system is like a Model T Ford while Australia has a Cadillac – maybe even a Tesla.

“The challenge for America is for somebody to build such a system so you can actually look across the fence and say, ‘Gee, I’d love one of those,’” Young said.

One Nevada ranching community is trying to turn their Model T into a Tesla by borrowing elements of the Australian system.

Jake Tibbitts is the natural resources manager for Eureka County, Nevada. It’s an area known as Diamond Valley, and he said it has a reputation as a “poster child for water mismanagement.”

“There’s way more water rights than there’s water available on a sustained basis,” he said.

There’s about 30,000 acre feet of water that’s consistently available each year in an underground aquifer. But there’s more than four times that amount on the books that people have a right to use.

“The status quo is something we just don’t feel we can live with,” Tibbitts said.

When valley residents convened in 2015 to talk about what to do, Young, the water-policy researcher from Australia, addressed them.

“I really thought maybe he’d be poo-pooed, and folks would move on to something else,” Tibbitts said. “But there was a lot of interest by those in attendance at that meeting and some of the concepts.”

Farmer Carly Marriott stands by Australia’s Mulwala Canal, which is considered the longest irrigation canal in the southern hemisphere, in February. “It was a great engineering feat in its time,” Marriott said. “Our families all built it and have farmed off of it accordingly, and now government is using this canal to move water directly around the people who finance this system to send it downstream.” (Photo by Rae Ellen Bichell/Mountain West News Bureau)

It was clear, he said, that water users wanted a market. So they came up with a plan: They would ditch the use-it-or-lose-it setup, where people actually get punished for conserving water, and instead create incentives to save water.

“If they don’t use the water, they can sell it to somebody else, they can move it to another piece of ground that they may have or they can bank it,” Tibbitts said. “So in good years, water they don’t use, they can put into the water bank. And then in subsequent years, they can withdraw on that water that they banked when they have a water shortage.”

It wouldn’t be exactly like Australia – water would still be tied to a water right on a specific piece of land and part of that land’s deed. Transactions would take place on paper, not on a smartphone. And water would not be allowed to be moved out of Diamond Valley. But it would be a market – they hope, anyway – where private parties work out an agreement about trading and submit a form to the state engineer to move water from one account to another. Tibbitts said it would be way faster and cheaper than water trading now.

But even if the Diamond Valley manages to pull off this overhaul, it might not be the silver bullet against water worries. Erin O’Donnell, a water law and policy specialist at the University of Melbourne, said the story with Australia’s water market is complicated. The major overhaul happened 17 years ago.

“That was 2004, in the early stages of what we came to know as the Millennium Drought,” she said.

The government spent an “extraordinary” amount of money – about $13 billion – to buy water for the environment, to keep waterways healthy, O’Donnell said. The rights to use the rest were up for grabs.

“The right to own water and the physical amount of water became highly tradable,” she said, “but there wasn’t a lot of trade until 2007.”

That’s when people really started to panic. The drought was extreme. Irrigators were panic-buying water like toilet paper in 2020. Suddenly, the water market was in action, big time. O’Donnell said state and federal governments alike thought this was good – the water would move to where it was most needed.

Say you’re a rice farmer. Just sell your water this year to someone who needs it to keep their trees alive, like an almond grower. The idea, O’Donnell said, was that they’d get the water they need, the rice farmer would get an income source and most people would stay in business.

“And actually, by and large, that worked out remarkably well for that drought,” she said.

Although water supplies dropped dramatically, she said, agricultural production only dropped a little. That’s the good part.

“But then the drought broke,” she said.

Water became dirt-cheap, and a lot of people saw an opportunity. They started planting very thirsty crops, such as almonds and pistachios. New businesses popped up like stock fund managers for water. The game changed because water became an easily tradable commodity, and people found ways to make money from it.

O’Donnell said all that is leading to widespread “angst and unhappiness” in places like Barooga, where Carly Marriott lives.

Marriott said farmers, including some friends, just can’t compete.

“They’ve had to sell the cows, her husband’s battling depression, her sons can’t come back and farm,” Marriott said. “It’s eating everyone up.”

On top of that, they’re worried about deep-pocketed investors, such as a Canadian pension fund that made the news last year as one of the top owners of water in the Murray-Darling Basin.

So far, O’Donnell said, there’s no evidence big investors are driving prices; instead, there’s evidence that water scarcity and the shift to higher value crops is behind it. Still, it’s jarring to someone who’s on the ground producing food for the country.

“You feel like you’re just defeated by the enormity of it and the complexity of it,” Marriott said. “And it really shouldn’t be that hard.”

In recent years, priced-out farmers have gotten angry at not being able to afford any water, angry enough to throw an effigy of the water minister, the official who oversees the market, into the river in a well-publicized event.

“We grow 40% of Australia’s food. Where do you want to grow that?” asked Marriott, who has become a grassroots activist. Her young daughter knows how to chant the former water minister’s name like she’s at a protest.

That brings us back to the U.S. Officials in the Southwest are worried about just such a thing – a farmers’ revolt over any tinkering with frontier-era water law that could make an expansive water market possible. Smaller, contained markets already exist in pockets of the West, such as the Colorado-Big Thompson project on Colorado’s Front Range, where water held in high mountain reservoirs is converted into units and bought and sold by cities and farmers alike.

Dustin Garrick studies natural resource management at the University of Oxford in Great Britain. Australia, he said, revamped its whole system from the top down during a drought crisis, with the federal government coming in to take control of basin planning.

“And it led to a backlash, a political resistance,” Garrick said. “And basically it was a crisis response.”

Recent findings of corrupt behavior by water authorities – not to mention the continued exclusion of Indigenous communities from decision making – haven’t helped smooth those bumps. The Colorado River Basin, on the other hand, has had the luxury of responding to rising temperatures and falling reservoirs more gradually.

“Rather than a sudden crisis, there’s been a steady squeeze, and it’s allowed for a process of adjustment,” Garrick said.

That process, he said, has led to coalition building, innovations and ideas that could mean more lasting progress.

He said the question now is, will that delicate progress hold when the Colorado River Basin encounters the “black swan” disasters that climate change triggers. With its biggest reservoirs likely to hit their lowest points ever in the next year, the Southwest could face that test soon.

In Nevada, Tibbitts and his neighbors are working on just that.

“There will never be 100% consensus,” he said. But he’s confident his community will be able to come to its own tailor-made solution that everyone can live with, even if for some it’s a bitter pill to swallow. The key is giving the locals the power to figure it out.

“That’s a big difference here, as we developed it from the grassroots – from the bottom up – where a majority could sign a petition actually asking the state engineer to impose this on them,” he said. “Local communities have the tools to develop their own solutions that everybody can live with.”

Still, after doing all that, Diamond Valley’s new plan now is clogged in the legal pipeline, awaiting a decision from the Nevada Supreme Court. Tibbitts is watching the clock, because if it doesn’t get unclogged by 2025, the state engineer will be forced to start cutting people off from their water rights. And that, he said, would rip the valley apart.

Reporter Luke Runyon of KUNC contributed to this story.

Support for this story, reported in early 2020, came from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that partners with journalists and newsrooms to support in-depth reporting and education around the globe.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, the O’Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West in Montana, KUNC in Colorado, KUNM in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.