MOAB, Utah – Climate change and increased demand for water across the Southwest are shrinking the Colorado River’s second biggest reservoir, Lake Powell. Although water managers worry about scarcity issues, two local river guides are documenting the changes that come as the enormous reservoir hits historic lows.

For the past three years, Mike DeHoff and Pete Lefebvre have carefully photographed and mapped Cataract Canyon on their guided raft trips on the river. For more than four decades, the lower portion of the beloved canyon has been submerged, but now that the lake’s water levels are plummeting, things in Cataract are rapidly changing.

“There are rapids down there that are not on any published river map right now,” DeHoff said. “They’re coming back at a rate that publication can’t keep up with.”

The pair photograph these returning rapids year-to-year, illustrating in real time what it looks like as Lake Powell’s water levels shift. Lefebvre said he was inspired by “Chasing Ice,” a 2012 film that documented shrinking glaciers from a sustained rise in global temperatures.

“I remember watching that movie and thinking, ‘I need to be doing this in Cataract,’” Lefebvre said. “If I have a picture of Dark Canyon and the mouth of Clearwater (Canyon) and these places where the rapids used to be, maybe I can start documenting that change.”

It wasn’t long before their hunt for new rapids sent them digging into the past. DeHoff has spent hours poring over old river maps, guidebooks, and historic photos in search of clues.

“The great thing about it is it’s a real live treasure hunt and kind of terra incognito every year,” he said.

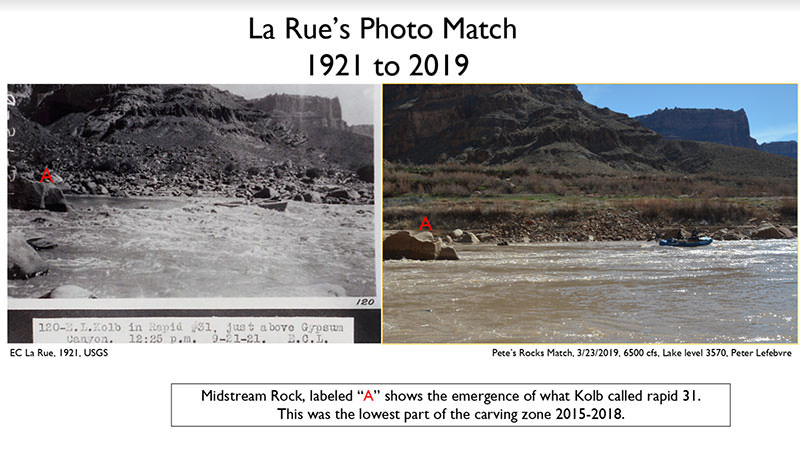

The Returning Rapids project’s first historic photo match was of a 1921 photo taken by federal hydrologist E.C. La Rue near Gypsum Canyon. (Photo courtesy of Returning Rapids of Cataract Canyon)

Their first “eureka moment” came when they correctly matched a 1921 photo from a survey of the Colorado River with one of their own. The picture shows a boat running through a dynamic stretch of Lower Cataract, where the reservoir’s mostly flat water exists today. But Lefebvre said some character now is returning to this stretch of river.

“It started with just like a little ripple in the water to the surface,” Lefebvre said, “and then there was a little burble. And then, oh, there was the tip of a rock sticking out. And then another rock was sticking out, and then eventually you start seeing this thing turn into a riffle,” which is a shallower, faster moving section of a stream.

They named the spot La Rue’s Riffle, for E.C. La Rue, the U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist who took that photo of the boat nearly a century before.

Fed up with the slow rate of guidebooks, the pair recently published their own supplemental river map on their website, Returning Rapids of Cataract Canyon. It lays out the freshest, gnarliest rapids of the lower canyon.

“Initially we were just doing it for us,” DeHoff said. “But people get excited about rapids. And that’s just been this thing that’s been a spark that has caught a lot of people’s attention.”

Cataract Canyon boaters head down Rapid #29, also known as “The Chute,” in high water. (Photo courtesy of Returning Rapids of Cataract Canyon)

Their citizen science work has attracted Colorado River decision makers and researchers like Utah State University professor Jack Schmidt, who runs the Center for Colorado River Studies. Some of Schmidt’s work receives funding from the Walton Family Foundation, which also supports KUNC’s Colorado River reporting project.

“The greatest value of what Mike DeHoff and Pete and others are doing in the Returning Rapids Project is that they’re collecting the basic data that gives people pause, to say, there’s a benefit and a cost to everything we do about the Colorado River,” said Schmidt, who has devoted more than 30 years to studying Colorado River issues. “That benefit or that cost is something we ought to know about before we do it.”

This fall, Schmidt joined other academics and research scientists on a trip through the canyon with DeHoff and Lefebvre. Cataract Canyon is becoming a well-known place to study what happens to an ecosystem when a reservoir recedes and a river has a chance to return to a sense of former wildness.

“We’ve taken some people who are highly trained scientists, and geologists, and whatever out there,” DeHoff said. “And it’s really neat to see their faces where they’re like, ‘I’ve been studying geomorphology for 15 years and here I am out here seeing it right before my eyes, happening faster than I can even believe it’s happening.’”

Whether due to overuse, prolonged drought or political change, researchers are beginning to contemplate a future for a severely diminished Lake Powell. In October, the reservoir dropped to just below 11 million acre-feet of water, about 45% of capacity. With a dry and warm winter forecast for 2021, there’s no relief on the horizon.

Lefebvre said the Returning Rapids project is showing a silver lining to a reduced reservoir. It’s not only about new thrills for rafters – they’re also watching an entire ecosystem shift.

“Instead of this monoculture of weeds and a mud canal … we’re getting all this character back with rapids, beaches, currents, eddies, animal life, and native vegetation,” he said. “And so that’s how I see (Cataract Canyon) recovering. It’s a nicer place to be now.”

Negotiations on a new set of operating guidelines for the Colorado River’s management are set to begin at the end of this year. Who is at the table for those talks is still in flux, but Schmidt said river recreators have been – and will continue to be – powerful players in the Colorado River basin.

“They have the potential to change the debate,” Schmidt said. “And it reminds us that boatmen have a tremendous stake and a tremendous potential influence, because they know and care about the resource so much – and it really needs to be celebrated.”

DeHoff hopes that the Returning Rapids of Cataract Canyon gets people thinking about how natural forces can counter the impact humans have on the environment. His advice? Pay attention to those special places in the world, and then decide which way you want the balance to tip.

This story is part of ongoing coverage of water in the West, produced in partnership with public radio stations KZMU and KUNC, and supported by a grant from the Walton Family Foundation.